More than a year before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, carrier-based planes surprised and smashed a navy’s battleships while they were anchored in their home port. It was the Battle of Taranto, a fine harbor located in the instep of the Italian boot; the planes belonged to the Royal Navy.

What was the Battle of Taranto?

On the night of November 11, 1940, twenty planes flew from the deck of HMS Illustrious, then located 170 miles from Taranto. Eleven of those planes carried torpedoes, and five of those hit three Italian battleships. Littorio and Caio Duilio suffered severe damage requiring months of repairs. The Conte di Cavour sank and never sailed again. The other aircraft carried bombs, and they inflicted damage on smaller ships, harbor facilities, and a seaplane hangar. Only two planes were lost, and Illustrious and her escorts returned safely to their base at Alexandria.

The Conte di Cavour sinks in shallow water following the Battle of Taranto.

An Observant LCDR

With the Mediterranean Fleet tied up at the Alexandria docks, a man in street clothes quickly left Illustrious and traveled to the American Legation. He was Lt. Commander John N. Opie, III, USN. Opie immediately began work on a report of his observations while aboard the carrier. He had looked over the shoulder of radar operators as they identified Italian planes and vectored fighters on to their locations. Opie had sat in on the pilots’ pre-flight briefing and shared whiskey and eggs with them after they returned. He had seen the reconnaissance photos that showed ship locations, barrage balloons, and anti-aircraft guns.

Opie had watched aircraft take-offs and landings from the “goofers’ gallery,” an observation deck built into the carrier’s island. He had seen the aircraft armed with their bombs and torpedoes and observed the method developed by the Royal Navy to control the initial dive of air-launched torpedoes, thereby allowing those torpedoes to operate in shallow water. This report would go to the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations and the Office of Naval Intelligence in Washington, D.C. More on Opie and his report later; but first, a look at the details of the British attack.

LCDR John N. Opie, III, USN. Photo copyright: Christopher O’Connor.

Arrival of the Illustrious

The Battle of Taranto became possible following the arrival of Illustrious in August. Newly commissioned, she was the best carrier in the Royal Navy. Joined with HMS Eagle, she gave the Mediterranean Fleet a strong air arm. Illustrious was built with an armored flight deck, allowing her to operate in areas where the enemy’s land-based air power was always a threat. She took to sea the radar and fighter control techniques that had recently won the Battle of Britain. Her pilots and those of Eagle were well-trained and experienced.

The Fleet commander, Admiral Andrew B. Cunningham, immediately put his two carriers to work, attacking remote ports and bases such as Benghazi, Rhodes, Leros, and Tobruk. These attacks, conducted in September and October, gave the pilots further combat experience and sharpened their skills. The Royal Navy attacked at night, unlike any other navy in the world.

Use of Air Reconnaissance

In September, an RAF photo squadron established itself on Malta. This squadron, flying Martin Maryland medium bombers, began to routinely fly photo missions over Italian ports, locating the ships of the Italian Fleet, and documenting the layout of the harbors and the harbor defenses. With good intelligence and a well-drilled air arm, Admiral Cunningham resolved to attack the Italians at one of their major bases.

Preparing for Attack

He had hoped to make the attack on October 21, the anniversary of Admiral Nelson’s great victory at Trafalgar, but an accident and fire aboard Illustrious caused a delay. On November 4, 1940, the British kicked off the Taranto attack by going to sea at both ends of the Mediterranean.

A Game of Chess

Convoys left Gibraltar headed for Malta and left Alexandria with deliveries scheduled for Crete, Athens, and Malta. The convoy escorts included warships transferring from Force H, the Gibraltar-based flotilla, to the Med Fleet. The Italians observed these movements and tried to attack, but the radar on the British carriers identified the incoming Italian planes at 50 miles or more, and fighter planes drove them off. The ships converged on Malta from the east and west, delivered men and material to the island, and then began moving back to their bases.

At this point, the Italians seemed to have relaxed a bit, because they did not track Illustrious (Eagle was not able to participate, a victim of near misses from Italian bombers) as she moved east and then northeast to her launch point off the island of Cephalonia. The base at Taranto was in a high state of readiness – guns manned and ammunition at the ready. But they were not aware that the carrier was approaching. At around 8 pm, the first wave of 12 planes launched.

RAF torpedo bomber Fairey Swordfish

Launching of the Fairey Swordfish

All the planes were Fairey Swordfish, a fabric-covered biplane that had already been detailed for retirement. The Swordfish, powered by one 860 horsepower engine, was a perfect torpedo plane. Dropping a torpedo from an aircraft required a plane to fly low and slow; the Swordfish was incapable of flying very high or very fast. Two planes carried flares to drop along the eastern shore of the harbor, silhouetting the targets from the attackers flying in from the west. Six planes carried torpedoes and would target battleships. The other four carried bombs to attack the base and the smaller ships in the harbor.

On the torpedo planes, a drum of wire latched under the nose of the plane, with the wire connected to the nose of the torpedo. As the torpedo fell, the tension in the wire kept the torpedo’s nose up. It would ensure a ‘belly flop’ rather than a ‘nosedive’ when hitting the water. This reduced the initial dive and allowed the torpedo to be successfully dropped in shallow water.

Battle of Taranto Begins

The bombing of Taranto began at about 11 PM and lasted about half an hour. The result was three torpedo hits and one very near miss, along with bomb damage to a destroyer and several targets on shore. The Italians fired off thousands of rounds of AA fire, but only downed one plane, that of Lt. Commander N. W. Williamson, the first-wave commander. Williamson and his observer, Lt. N. J. Scarlett, survived their plunge into the harbor and became prisoners of war.

The second wave of nine planes launched at 9:30 pm. A collision on the flight deck forced one plane to be scrubbed. The eight aircraft of the second wave arrived over the target at around midnight, and followed the same attack plan: flares dropped to illuminate the target, torpedo planes to attack battleships, bombers to go for targets of opportunity. Of the five torpedo planes, one was shot down, its crew killed; two missed, and two obtained hits on battleships. Bombers hit a cruiser and a destroyer, but the bombs did not detonate. More damage was done to shore facilities. Seven planes successfully returned to the carrier.

Italians recover a Fairey Swordfish from the sea after being shot down in the Battle of Taranto. Archivio Centrale dello Stato.

Damage Assessment

As a result, the final tally was three hits to Littorio, the newest and best of the six battleships in the harbor that night; one hit each to Conte di Cavour and Caio Duilio; minor damage to cruiser Trento and destroyers Librecio and Passagno; a destroyed seaplane hangar; and a heavily damaged oil storage depot. Illustrious lingered near the launch point with the idea of repeating the attack the next night. But bad weather and good photos verifying the damage convinced Admiral Cunningham to call it a day and head for home.

One of the pilots – all of whom were deeply impressed by the volume of AA fire – expressed his opinion of a repeat attack, saying, “They only asked the Light Brigade to do it once!”

Background on LCDR Opie

How did Opie end up aboard Illustrious? Officially, he was an Assistant Naval Attache to the American Embassy in London. The US Navy had been reluctant to exchange information with the Royal Navy. But the success of the German attack on France convinced the CNO that some people better get over there – fast – to learn what could be learned from the British. Opie had been suddenly pulled away from his duty as Gunnery Officer aboard USS Philadelphia in May, brought to Washington for a brief three-day indoctrination, and then booked aboard a civilian liner sailing from a Canadian port for London.

He traveled in civilian clothes, probably from a sense on the part of his superiors that his mission violated the Neutrality Act. Arriving in London on June 11, he almost immediately began going aboard British warships on active operations. In August, he embarked in Illustrious and went with her to her duty station with the Med Fleet. He was called a “neutral observer,” and was the first of many that would go over to England in 1940 to learn from the Royal Navy the lessons of combat. Once with the Med Fleet, he sailed in ships of all types, including a cruiser torpedoed by Italian aircraft. He wrote frequent and lengthy reports of his observations.

Opportunity for Lessons Learned Missed

Opie’s Taranto report arrived in Washington in January of 1941, and the delay seems to have lessened its impact. Back in November, CNO Harold Stark had been hot for more information. The Battle of Taranto was the page one story in the November 14 New York Times. By January, though, the US Navy had convinced itself that torpedoes would only run in deep (75 feet) water and sent this message out to the Fleet. Opie’s report, and those of other observers, that the Royal Navy felt that its torpedoes could successfully run in water as shallow as 24 feet seems to have been missed.

Although he asked to be sent to Hawaii to share the “lessons learned,” Opie returned in April to a desk job in Washington. His lecture to the Navy’s General Board covered other aspects of the attack. No one seems to have asked him about the depth of water issue. Interestingly, one of his lessons learned was that ships might be safer from aerial attack if they were at sea, rather than in a harbor. No one followed up on this idea, either. In September, Opie took over as CO of USS Roe, a destroyer on Atlantic duty. On December 7, Roe was docked at Hvalfjordur, Iceland’s major port.

Further Reading

For additional details on this event, take a look at my book, The Raid, The Observer, The Aftermath, which can be purchased above.

A Convinced Japan

The Battle of Taranto demonstrated the power of carrier-based planes. Striking from ‘over the horizon,’ such aircraft could surprise land-based targets and ships thought to be safe in their harbors. As aircraft became faster and better armed, this threat would only increase. The Royal Navy made this point with one carrier and twenty planes. The Japanese Navy would dramatically emphasize it when they attacked with 6 carriers flying 350 planes. The Japanese sent an attache from Berlin to Taranto in the wake of the attack to consult with the Italians and observe the damage.

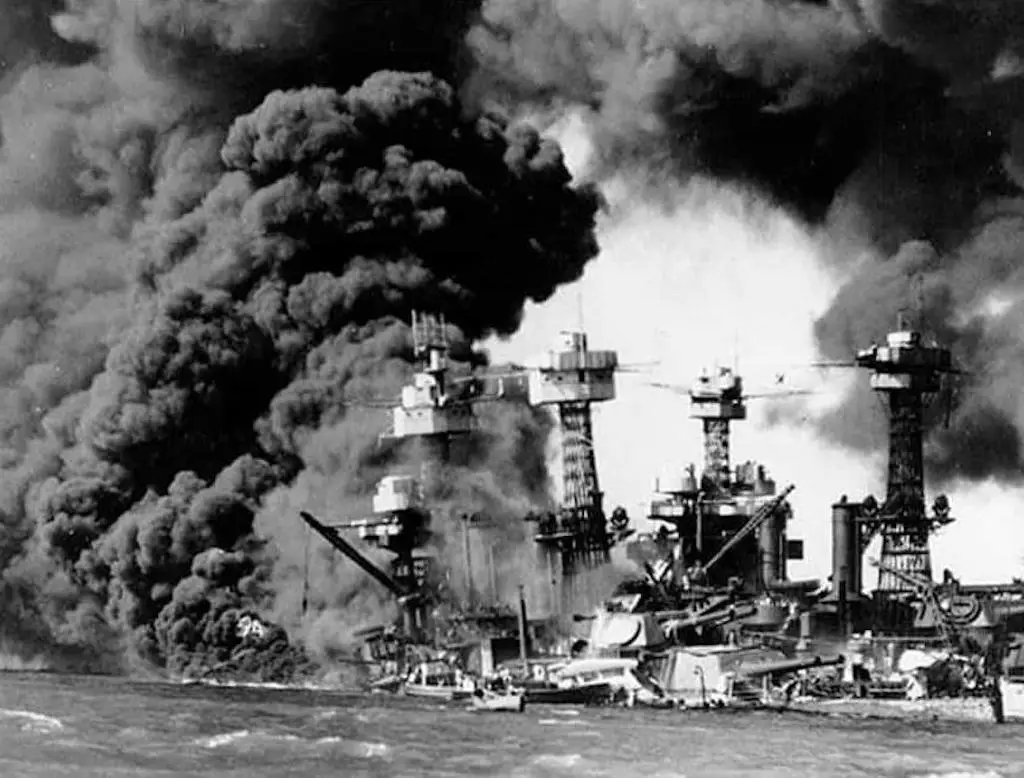

USS West Virginia and USS Tennessee burn following the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. | REUTERS/KYODO

Later, in May of 1941, a full-fledged naval mission to Italy would visit Taranto and engage in lengthy talks with the Italian Navy about the attack. The Japanese adopted the Italian method of preventing air-launched torpedoes from diving too far: that of attaching wooden fins to the torpedo to break its dive. They worked out the details in extensive testing conducted through the summer and fall of 1941. However, it seems likely that the idea came from the mission to Italy. Taranto did little to influence Admiral Yamamoto. He had already convinced himself that attacking Pearl Harbor was feasible, except perhaps to reinforce this belief.