Debate on Italian Aircraft Carriers and Aviation in the Regia Marina

During the 1920s and 1930s, debate raged among the Italian high command. Many contentious issues vied for the attention of Il Duce. Of these, a particularly divisive matter was the future of Italian naval aviation. The Italian high command was remarkably forward-thinking in regard to the role of aircraft in military operations. As such, even Italian Chiefs of Staff such as Gino Ducci were among the champions of the fleet air arm.

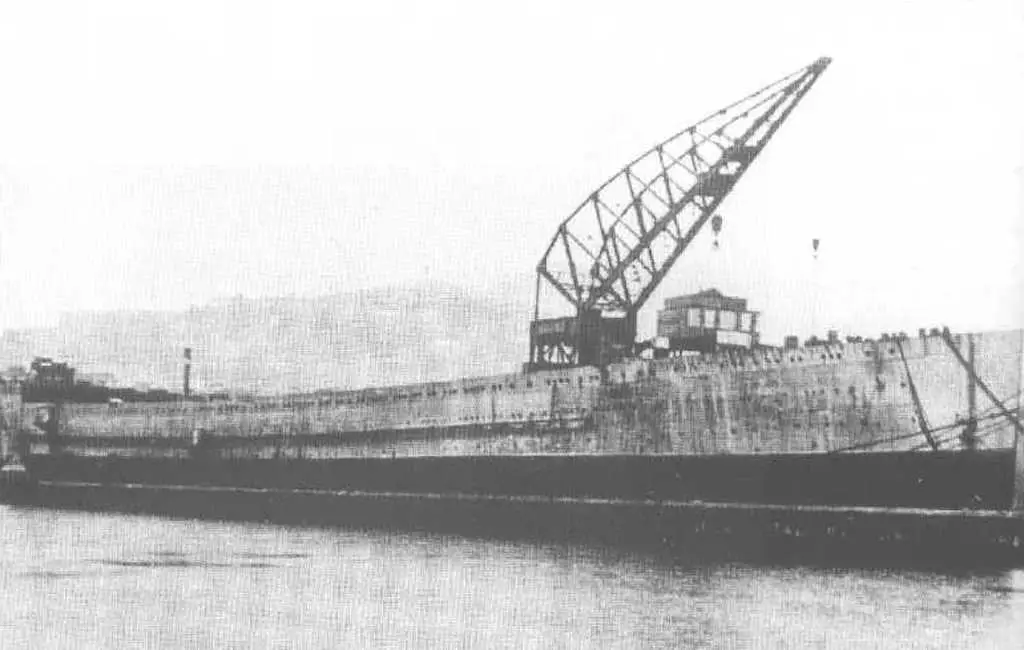

The Aquila moored in La Spezia.

No one would discount the value of aircraft carriers entirely. However, Italy’s held limited resources for military construction, and aircraft carriers were an unproven weapon. It was truly their marginal utility that debate fell upon. After all, Italy jutted out into the Mediterranean Sea and possessed bases on numerous Mediterranean islands. It was not until the outbreak of war that the shortcomings of the ‘unsinkable aircraft carrier’ concept became evident.

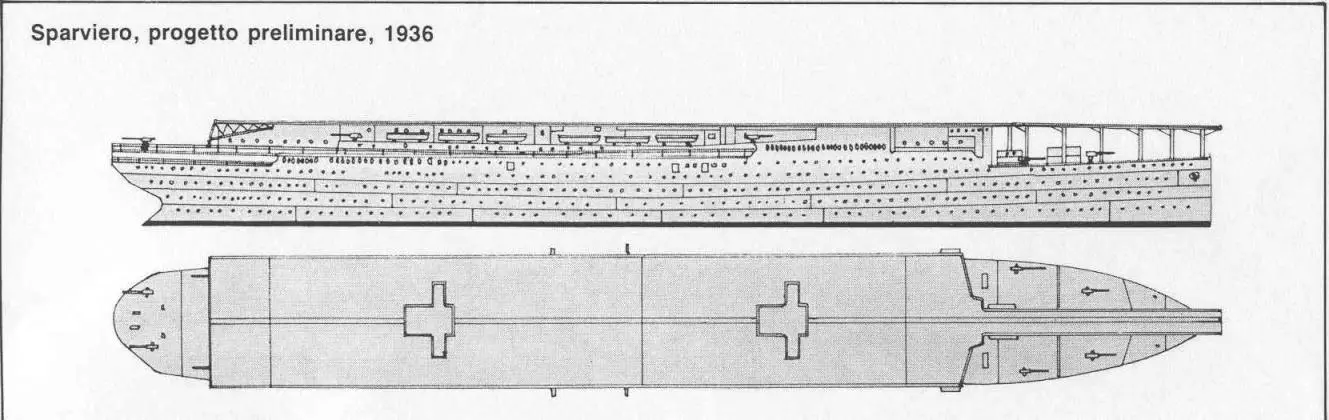

Sparviero

Practical reality triumphed over theoretic possibility, and no one could deny the necessity of aircraft carriers. While construction of the Italian aircraft carriers Aquila and Sparviero eventually neared completion, neither was ever combat worthy. Ultimately, the fate of the ships was to sail to the scrapyards in the early 1950s.

The Development of Italian Naval Aviation

The significant establishment forces standing against aircraft carrier construction did not prevent experimentation. Giuseppe Miraglia began her life as a civilian train ferry in 1923, but the Regia Marina soon acquired her. Damages from a heavy storm disrupted her conversion to a seaplane tender in 1925, which was nonetheless completed in 1927. The small, slow ship carried 296 men, cruised at 21 knots, and carried only sixteen seaplanes. However, she represented a tentative step forward in naval aviation. Despite her service in the Ethiopian and Spanish wars, this foray into the employment of naval aircraft found a dead end.

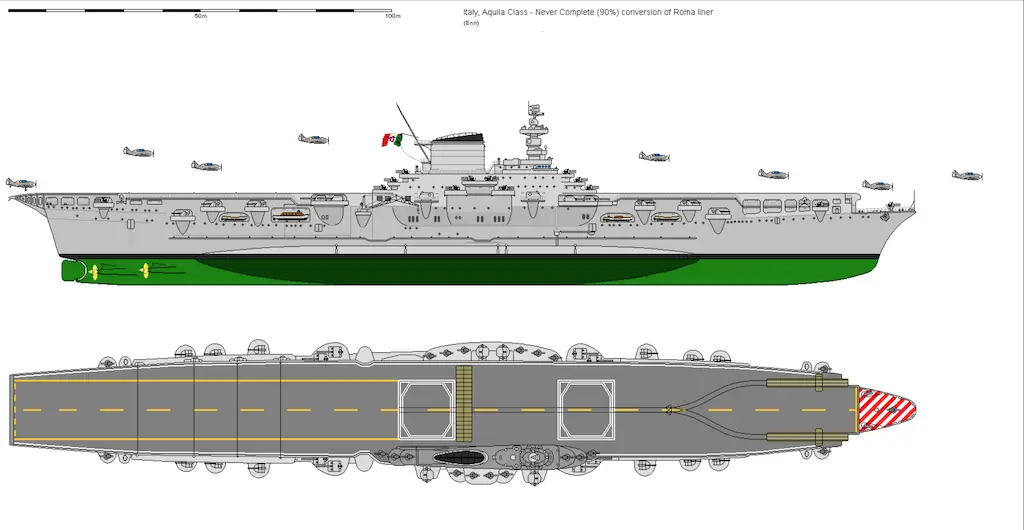

The Italian carrier Aquila profile.

Political developments forced the hand of the Italian command and pushed naval aviation to the sidelines. The primary task of the Regia Marina was to maintain parity with the navy of Italy’s chief rival, France. As the French embarked on a building program focused on battleships and heavy cruisers, Italy fought to keep up. The construction of ships such as the first-rate Zara cruisers and Littorio battleships swallowed her ship construction capacity. Nonetheless, hypothetical interest in developing Italian aircraft carriers persisted. A simple conversion of the ocean liner MS Augustus into an auxiliary carrier laid in limbo until two disasters revived interest.

The Italian carrier Sparviero profile.

First, the defeat at Taranto demonstrated the offensive power of British naval aviation. Previously, the Regia Marina began a conversion of SS Roma, the sister of MS Augustus. The original intention was only to produce another auxiliary carrier, but there was no longer doubt as to the merit of naval aviation. It inspired Mussolini’s ambitious order to convert the ocean liner SS Roma to a fleet aircraft carrier, christened Aquila. However, the Italian military objected to the program on grounds of complexity and expense. Not until the Battle of Gaudo/Cape Matapan cost the Regia Marina an entire cruiser division later that year did they come onboard.

In the next year, Italian command revived the plan to reconstruct MS Augustus as an auxiliary carrier, Sparviero.

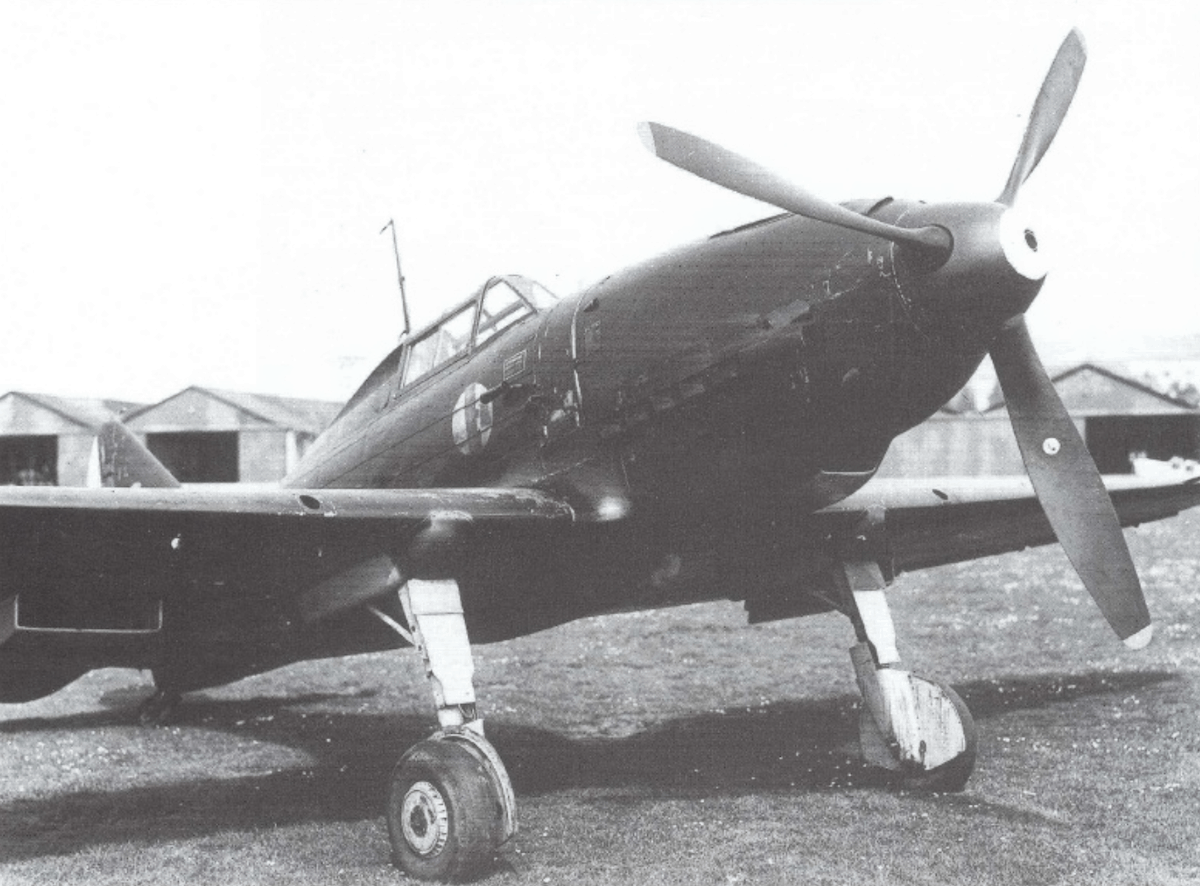

Aircraft Carrier Aquila

Aquila was the more ambitious project of the Italian aircraft carrier program. By the time of the 1943 Armistice of Cassibile, she had progressed further along than her sister and neared completion. Her projected complement stood at 1,313 sailors and 107 officers. The gutted interior provided room for workshops, modest torpedo defenses, a new propulsion system, and a hangar. Eight boilers powered four steam-geared turbines, which produced 151,000 shp and enabled Aquila to propel herself at 30 knots. The hangar was sufficiently spacious to carry 41 of the capable Reggiane Re.2001 aircraft. The 211.6 m × 25.2 m deck carried an additional ten planes, providing a total capacity of 51 fighter-bombers. To transfer aircraft from one to the other, the ship possessed two 15m elevators.

Reggiane RE 2001 Serie II was designed for use on Italian aircraft carriers.

Additionally, the deck was partially armored. Fuel and ammunition storage enjoyed 76mm of armor protection. The interior carried 30-80mm of reinforced concrete protection, to protect the internals from splintering. Her defensive armament was quite good, as well. She bristled with a powerful defensive array consisting of 135mm and 20mm guns. The eight heavy AA guns provided a powerful wall of flack against enemy planes. Rounding out this defense, Aquila carried 132 20mm guns, in six-barreled mounts.

The Aquila aircraft carrier moored at the port of Genoa in 1946.

In all, Aquila had the makings of a respectable aircraft carrier for operations within the Mediterranean Theater. However, the unique problems of naval aviation posed significant challenges to her prospective operations. The limitation of 51 planes to her air group was due to Italy’s lack of a folding-wing aircraft. With a folding wing variant, she’d have possessed a much more powerful striking arm. Additionally, trouble with the arrester gear was a critical failure that delayed her entry into service.

Aquila Specifications

| Class | Aquila |

|---|---|

| Type | Aircraft Carrier |

| Armor | 30mm-80mm |

| Displacement | 27,800 tons |

| Length | 763 ft (232.5 m) |

| Beam | 98 ft 5 in (30 m) |

| Propulsion | 151,000 shp (113,000 kW) 4 Steam Turbines |

| Speed | 30 knots |

| Range | 5,500 nm |

| Crew | 1,420 |

| Armament | (8) 135 mm guns (12) 65 mm guns (132) 20 mm anti-aircraft cannons |

| Aircraft | 51 |

Aircraft Carrier Sparviero

Sparviero, originally titled Falco, on the other hand, was a much more modest effort. It originally began in 1936 but languished for years until being resumed in September. While Aquila represented an impressive reconstruction, the internals from the luxury liner days of MS Augustus largely remained within Sparviero. Her diesel propulsion would’ve provided a speed around 20 knots, the small hangar could only afford a 34-fighter air group.

A rare photo showing the aircraft carrier Sparviero under construction in 1942.

This is all extremely theoretical, however; the only work which the Genoa shipyards completed was the removal of the superstructure. Sources on the plans for it are obscure and often contradictory. Sources sometimes report the anti-air defenses, armor, and crew size as identical to Aquila. This seems improbable, however, given the relatively narrow scope of the reconstruction.

Sparviero Specifications

| Class | Sparviero |

|---|---|

| Type | Aircraft Carrier |

| Armor | 70mm-80mm |

| Displacement | 30,408 tons |

| Length | 664 ft (202.4 m) |

| Beam | 82 ft 8 in (25.2 m) |

| Propulsion | 28,000 shp (21,000 kW) Diesel Motors |

| Speed | 18 knots |

| Range | |

| Crew | 1,420 |

| Armament | (8) 135 mm guns (12) 65 mm guns (22) 20 mm anti-aircraft cannons |

| Aircraft | 25-34 |

Fate of the World War Two Italian Aircraft Carriers

If one felt harsh, they might say Sparviero’s life began and ended with a whimper. Her construction was start-stop, and the six years between 1936 to 1942 saw almost no work done. After being captured by the Germans in 1943, they sank Sparviero in Genoa harbor a year later to deny the use of the port to the allies. Bureaucratic inefficiency, a skeptical military establishment, and industrial weakness ended the career of the ship before it began. Ironically, even the scrapping of the ship dragged on for years – beginning in 1946, completing in 1951.

Only the bow of the scuttled Sparviero can be seen at Genoa Harbor, 1943.

However, even in her inaction, Aquila showed positively what the Italian military could accomplish. In two years, with fairly limited technical assistance, they completed a competent Italian aircraft carrier. They quickly achieved inroads on various forms of advanced equipment, until the 1943 armistice removed Italy from the war.

German forces seized the vessel and it suffered considerable damage from Allied bombardment while moored at the port of Genoa on 16 June 1944. Co-belligerent Italian forces of the former Decima MAS partially sank the carrier on 19 April 1945 before another German attempt to scuttle the vessel to block the port of Genoa.

Although the Aquila was raised in 1946 it met the scrapyard in 1952. The frenetic construction of that aircraft carrier holds much more interest. Had the political will to construct her been found six years earlier, one has to wonder how they’d have changed the Mediterranean war.