After the September 1943 armistice, the legitimate Italian government fled south and joined the allies. In German-occupied northern Italy, a new German puppet state called the Italian Social Republic formed. This new fascist regime also went by the name Republic of Salò and Repubblica Sociale Italiana (RSI). It would remain in existence from 23 September 1943 to 25 April 1945.

The administrative map of the Italian Social Republic as of 25 September 1943. Image: XrysD / CC BY-SA via www.mapywig.org.

Mussolini’s Rescue

On 12 September 1943, a shattered and depressed Mussolini was liberated by German paratroopers from his prison on the Apennines mountains. Otto Skorzeny, commander of the operation, transferred the Duce into German-held Italian territory and, finally, Germany.

Benito Mussolini with Otto Skorzeny after his rescue from the Campo Imperatore Hotel, 12 September, 1943.

Here he was reunited with his family and brought before Adolf Hitler. Hard questions needed answers. Control of northern Italy was paramount, but Germany did not have the manpower to fight the Allies and maintain civil order. The Fuhrer wanted Mussolini to punish the “traitors” who deposed him in July and re-organize a fascist government in the German-held part of the Italian peninsula.

Birth of the Italian Social Republic

This new entity would manage the civilian administration of the territory, collected taxes, and maintain the German forces stationed in Italy fighting against the allies. Mussolini, who considered his political career to be over, accepted this appointment with little eagerness. Hitler then threatened to transform Italy into another occupation zone, to be deprived of everything, and to be burned down in case of retreat. Mussolini, never able to successfully argue with Hitler, accepted the responsibility of forming the new government.

At 1700 hours on 18 September 1943, a familiar voice cracked the airwaves of Radio Munich:

“Italians, after a long silence, my voice reaches out to you again, and I am sure you recognize it. It is the voice that called you to gather in difficult moments, which celebrated the Fatherland’s triumphal days with you. I delayed addressing you for a few days because following a period of moral isolation; it became necessary for me to regain contact with the world.”

The radio broadcast from Munich aired Mussolini’s speech denouncing the King Vittorio Emanuele III‘s betrayal. He announced the birth of the new fascist state. The government officially formed on 23 September 1943, under the name of Repubblica Sociale Italiana.

International Recognition

Nations that recognized the Italian Social Republic as an independent state include Germany, Bulgaria, Slovakia, Croatia, Romania, Hungary, Japan, Denmark, Thailand, and Manchuria. Curiously, Spain did not recognize this new regime. This new republic existed for only 20 months.

Administration of the RSI

The Italian Social Republic placed its de facto capital in Salò, on Lake Garda’s north-western shore. However, most of its administrative buildings lay scattered in the northern regions. The new state government gathered for the first time in Rocca delle Caminate, near Forlì, on 27 September 1943.

RSI Ministers

Supporting Mussolini as Head of State included the following Ministers:

- Alessandro Pavolini: Party Secretary

- General Rodolfo Graziani: Minister of Defense

- Renato Ricci: Commander of the Militia

- Guido Buffarini-Guidi: Interior Minister

- Francesco Maria Barracu: Undersecretary to the Presidency of the Council of Ministers of the Italian Social Republic

This party adopted a pseudo-revolutionary, subversive, anti-bourgeois, and populist ideology of early fascism. It initiated, but never succeeded in nationalizing companies employing 100 workers or more.

Mussolini (L), Pavolini (C) and F. Barracu (R) on 25 April 1945 in Milan. Three days before Mussolini’s execution.

In the months following his new appointment, Mussolini realized the RSI received similar treatment as other German-occupied countries. Northern Italy was to support the German war effort. The Repubblica Sociale Italiana, including its economic output and human capital, was nothing more than a puppet state. Nazi Germany drained and exploited all its available equipment and materials with disregard.

German counselors flanked Mussolini, and he received protection from 30 SS men. After complaints by Mussolini, Italian troops finally obtained authorization to protect Mussolini to the same degree as the SS detachment.

Mussolini also demanded the release of Italian military prisoners, but Hitler only counter-offered with their better treatment.

A Heavy-Handed Government

Mussolini always pushed for more autonomy but received very little. He also could not control the temperament and actions of the various fascist leaders of the Republic. They showed a new degree of fanatism and violence unseen during the previous 20 years.

The fascist leaders of the RSI showed a strong desire to punish the “traitors,” monarchists, and anti-Germans. They must be held responsible for the military defeats and the demise of fascist Italy. This hate, combined with the ongoing war, sparked an Italian civil war pitting Italians against Italians. This civil war lasted from September 1943 until 25 April 1945.

The majority of the civilian population under the RSI lived in a constant state of terror. This fear subsequently led to progressively filling the ranks of the resistance fighters.

Council of Ministers Tribunal

On 8 January 1944, a tribunal convened that was authorized by the Council of Ministers on 13 October 1943. The Tribunal included former Italian Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano, Field Marshal Emilio de Bono, Giovanni Marinelli, Tullio Cianetti, Carlo Pareschi, and Luciano Gottardi. The defendants explained their vote of no confidence for Mussolini during the Grand Council meeting on 25 July 1943.

Ciano (R) looking back at the firing squad moments before his execution.

The defendants declared that they did not intend to diminish Mussolini’s role, only to give the King authority over the military. The Tribunal concluded on 10 January 1944 with the sentence of death. A firing squad executed Ciano, Marshal de Bono, Giovanni Marinelli, Carlo Pareschi, and Luciano Gottardi on the morning of 11 January 1944. The Council of Ministers spared Cianetti’s life with a prison sentence of 30 years.

Armed Forces of Repubblica Sociale Italiana

In the fall of 1943, the RSI’s needed to address their ability to develop an army. Most males of draft age were either captured by the Allies, interned by the Germans, in important industry positions, or located in liberated Italy.

Italian armament was also exhausted. An inventory done by Marshal Alfred Jodl showed that on 8 September 1943, 1,255,660 rifles, 38,383 machine guns, 9,986 artillery pieces, 15,500 vehicles, 6,760 mules, and horse were confiscated. Approximately 600,00 Italian soldiers became interned in German camps.

Renato Ricci proposed a party militia modeled after the German SS to quell civil unrest and partisan actions. He also wanted to create a small but efficient navy and air force. In doing so, it would allow the Wehrmacht to freely defend the front on the Italian peninsula.

Graziani proposed the creation of 25 divisions, made mostly of eligible draftees and voluntary interns. German authorities did not accept this proposition. Even Ricci and Pavolini secretly disapproved of this because they felt it would give Graziani too much leverage in politics. Graziani was quick to note that it was the Italian government that turned their back on Germany, not its soldiers.

Italian Social Republic flag used by its armed forces during war.

An agreed-upon compromise sought to create four divisions made of 12,000 interned volunteers and 51,162 through conscription. A militia made up of Brigate Nere (Black Brigades) and Republican Police and the Guardia Nazionale Repubblicana (GNR) or Republic National Guard. A total of 200,000 Italians made up the RSI armed forces at the end of 1943.

The armed forces of the RSI included the following organizations:

National Republican Army

After the armistice, thousands of Italian soldiers became prisoners and interned in Germany. When Mussolini formed the RSI, these men gained the opportunity to fight again and fill the ranks of the new National Republican Army. To those that did, they obtained training in Germany and sent back to Italy in the summer of 1944. These retrained soldiers ultimately led to the creation of four divisions of the army:

The National Republican Army included four divisions trained in Germany.

- 1st Alpine Division “Monterosa.” Trained in Munzingen, Baden-Württemberg

- 2nd Infantry Division “Littorio.” Trained in Sennelager in Wurttemberg.

- 3rd Marine Division “San Marco.” Trained in Grafenwoer.

- 4th Bersaglieri Division “Italia.” Trained in Heuberg.

These four divisions, along with 3 German ones, became the Liguria Army. They deployed in the alpine region and the coastal zones of Genoa and La Spezia to thwart a possible Allied landing in those areas. They were, in all respects, first-line divisions.

General Mario Carloni (L), Commander of the Monterosa Division reviews his troops with Benito Mussolini at the Munzingen training grounds.

However, the most significant military effort taken by the RSI included anti-partisan activities. In these actions, thousands of soldiers and militia members committed unspeakable atrocities against partisans and civilians.

When moral began to sink, the desertion rate would climb, sometimes reaching 25%, affecting the combat readiness of such units. In 50 days, the “Monterosa” division lost 1,105 men, and the “San Marco” lost 1,400.

But a point to mention is that the Monterosa division would see the most action in the remaining year of World War II. They also showed stiff resistance in the Battle of Garfagnana between 26-28 December 1944.

Republican National Guard (Guardia Nazionale Repubblicana) or GNR

From the ashes of the old fascist militia (MVSN), the RSI created the new Republican National Guard (GNR). The GNR operated as the internal police of the RSI. They garrisoned strategic locations and infrastructures and also participated in the anti-partisan activities. The GNR formed the only armored unit of the RSI, the Gruppo corazzato “Leonessa.” This unit included 30 M13/40 tanks, a few self-propelled guns, 16 armored cars, and 16 tankettes.

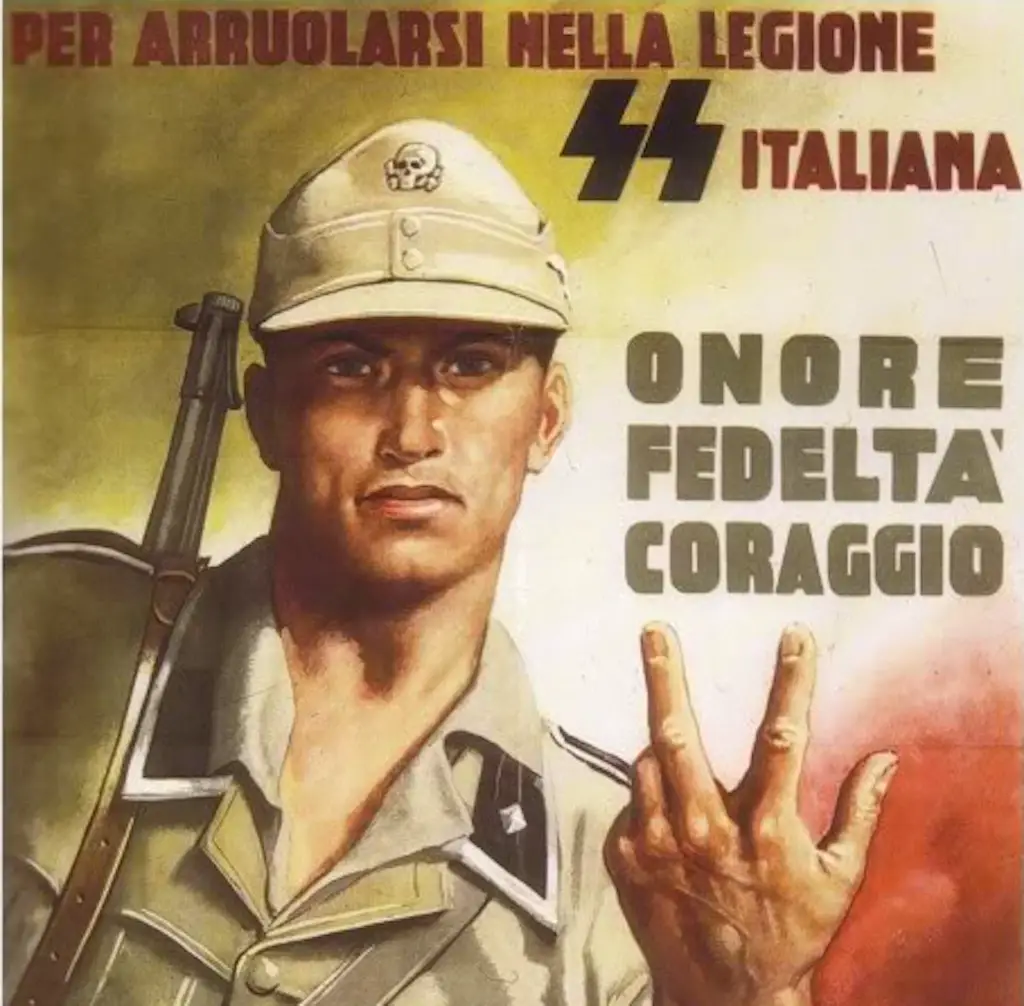

Italian SS

By orders of the German General Wolff through Himmler, 6,000 repatriated Italian interns formed the 29th Waffen Grenadier Division for anti-partisan duties under the direct control of Germany with an oath to Hitler. It was also known as the SS (1st Italian) or the Legione SS Italiana.

Italian SS poster.

Dissolution of the Carabinieri

In October 1943, the Germans demanded the liquidation of the Carabinieri, a predominantly monarchist armed police force. Marshal Graziani, knowing this German order would cause a lot of friction with the Italian population, plotted a way to end their existence without showing it as a German order. He called on Col. Casimiro Delfini on 4 October. He gave him an impossible order…” send 9,000 Carabinieri to Zara and defend it against the Slavs”. Delfini could not oblige. Most Carabinieri were not combatants and only conducted police work. Graziani knew this could be his only response. Therefore, the GNR subsequently absorbed the Carabinieri, along with the MVSN.

Black Brigades

The Black Brigades were the paramilitary force of the Republican Fascist Party. They enlisted volunteers from the age of 18 to 60 years old. Many fanatics, old fascists veterans, and young men who glorified Mussolini filled its ranks. The Brigades supported the GNR and gained a reputation for their brutality and violence.

National Republican Aviation

In October 1943, Lt. Col Ernesto Botto and Luftwaffe Commander Generalfeldmarchall Wolfram von Richthofen reached an agreement in which named Lt. Col Giuseppe Baylon head of the Italian Air Ministry.

This new Air Force would be named the Republican National Air Force (ANR). Initially, it was quite challenging to create a capable air force because the Germans captured approximately 1,000 Italian aircraft remaining in German-controlled areas. Towards the end of 1943, Germany returned several Macchi C.205 V back to the Italians to form the Iº Gruppo Caccia, which debuted over Turin on 3 January 1944.

Next came the Squadriglia Complementare Montefusco, equippied with Fiat G.55’s and the IIº Gruppo Caccia, which formed in April, 1944. The IIIº Gruppo Caccia formed in summer 1944, but never achieved combat status.

ANR Air War Against Allies

Losses were very high, and the lack of spare parts made it quite challenging to maintain aircraft at the ready. In most situations, the Italian pilots required additional training to fly the German BF 109G due to the high losses of their domestic aircraft.

In August 1944, the Germans tried to disband the ANR to force Italian pilots into the Luftwaffe. The pilots refused and burned their aircraft after SS units surrounded their bases. The crisis became resolved when German authorities reversed their decision.

A Fiat G.55 of the Squadriglia Bonet of the Aeronautica Nazionale Repubblicana.

During the last year of war in Northern Italy, the ANR had the only Axis aircraft flying in the region. During the period it flew Macchis, the Iº Gruppo Caccia claimed 100 Allied aircraft with the same number of losses. It downed more aircraft than any other Italian unit of its size.

Defending the northern Italy air space became a huge endeavor for the three operational ANR fighter squadrons. They faced hundreds of allied aircraft and subsequently withdrew from the theatre along with the Luftwaffe.

The ANR fought to the very end, with the last mission conducted on 19 April 1945 over Turin. The ANR also operated the “Faggioni” torpedo-bomber squadron, initially flying one old SM.79, which saw action during the axis counterattacks against the allied landing in Anzio. The tri-motor compliment eventually numbered 27 aircraft.

RSI Navy

Most of the Regia Marina sailed to Malta as part of the instrument of surrender. What remained with the RSI was a minimal naval force. Four Mas, two anti-submarine vessels, and various other light vessels. There were five submarines stationed at Betsom and five in the Black Sea.

The submarines at Betasom remained in RSI hands once Enzo Grossi, Commander of Betasom, reassured the Germans of his loyalty and raised the RSI flag on 12 September 1943.

The story of the Italian submarines stationed in Romania is a revelation of the strange relationship between Axis partners. On 14 November 1943, a deal became established with the Romanian government for the transfer of the submarines to Romanian control.

Even though Romania recognized RSI as the legitimate Italian government, they protested and stalled for almost seven months in returning the five submarines into Italian hands. A subsequent letter from Mussolini to Ion Antonescu on 14 January 1944 met with little results. Only four submarines returned in July 1944 – because that is all the RSI could afford to pay Romania after they sent the maintenance bill to Italy.

The RSI navy did not have any effect during the remainder of the war. By German order, the only naval vessels allowed to carry the Italian flag were those dependent on the X Flottiglia Mas (Xª Mas).

Decima MAS (X° MAS) of the RSI

In the days following the armistice, Junio Valerio Borghese, commander of the X° flotilla MAS of the Regia Marina, chose to fight alongside the Germans. There were 1,300 X Mas members still present at La Spezia. Oberkommando der Marine Admiral Karl Dönitz provided Junio Borghese the approval to acquire a Naval Infantry comprising 8,000 men of frogmen, I, and II Combat Group, various autonomous battalions and infantry companies. It also included a women’s auxiliary unit.

A 1944 photo of Junio Valerio Borghese with a German official to his left.

These battalions obtained the respect of both German and Allied forces. However, the X° Mas still felt the sting of German occupancy. To garnish needed supplies, members of the X° Mas would meet German authorities at a Beretta manufacturer, get them drunk and steal the necessary weapons.

In other situations, they traded pigs for German cannons, managing to assemble four batteries of 152/32 cannons. On another occasion, a Xa MAS Lieutenant received a promotion for stealing 5,000 liters of fuel from under the nose of Germans.

The distinctive “X” patch of the Decima MAS.

During the war, his legendary actions attracted many motivated young men, born and raised under Mussolini’s regime. With German help, Borghese trained and equipped these men. He created the elite infantry division renamed X° flotilla MAS or X° MAS (not to be confused with the special unit of the Regia Marina). Borghese, much closer to the Germans than to the RSI government, enjoyed considerable autonomy. His unit actively conducted anti-partisan activities while also committed several war crimes. The X° flotilla MAS also engaged the allies during the Anzio campaign.

Salo Republic Treatment of Jews

In the summer of 1943, approximately 40,157 Jews were living in Italy. Of these, 6,500 were non-Italians. Italy had laws discriminating against Jews as of 1938 after the publication of the Race Manifest. But no substantial actions were placed against them. In fact, in the first few years after Italy’s entry into the war, Adolf Eichman announced that the French, Yugoslav and Greek zones occupied by the Italians had become a Jewish refuge. The protection of jews changed after the fall of Italy.

On 16 October 1943, German authorities arrested 1,259 individuals. Of these, the Germans released approximately 200 because they were not Jewish. German authorities sent 1,022 to Auschwitz-Birkenau. About 839 did not meet labor standards and became exterminated. Of this initial Jewish group, only 17 survived the war.

A panoramic of the Fossoli Jewish camp. Image: Fondazionefossoli

Mussolini was aware of Germany’s deportation of Italian Jews. His official position was an endorsement. However, it irritated him by the fact that these actions seemed to undermine his government’s legitimacy. On 5 December 1943, the first Italian internment camp specifically for the Jews opened in Fossoli. Additionally, the Office of Races (Ufficio per la Razza) opened on 15 March 1944.

Of the 10,000 Italian Jews shipped to concentration camps, approximately 7,700 died.

Losing the War

By January 1945, the Russians entered Germany, and the war was all but lost. Mussolini held hope in Hitler’s “Secret Weapons” to change the balance of the war, but never felt convinced they would work. Mussolini was upset that Germany never gave him the authority he needed to do what he felt was necessary. Graziani was frustrated that Germany could not trust the Italian military with independent military actions.

Mussolini decided to move his government to Milan, where he could initiate contacts with the Allies. If these contacts did not bear favorable terms of surrender, he would establish a final front in Valtellina. This Allies would accept none other than unconditional surrender. To Mussolini’s dismay, only 2,000 to 5,000 soldiers could be mustered for what he perceived as a “final heroic stand.”

On 18 December 1944, Mussolini had moved his office to Milan. German Ambassador Rahn suggested he move to Merano or the Brenner Pass. However, Mussolini chose Milano due in part to his wish to distance himself from German authority.

On 25 April 1945, Graziani informed Mussolini of the imminent surrender of German forces in Italy. Mussolini planned a radio broadcast announcing the Germans as turncoats, but events unfolded too quickly. That evening, Mussolini attempted to flee. He brought with him documents for use as leverage to any war crimes trial. These documents are still a subject of great mystery. Even the details of this escape are sketchy. However, Valtellina, Switzerland, or other areas controlled by the Wehrmacht are the most likely areas.

Death of Mussolini and End of the RSI

On 27 April 1945, partisans stopped Mussolini’s convoy at Musso, near Dongo. On the morning of 28 April 1945, Partisans shot and killed Mussolini, his mistress Clara Petacci, and other convoy members. Their bodies hanged for display the following day in a piazza in Milano.

The bodies of Nicola Bombacci, Mussolini, Petacci, Pavolini and Starace hung in Piazzale Loreto, Milan 1945.

Related: The Final Hours Leading to Mussolini’s Death

German troops surrendered in Italy on 2 May 1945, and the RSI ceased to exist. In the end, The RSI could not function as a state with the overbearing German occupation and the pressure of Partisan attacks.

The liberation of Northern Italy and the death of Mussolini on 28 April 1945 ended the Italian Social Republic’s short existence.

Partisans killed approximately 13,000 Italian Social Republic military members by the end of the war. Other sources claim as many as 21,600 died at the hands of partisans. Fascists forces killed approximately 15,000 partisans. Some estimates list partisan deaths at 35,000 or more.

The RSI was ultimately a puppet government in the hands of the Germans, chaired by a powerless and depressed Mussolini. Beneath the Duce, several fascist extremists unleashed their violence, revenge, or looted as much as possible in the increasingly chaotic and bloody Italian civil war within the world war.

Sources

Montanelli I., Io e il Duce, Rizzoli (2018)

Jowett P., L’esercito italiano nella Seconda guerra mondiale, LEG edizioni (2019)

La Guerra Aerea in Italia, DELTA editrice (2019)

anpi.it (2016)

Istituto Luigi Sturzo, La Repubblica Sociale Italiana e la Resistenza

Benito Mussolini by Gino Avolio, 2000

La Repubblica di Mussolini by Giorgio Bocca