Background on Pietro Badoglio

Pietro Badoglio was born 28 September 1871, in Grazzano Monferrato, Piedmont, Italy. In 1892, at the age of 21, he joined the Regio Esercito as an artillery officer. His first command in the field was a low-ranking position during the First Italo-Ethiopian War.

Forty years later, he exercised supreme command of the Italian forces that avenged the humiliating defeat suffered there. Along the way, he’d meet success and failure as a general officer in the First World War. A few years later, he was an early opponent of the Fascist Party as it came to power. However, he soon reinvented himself as its loyal servant.

Pietro Badoglio in 1928. Image: Keystone-FranceGamma-Rapho via Getty Images

A politician-general, he became involved in politics during his early military career. He remained politically active for the duration of his life, a year as Prime Minister representing his peak. Throughout his career, one might say that he never expressed any concrete ideology or beliefs. In spite of this, or perhaps owing to this, he maneuvered ably through a tumultuous historical period. He survived his part in the disaster at Caporetto, and evaded war crimes trials for his use of poison gas in Ethiopia. After enjoying luxurious governorships and high military command under Mussolini, Badoglio was a benefactor of his fall.

Early Military Service

Pietro Badoglio’s first experience on the field came as a junior artillery officer in Ethiopia. He survived the humiliating defeat at Adwa in the Italo-Ethiopian War, in 1896. Decades later, he served in the invasion of Libya during the Italo-Turkish War. A junior officer in both conflicts, he’d return to both theaters as supreme commander in the future.

Pietro Badoglio rose to prominence through his role during the Sixth Battle of the Isonzo. He planned and executed the capture of Monte Sabatino on 6 August 1916, a strategically vital point near Gorizia. Italy held great importance in the city of Gorizia, which was held by Austria but possessed a large Italian minority. As glory and success were rare attributes on the Italian Front, Badoglio’s victory elevated his profile throughout Italy. He later held the command of a corps at the disastrous Battle of Caporetto.

Battle of Caporetto

The burden of fighting both Italy and Russia strained the fragile Austro-Hungarian Empire beyond its capacity. Germany deemed it necessary to intervene in October 1917, resulting in the Battle of Caporetto. The Battle of Caporetto represented an unparalleled disaster for Italy during the First World War. The Regio Esercito suffered over 300,000 casualties, and Austrian forces reached a position from which they could see Venice. Only fierce resistance along the Piave River prevented them from reaching it.

After the battle, Badoglio became a scapegoat for some who held him to blame for Caporetto. A military commission into these charges deemed most unfounded, although his poor dispositions contributed to the defeat. After the battle, Pietro Badoglio became the Chief of Staff to the new commander of the Italian armies, Armando Diaz. In this role, he helped Diaz to rebuild the army after the disaster of Caporetto. While their long preparation for future battles frustrated the Allies, who urgently desired an offensive, the wait paid off. In the battles of 1918, the revitalized Regio Esercito broke the back of their Austrian rivals.

Between the World Wars

In the years after WWI, Badoglio became the Chief of Staff of the Regio Esercito and a Senator. However, his military career saw a brief interruption, owing to the March on Rome and Mussolini’s ascension to power. Pietro Badoglio responded to the March by offering to ‘disperse Mussolini and his rabble with machine gun fire.’ King Vittorio Emanuele l III declined the offer and instead requested that Mussolini form a government. The token opposition offered by Badoglio saw Mussolini make him ambassador to Brazil, a position where he was harmless. However, Badoglio’s resistance soon proved ephemeral. He changed his stance and his newfound support of the fascist regime. Mussolini named him chief of staff in 1925 and promoted Badoglio to Field Marshal on 25 May 1926. Badoglio then earned a position as Governor of Libya.

Pietro Badoglio

Badoglio’s role as Governor of Libya lasted from 1928 to 1934. There, he prosecuted a brutal war against the rebels in Cyrenaica and Tripolitania. He utilized the burgeoning Regia Aeronautica and irregular land forces, the blackshirt militia and African troops. Air units would strafe the rebels or bomb them with poison gas and high explosive, in addition to their use as scouts. Where rebel forces were found, they would lead the infantry to pursue and destroy them. While the coast was quickly pacified, campaigns in the hinterlands lasted until 1931. After killing the leader of the rebellion, Badoglio proclaimed peace in Libya. The cost of the peace was 230,000 Libyan lives, owing to a combination of disease, famine, and military policy.

Badoglio (center) and Omar Muktar (2nd from left) after a negotiated compromise with the Senusite rebellion in Libya (1929).

Invasion of Abyssinia

Come 1935, Italy was at war with Ethiopia once again. Emilio de Bono was initially commander of the invasion, but he was found too slow by Mussolini. Badoglio managed to secure the position for himself through his high esteem in the public and his connection to Mussolini. His invasion of Ethiopia opened in January 1936, with the First Battle of Tembien. Owing to Italian superiority in modern weaponry and employment of poison gas.

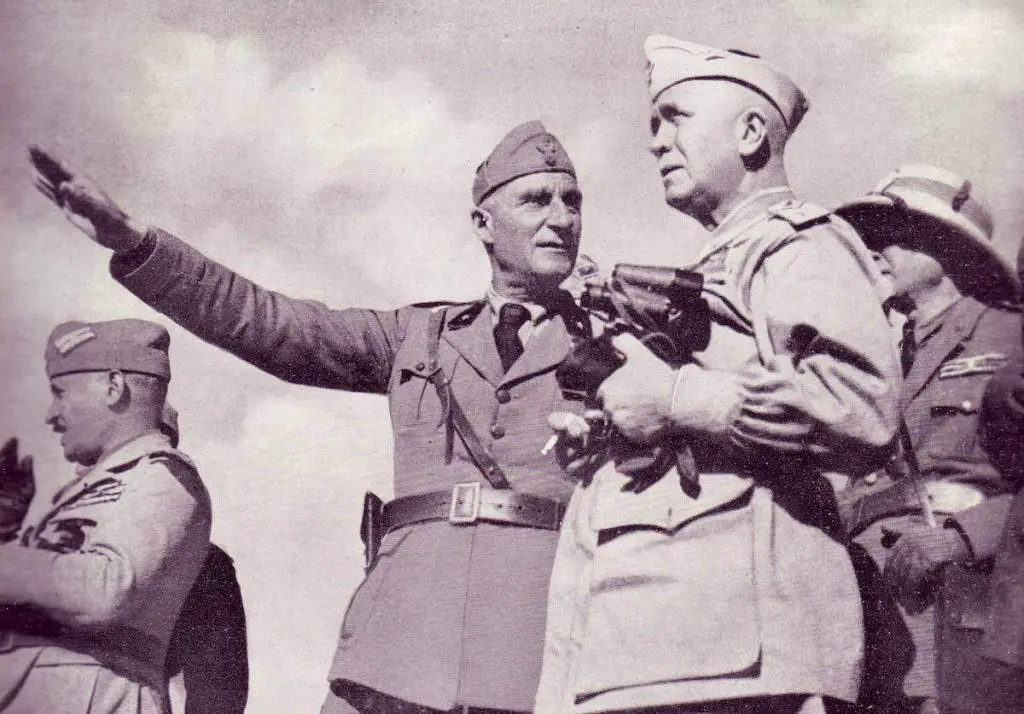

Badoglio during the campaign in Abyssinia.

The Italians suffered 1,082 casualties, while the Ethiopian forces lost 8,000 men. The war took a recurrent pattern from this point on, interrupted only by Ethiopian counter-attacks. The Regia Aeronautica utilized poison gas and bombs to inflict casualties and weaken the Ethiopian will to fight. Then, the Regio Esercito would use their artillery and other modern weaponry to destroy the weakened Ethiopian armies. By the 5th of May, Ethiopian resistance had collapsed. In a show of force termed ‘The March of Iron Will,’ an Italian mechanized column seized Addis Abeba. Rome proclaimed victory, and Badoglio earned the titles of Viceroy of Ethiopia and Duke of Addis Abeba.

WWII And Beyond

Pietro Badoglio played little part in the planning and execution of WWII by Italian forces. He considered joining the war to be a poor decision which the Italian military was unready for. However, he still executed Mussolini’s orders, leading to the abortive invasions of France and Greece. The failure of his invasion of Greece prompted his replacement with Ugo Cavallero, a longtime rival.

Marshal Pietro Badoglio and General Eisenhower on the Battleship Nelson, 20 October 1943.

When Mussolini was deposed in 1943, King Victor Emmanuele III named Pietro Badoglio the Prime Minister. Italy had secretly signed a treaty agreeing to switch sides and declare war on Germany, as a provision of the Armistice of Cassibile. However, Badoglio hesitated to announce it or to inform the Italian armed forces. Badoglio declared war on Germany on 13 October 1943. The treaty and declaration of war caught most units off guard, rendering them unable to resist as the Germans captured and disarmed them. Badoglio persisted as the Italian head of government for nine months, prior to his replacement by Ivanoe Bonomi.

Pietro Badoglio remained a popular, anti-communist figure in Italy until his death in Grazzano Badoglio, on 1 November 1956.

Newspaper photo of Palmina Badoglio, sister of Pietro Badoglio, kneeling at Badoglio’s death bed. Image credit: Aldo Moiato, Stampa Sera, 2 November 1956.

Additional References:

Italian Colonialism, Ruth Ben-Ghia & Mia Fuller

Air Power and Colonial Control: The Royal Air Force, 1919-1939 By David E. Omissi