Background on the Corpo Aereo Italiano (CAI)

The Corpo Aereo Italiano (CAI) was the Italian air contingent sent to Belgium to assist the Germans in the air war against the British

Mussolini was very keen on showing the Italian colors over Britain, mainly for propaganda reasons. In spite of little interest on the German side, an agreement was nevertheless made that the Italian Air Force would establish a combined air fleet operating out of bases in Belgium within their own dedicated operational sectors. The CAI was officially established on 10 September 1940.

The first bombers arrived in Melsbroek, Belgium on 25 September 1940. The first bombing raid on Britain occurred on the night of the 24th and 25th of October 1940. Italian participation in the Battle of Britain lasted from 25 October 1940 to 3 January 1941*.

A color photograph of a BR.20 with the 242a Squadriglia assigned to the Corpo Aero Italiano in the Battle of Britain.

Corpo Aero Italiano Order of Battle

CAI Commanding Officer: General Squadra Aerea Rino Corso-Fougier

13º Stormo

Based in Melsbroek, Belgium.

Commanding Officer: Colonel Carlo de Capoa.

38 Fiat BR.20 aircraft in total.

A. 11º Gruppo (Commanding Officer: Major Giuseppe Aini)

- 1a and 4a Squadriglia

B. 43o Gruppo (Commanding Officer: Major Giulio Monteleone)

- 3a and 5a Squadriglia

43º Stormo

Based in Chièvres, Belgium.

Commanding Officer: Colonel Luigi Questa.

27 Fiat Br.20 in total.

A. 98o Gruppo (Commanding Officer: Giuseppe Tenti)

- 240a and 241a Squadriglia

B. 99o Gruppo (Commanding Officer: Major Gian Battista Ciccu)

- 242a and 243a Squadriglia

56º Stormo

Commander Officer: Colonel Umberto Chiesa

A. 18º Gruppo (Commanding Officer: Major Ferruccio Vosilla)

- 83a, 85a and 95a Squadriglia.

- Based in Ursel, Belgium.

- 50 Fiat CR.42 in total.

B. 20º Gruppo (Commanding Officer: Major Mario Bonzano)

- 351a, 352a and 353a Squadriglia.

- Based in Ursel, Belgium then Flugplatz Maldegem, Belgium.

- 48 Fiat G.50Bis in total.

179a Squadriglia

Commanding Officer: Captain Perelli Cippo.

Based in Melsbroek, Belgium.

5 CANT Z.1007’s (Reconnaissance) in total.

Aircraft of the CAI

Seemingly a well-balanced force, the Corpo Aereo Italiano consisted at the planning stage of two wings of each 40 bombers and a similar number of fighters of the Fiat CR.42 and Fiat G.50bis types. For reconnaissance, there were some three-engine Cant Z.1007bis, twelve Caproni 133Ts, and one Savoia-Marchetti S.75, with nine Ca164s for communications. The Italians obtained a Ju 52 on loan to operate as a transport link between the main base in Belgium, Evere, and Rome. The bomber wings consisted of the Fiat BR.20M, in all approximately 200 aircraft.

Arrival in Belgium

Most of the Copro Aero Italiano bombers arrived at the Chievres airbase, Belgium between 25-27 September 1940. Three of the 40 aircraft of the 43rd Wing crashed en route due to icing and technical problems, and some made intermediate landings in Germany to fly on later. One of the 37 aircraft of the 18th Wing also crashed, and some others made fuel and oil stops on their way. In the afternoon of 27 September 1940, there were 60 Italian bombers on Belgian soil.

Effectiveness of Corpo Aereo Italiano

Could these have made a difference in the upcoming air/naval battles around the south-eastern coast of England?

The fighter compliment of the Corpo Aereo Italiano did not arrive in Belgium until a couple of weeks later, so the Italian bombers would have had to operate without their own dedicated fighter escort or with German escorts. That actually took place a couple of times during the fall. To operate without fighter escort against the enemy navy would be less risky than intruder missions over British territory due to enemy fighter defense. Mainly because the Fighter Command would have problems with flying combat air patrols all the time, but also because it probably already would swarm with German planes from the dedicated anti-ship units (and others) around any enemy naval incursions.

The CAI did not fly its first mission before 23 October 1940, simply because its fighters had been delayed in Italy. But that does not mean their bombers could not have started independent operations in the case of an ongoing invasion. Both their bombers and reconnaissance planes could certainly have contributed to the total invasion effort, but the general opinion is that the Italians were totally useless, nothing more than sitting ducks for the RAF. A proper look into the subject shows that they performed as well, if not better, than their opponents’ bomber units at the time.

Italian Pilots and Aircraft

Italian pilots were good, particularly their fighter pilots. Laddie Lucas, in his book about the fight for Malta, is very generous in his description of his opponents. There was a great tradition of aviation in Italy, and their air force participated in several great long-distance ventures between the wars. The fighter equipment was not up to date in fall 1940 as their main fighter models, the Fiat CR.42 and G.50, were underpowered and under-gunned but very maneuverable.

Fiat Br.20M Bombers

The Fiat BR.20M bomber, however, was on par with anything the RAF had. It flew faster than the Hampden, Wellington, and Beaufort with a better bomb-load combination (except for the Wellington), and it had a more powerful defensive armament, fielding three 12.7mm (.50 caliber) Breda machine guns. It served well with Franco’s forces during the Spanish Civil War and for the Japanese during the Second Sino-Japanese War. If anything, it had a weakness in that its engines consumed so much oil that its range became restricted. Most of the BR.20s that failed to cover the distance from Italy to Belgium in one hop had to land for the refilling of oil. For operational sorties over England, this was not a problem due to the shorter distances involved there.

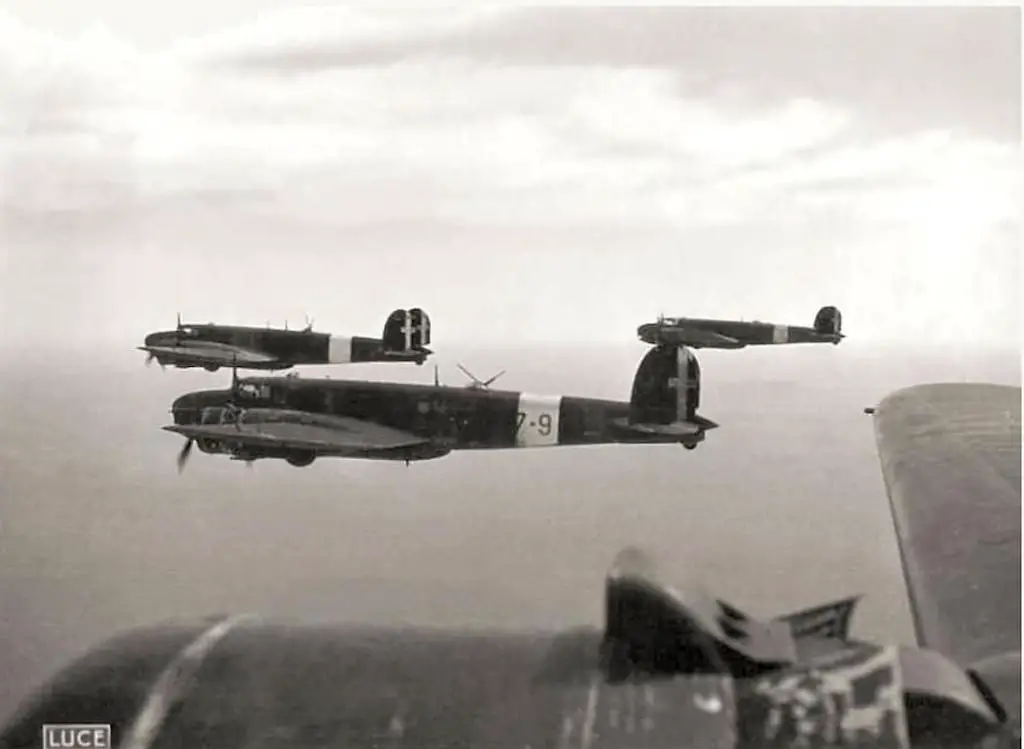

Fiat Br.20 Cicogna bombers in flight.

To believe that the Italian bombers could have gone straight into battle is not realistic. Given a few days, however, under an immediate urge to support their allies, it would have been possible. Particularly if their missions covered the easily-navigated area between the Thames Estuary and the Belgian coast, which they actually did. The Fiats could carry a large variety of bomb-loads, ranging from 20 to 800-kilogram bombs, weapons powerful enough to sink or damage larger warships. It could also carry a bomb dispenser system with four bombs containing a total of 720 bomblets, 1 to 2 kilogram anti-personnel or incendiary bombs.

Battle of Britain Bombing Results

But they were shot down in droves, were they not? Not really. If you compare the Italian losses with similar daylight British losses over the Continent, they were rather less than more. In the first night-bombing mission on October 24, 1940, none of the 16 participating Fiats fell to enemy action. The British reported little practical damage, not so strange since the bombings occurred from 5,000 meters altitude.

On October 29, 1940, the first daylight raid flew with 15 Fiats participating. The bomber unit overflew Ramsgate at a relatively low altitude in a tight wingtip-to-wingtip formation which flabbergasted the anti-air gun crews. The Italian bombers were described as standing out as peacocks due to their lively camouflage. The British guns were able to do damage to five of the Italians; one of them force-landed in Belgium, the others made it back to their base after 75 bombs had been dropped on Ramsgate.

On the night of November 5/6, 1940, 13 Fiats flew a night sortie over Harwich and Ipswich without losses. Without any triumphs to report, the best the English newspapers could report on was the awakened citizens who complained that the Italian aircrafts sounded like “rattling tin cans.” In other words, they made little difference.

Quite a few missions flew with more losses generated by mechanical failures than enemy action.

Conflicting Accounts

On November 11, 1940, came the mission that probably contributed the most to the bad reputation of the Corpo Aereo Italiano. Ten BR.20M’s took off around midday, each of them loaded with three 250 kilogram bombs. They flew the route Bruges-Ostend-Harwich and approached Harwich at 14:40 at 3,700 meters. Bad weather resulted in most of the escort force not showing up. Of the 42 CR.42s, 46 G.50s, and some Luftwaffe Bf 109s, only the CR.42’s were in the vicinity. The Italian formation encountered parts of four Hurricane and Spitfire squadrons, which radar controllers had scrambled. One squadron already was in the area flying a routine patrol. The Fiat fighters soon had their hands full defending themselves, leaving the bombers to their destiny.

After the battle the RAF fighter pilots made claims of nine BR.20Ms shot down and one damaged, which was the whole strength of the formation. In reality, three had been shot down. The Italians claimed nine British fighters shot down while only two, in reality, received any damage. With claims such as these, there were bound to be some false impressions.

The CAI returned to Italy during the first half of 1941.

* G.50s from the 352a and 353a Squadriglia stayed in Belgium until 15 April 1941 conducting convoy escort duties leaving from Dunkirk.