You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

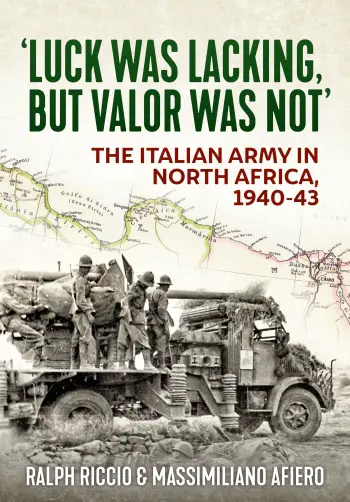

The Italian Army in North Africa, 1940-43: Luck Was Lacking, But Valor Was Not

- Thread starter jwsleser

- Start date

I hope it will be worth all that waiting

For me, it is not whether it is worth waiting for, but whether it has any new information/sources. When I started researching the RE back in the 1980s, I quickly learned to buy anything published in English as information was very scarce. Very hit and miss in quality, but together there is a lot of information.

That is one reason I started to collect the Italian officials. IIRC, I bought the first one on Jugoslavia in 1985. Been collecting them since.

Pista! Jeff

I just received a notice from Helion that this book is now available. They are offering a discount if you order by 20 Feb. If you live in the Uk, the discount is a good deal (free postage). For those in the US, it is about $65 with standard shipping.

The Italian Army in North Africa

I had preordered through Amazon and that cost is currently roughly $62. However, Amazon has not sent an update that the book is shippping and still list a 14 April date.

The Italian Army in North Africa

I had preordered through Amazon and that cost is currently roughly $62. However, Amazon has not sent an update that the book is shippping and still list a 14 April date.

Last edited:

My copy of this book has arrived. Based on my price comparison above, I canceled my preorder and purchased directly from Helion rather than wait for the book to be released in the US. My first flip-through is generally positive but more once I have read the book.

1089maul

Member

Jeff,

Went to my bookshop yesterday. Book which they were getting still not available. As I enrolled with Helion due to your book, I received notification of 20% discount. Order cancelled with book shop and book ordered direct from Helion! However, your comments on the book so far make me think, is it worth it! Regards, Bob

Went to my bookshop yesterday. Book which they were getting still not available. As I enrolled with Helion due to your book, I received notification of 20% discount. Order cancelled with book shop and book ordered direct from Helion! However, your comments on the book so far make me think, is it worth it! Regards, Bob

David Wormell

Member

Looking forward to reading that Jeff!

I was hoping that Riccio and Afiedo’s Luck was Lacking, But Valor was Not would be a refreshing new look at the war in North Africa from the Italian perspective. Certainly a corrective is required to provide a better rounded account of the desert war. I agree with the authors about the way the Italian military is depicted in English accounts of the campaigns in Africa Settentrionale (to give the Italian name for North Africa). I too have observed the same issues with Italian accounts as mentioned by the authors on page XV of the introduction. An Italian focused English account of the campaign is needed, but Luck was Lacking fell short of the mark.

I approach my reviews of new books with two objectives: What does the book offer those that are new to the study of Italy in the war, and what does it offer to those that are quite familiar with the military history of fascist Italy.

To the latter group, this book provides very little new material. Anyone that has read Montanari’s four volume work on Africa Settentrionale (North Africa) will know most of what is in Luck was Lacking. The one bit of new information I learned from the book was a single line on p.141, “[14 February 1942]…and a detachment of tanks from VIII Battalion to Garet Mereim (Segnali Nord) to protect German paratroopers who were laying a minefield.” I had marked it as an error for I thought that no German paratroopers were in North Africa at that time. But I did perform my due diligence and discovered that in fact a battalion of paratroopers was in North Africa in February 1942. I will state that the research was my own as the book provided no assistance, lacking cites/sources in the entire book. This was a significant problem/error given the authors’ intent.

For those new to studying the Italian Army during the war, I have serious concerns. These issues were raised while reading the first chapters of the book. Here the authors addressed a series of stereotypical issues normally mentioned when addressing the problems of the Italian military. The points addressed include the Italian soldier, equipment, supply, the Air Force, and Italo-German relations. In these chapters the author challenge traditional understandings of the problems in these areas. There is nothing wrong with this and it is refreshing to see such challenges. The concern is that the authors present positions, but no arguments or research to support their positions beyond the use of declarative statements. When I read on p.22 that “Italian officers and soldiers in all branches of service performed well, judged by most objective standards.”, this is challenging the research of scholars such as Brian Sullivan, Macgregor Knox, and others. The examples given to support this are merely that Italian soldiers were brave with no objective assessment of training, leadership, tactical skill, etc. In fact, the section on morale (p.24) and leadership (p.27) echo the bravery and loyalty themes without a serious examination of what factors should be used to judge effectiveness in these areas.

Training is raised on pp.30–33. The authors provide an honest assessment of many of the issues. This is a pretty solid section except that they authors down play the importance of the centri di istruzione (training centers) established in 1941 (not 1942 as stated by the authors, see Carrier’s Some Reflections on the Fighting Power of the Italian Army in North Africa).

A chronological presentation of the campaign follows these first chapters. The Battle of Mechili in January 1941 isn’t mentioned. General Babini is mentioned on page 101 but as a clarification to a previous statement that apparently was edited out. Each chapter has an overview followed by quasi detailed discussions of the various battles, but the two parts don’t mesh well. To be fair, the entire North Africa Campaign is covered in 100 pages (pp.102–202). The narratives moves back and forth between an overview of the battles and detailed snippets of specific events, with the overview lacking consistency in the material presented. There are few maps and they are grand overviews that don't support the detailed discussions.

Statements like “The Germans also managed to ‘requisition’ at least a thousand trucks from the Italian high command in North Africa, which meekly submitted to the German request, thus depriving the Italian front-line troops of already scarce transportation assets.” (p.86), or “Piazzoni [commander of the Trieste], however, did not pass on the order and allowed his division to have a leisurely breakfast.” (p.133) without cites or discussion mar the value of the book. I haven’t found a source that discusses the thousand trucks. It is not clear whether these trucks were taken over the three years of fighting or something else. Without addressing the agreements between the two nations and the situation, this statement provides little to understand the war in AS. The Piazzoni issue is more complex as discussed in Montanari (v2, pp.618–619) and Piazzoni might not be the guilty party. There are many more examples of these types of statements by the authors and reflect a possibly unhistoric bias.

One positive is that the book offers many photos I haven’t previously seen. I only found one miss-captioned pictured, but the error was likely by the collector who offer the photo and not the authors. There is a lot of tabular data provided, but much of it is generic and generalizes the many changes in organization and equipment without any specifics.

Overall the book offers little to the specialist. For those new to studying the Italian Army during the war, it introduces many of the problems that beset the army, but the conclusions are suspect at best. The lack of examination/discussion of these problems will leave the reader without an understanding of why history has painted the RE using the brush that it did. I feel the reader will come away with the lesson that history has been unfair to Italy without fully absorbing the flaws of the RE.

I approach my reviews of new books with two objectives: What does the book offer those that are new to the study of Italy in the war, and what does it offer to those that are quite familiar with the military history of fascist Italy.

To the latter group, this book provides very little new material. Anyone that has read Montanari’s four volume work on Africa Settentrionale (North Africa) will know most of what is in Luck was Lacking. The one bit of new information I learned from the book was a single line on p.141, “[14 February 1942]…and a detachment of tanks from VIII Battalion to Garet Mereim (Segnali Nord) to protect German paratroopers who were laying a minefield.” I had marked it as an error for I thought that no German paratroopers were in North Africa at that time. But I did perform my due diligence and discovered that in fact a battalion of paratroopers was in North Africa in February 1942. I will state that the research was my own as the book provided no assistance, lacking cites/sources in the entire book. This was a significant problem/error given the authors’ intent.

For those new to studying the Italian Army during the war, I have serious concerns. These issues were raised while reading the first chapters of the book. Here the authors addressed a series of stereotypical issues normally mentioned when addressing the problems of the Italian military. The points addressed include the Italian soldier, equipment, supply, the Air Force, and Italo-German relations. In these chapters the author challenge traditional understandings of the problems in these areas. There is nothing wrong with this and it is refreshing to see such challenges. The concern is that the authors present positions, but no arguments or research to support their positions beyond the use of declarative statements. When I read on p.22 that “Italian officers and soldiers in all branches of service performed well, judged by most objective standards.”, this is challenging the research of scholars such as Brian Sullivan, Macgregor Knox, and others. The examples given to support this are merely that Italian soldiers were brave with no objective assessment of training, leadership, tactical skill, etc. In fact, the section on morale (p.24) and leadership (p.27) echo the bravery and loyalty themes without a serious examination of what factors should be used to judge effectiveness in these areas.

Training is raised on pp.30–33. The authors provide an honest assessment of many of the issues. This is a pretty solid section except that they authors down play the importance of the centri di istruzione (training centers) established in 1941 (not 1942 as stated by the authors, see Carrier’s Some Reflections on the Fighting Power of the Italian Army in North Africa).

A chronological presentation of the campaign follows these first chapters. The Battle of Mechili in January 1941 isn’t mentioned. General Babini is mentioned on page 101 but as a clarification to a previous statement that apparently was edited out. Each chapter has an overview followed by quasi detailed discussions of the various battles, but the two parts don’t mesh well. To be fair, the entire North Africa Campaign is covered in 100 pages (pp.102–202). The narratives moves back and forth between an overview of the battles and detailed snippets of specific events, with the overview lacking consistency in the material presented. There are few maps and they are grand overviews that don't support the detailed discussions.

Statements like “The Germans also managed to ‘requisition’ at least a thousand trucks from the Italian high command in North Africa, which meekly submitted to the German request, thus depriving the Italian front-line troops of already scarce transportation assets.” (p.86), or “Piazzoni [commander of the Trieste], however, did not pass on the order and allowed his division to have a leisurely breakfast.” (p.133) without cites or discussion mar the value of the book. I haven’t found a source that discusses the thousand trucks. It is not clear whether these trucks were taken over the three years of fighting or something else. Without addressing the agreements between the two nations and the situation, this statement provides little to understand the war in AS. The Piazzoni issue is more complex as discussed in Montanari (v2, pp.618–619) and Piazzoni might not be the guilty party. There are many more examples of these types of statements by the authors and reflect a possibly unhistoric bias.

One positive is that the book offers many photos I haven’t previously seen. I only found one miss-captioned pictured, but the error was likely by the collector who offer the photo and not the authors. There is a lot of tabular data provided, but much of it is generic and generalizes the many changes in organization and equipment without any specifics.

Overall the book offers little to the specialist. For those new to studying the Italian Army during the war, it introduces many of the problems that beset the army, but the conclusions are suspect at best. The lack of examination/discussion of these problems will leave the reader without an understanding of why history has painted the RE using the brush that it did. I feel the reader will come away with the lesson that history has been unfair to Italy without fully absorbing the flaws of the RE.

Last edited:

David Wormell

Member

Thanks Jeff. A great review.