The Montecuccoli class gave birth to the second and better light cruiser generation of the Italian navy. These ships experienced quite a lot of action during WW2.

Designing the ships

By 1930, the Regia Marina was in the process of renovating its entire cruiser compartment, the Trento class heavy cruisers had entered service in 1928/1929 while the new Zara class and the early Condottieri types (Giussano and Cadorna classes) were about to become operational.

The navy engineers were already studying improvements to the light cruiser designs since the first Condottieri ships suffered from stability issues and lacked decent protection. We should remember that these ships were designed to harass French maritime sea lanes in the western Mediterranean in a probable future war. Speed was thus the focus but the very limited protection of these ships led to reconsider the armor issue on the future light cruisers.

In 1931, the Regia Marina laid down two brand new ships, named Raimondo Montecuccoli and Muzio Attendolo. Their standard displacement increased by around 2,000 tons compared to the previous Cadorna class. The length increased to 182 meters (from 169) and the width to 16,6 meters (from 15,5). The armament remained the same, centred on 8x152mm guns (model 1926) while the superstructures were reduced in size. In particular, the conning tower assumed the recognizable conic (frustum) shape that will later characterize the subsequent classes of light cruisers. The placement of the funnels and the seaplane catapult was similar to the Cadornas, consolidating a well-balanced design choice.

The major improvement came with increased protection. By taking the Cadorna class as a comparison, the horizontal protection (the deck) increased from 20 to 30mm while the vertical protection increased from 24 mm to a composite armor made by a main 60mm thick piece of armor, coupled with an anti-shrapnel layer of 25mm. Protection over the gun turrets increased from 23mm to 70mm while the conning tower from 40mm to 100mm.

Ship profile

Interwar years

With the Montecuccoli class, the Regia Marina had finally found a balanced design for its light cruiser line. These were still very fast ships, able to reach 35-36 knots, but also capable to engage in a fight and sustaining hits. The experience of WW2 will widely prove it. Their design convinced the Regia Marina to later laid down the other two ships with some improved features, giving birth to the Duca D’Aosta class, very slightly slower but better protected.

Montecuccoli and Muzio Attendolo entered service in 1935 and have a relatively active careers in the prewar year. In particular, the Montecuccoli made a famous voyage in 1937 to the far east. The mission was to safeguard Italian interests in China after the start of the second Sino-Japanese war. The Italians, in fact, possessed the concession of Tianjin (since 1901).

During the service in the far east, the ship also visited Japan and Australia, before returning to Italy in December 1938.

Montecuccoli in Shanghai (1937)

Wartime service

When Italy entered World War Two, Montecuccoli and Attendolo, together with the Duca d’Aosta and Eugenio di Savoia, formed the VII cruiser division, commanded by Admiral Luigi Sansonetti. The division took part in the battle off Calabria but did not play an active role in the clash, navigating behind the battleships Cavour and Cesare.

After that event, and for the rest of the war, the two cruisers were employed in a variety of roles, such as mine laying, convoy escort, searching for the enemy and even transport.

In December 1940, the Montecuccoli, together with the Eugenio di Savoia, bombarded Greek army positions in the area of Lukova, while the Attendolo transported three battalions of black shirts to Albania in the following days.

Convoy escort and patrolling missions continued for the whole of 1941, culminating with the participation in Operation M.42, a huge effort of the Regia Marina to end the supply crisis of late 1941. The crisis originated with the deployment of Force K in Malta, a small force of destroyers and light cruisers able to effectively fight at night and locate Italian convoys in the night, thanks also to the availability of radar on ships and aircraft.

Operation M.42 saw the participation of four battleships and several cruisers, including the VII division under Admiral De Courten. The division sailed together with the battleship Duilio and safely escorted the convoy to Tripoli. The indirect escort, with battleships and cruisers, engaged British warships in the short-lived clash that took the name of First Battle of Sirte.

Montecuccoli and Attendolo relentlessly took part in other escorting operations in the first half of 1942. In June, a large allied effort to resupply Malta was launched, this took the shape of two twin operations named Harpoon and Vigorous. The Attendolo was in drydock for repairs and at that moment only the Montecuccoli and the Eugenio di Savoia formed the VII cruiser division, commanded by Admiral Da Zara. The division, escorted by some destroyers, was tasked with intercepting the enemy company in its final approach to Malta.

In the early hours of the 15th of June, Da Zara’s warships intercepted them near the island of Pantelleria. The Italian destroyers Vivaldi and the slower Malocello attacked the merchant ships while the rest of Da Zara’s forces engaged the escort.

Outgunned by the enemy, the British started to lay down smoke screens to protect the transport ships. They then headed southwards. However, the Italians managed to hit the cruiser Cairo and two British destroyers. The Vivaldi received a hit in the engine compartment and became immobilized. It was saved by the Malocello, which laid a smokescreen around the sistership and repealed the enemy attacks.

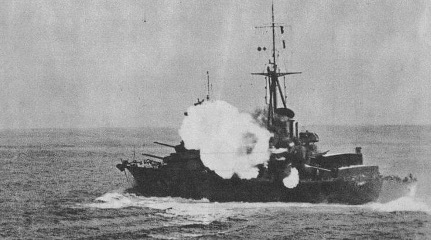

In the confusion of the battle, the merchant ships became distanced from the escort. Italian and German aircraft attacked them. The oil tanker Kentucky caught fire and was later finished off by the Montecuccoli. The merchant ships Burdwan and Chant also sank.

The combined firepower of Montecuccoli and Eugenio di Savoia crippled HMS Bedouin. An SM.79 Sparviero Torpedo Bomber finished her off.

After the battle, Hardy decided to continue his run to Malta with the surviving two merchant ships and escorts. Da Zara could not immediately pursue the enemy because of a minefield he had to circumvent. Only two transports arrived in Malta on 17 June 1942. The other four merchant ships sank or had been damaged by Italian mines. A detailed account of the battle can be found here.

The battle of Pantelleria

After Pantellaria, there were no more relevant surface actions, the deteriorating strategic position of the Axis and the little fuel reserves limited the action of cruisers and battleships.

In August, a similar interception was meant to take place, this time against Operation Pedestal, but the ships were recalled for the absence of sufficient air cover. On the way back, a torpedo launched by HMS Unbroken ripped off the bow of the Attendolo, which managed to reach Naples to undergo repairs.

The Attendolo was eventually lost in December 1942 during the bombardment of Naples, when she received several bomb hits and capsized. The shipwreck was refloated after the war and scrapped.

Epilogue

The Montecuccoli had instead a longer career. After the armistice between Italy and the allies, it sailed to Malta with the bulk of the Italian fleet, during the voyage the formation was attacked by German bombers that sunk the battleship Roma.

After reaching Malta, the Montecuccoli began a two-year-long period of “co-belligerence” where she supported allies in transport and training operations. After the end of WW2, the ship entered service with the post-war navy (Marina Militare) and remained in service until 1964.

Sources

Giorgerini, G., & Nani, A. (2017). Gli Incrociatori Italiani 1861-1975 (Ristampa IV edizione). Roma: USMM.

Giorgernini, G. (2001). La Guerra Italiana sul mare, La marina tra vittoria e sconfitta 1940-1943.

O’Hara, V. P. (2022). Lotta per il Mare di Mezzo. Roma: Ufficio Storico della Marina Militare.

Stille, M. (2018). Italian cruisers of World War Two. Osprey .