Immediately after the Cunningham-De Courten agreement, signed on the 23rd of September 1943, the Italian navy began closer cooperation with the Allied navies, involving all its ships, excluding the battleships. In September alone, Italian naval units managed to save around 22.000 scattered men of the Italian army, whose units had been destroyed by the Germans in the days following the armistice.

Naval operations

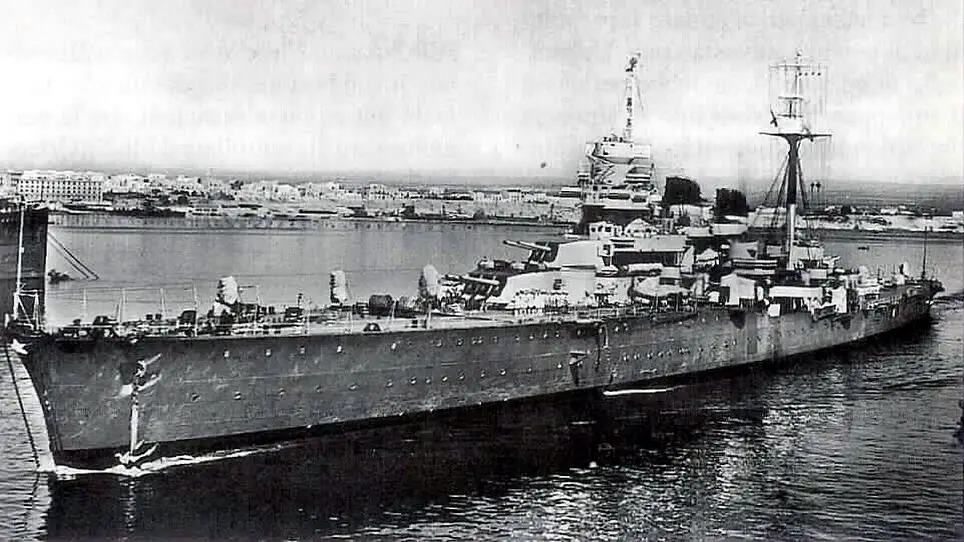

On the 27th of October 1943, the cruisers Duca d’Aosta and Duca degli Abruzzi left Taranto for a deployment in the Southern Atlantic. They reached the base of Freetown on the 13th of November and they began a series of surveillance cruises to stop any German surface raider or blockade runners. Under the command of Admiral Biancheri, they remained in this post until March 1944 when they were ordered to return to Italy.

Back in the Mediterranean, Italian destroyers, torpedo boats and corvettes were constantly engaged in escorting convoys aimed at resupplying the allied forces in Italy and the civilian population. A total of 1.525 were escorted, also accounting for the transfer of 317.000 men (Allied troops and Italians).

Figure 1 Cruiser Duca degli Abruzzi

Smaller units like M.A.S. boats and submarines were relentlessly used to land commandos or observers behind the enemy lines for sabotage missions, establishing clandestine radio stations or linking up with resistance fighters.

In early 1944, American personnel were transported to the islands of the archipelago before the coast of Tuscany, they had to set observation posts to monitor the German coastal traffic aimed at reinforcing the troops fighting at Anzio against the allied beachhead.

Special naval operations were also carried out in cooperation with the Royal Navy, which were separately described in this article.

A small number of submarines operated with the American and British surface units in Anti Submarine Warfare training operations.

Ships to the USSR?

In March 1944 a BBC radio broadcast reported the alleged words of President Roosevelt that a share of the Italian fleet would have been transferred to the Soviet Union. This news came like a flash in the dark and many of the Allied officials liaising with the Italians saw this as completely unexpected. Admiral De Courten (Minister of the Navy) was determined to clear the doubts and uncertainties, he was also equally determined to order the scuttle of the fleet if the Allies would have followed this path.

Figure 2 Admiral De Courten

In the following days, new clarifications came from Churchill and Roosevelt, the latter explained that this unfortunate situation was due to a misunderstanding of his words from the journalists.

The British Admiral McGrigor wrote a letter to De Courten explaining that during the Theran conference, the Soviets had indeed claimed the right to obtain a portion of the Italian fleet as a war prize. For the moment, since the Italian navy was helping the US and British navy, the two Western powers would have transferred some of their naval units to the Soviets, to supplement their needs (like the Battleship Royal Sovereign and the cruiser Milwaukee).

With this letter and official Allied reassurances, the Italian authorities were satisfied and an unnecessary crisis in the Western field was avoided.

The Resistance in Rome

After the armistice, thousands of men of the Italian armed forces remained scattered in the German-occupied territories. Soon they began to gather and set up groups of resistance fighters. On many occasions, they joined forces with civilians in partisan formations.

In Rome, men of the Italian navy under the leadership of Admiral Emilio Ferreri, formed a clandestine organization (Fronte Clandestino della Marina) that gathered between 200 and 300 men. They developed three types of activities:

Provide aid of any kind to their families and those of other former military personnel.

Plan and execute Sabotage and counter-sabotage missions.

Gather and provide intelligence to the allied forces (in particular the American 5th Army).

The intelligence activity was conducted by a small group of men led by Admiral Franco Maugeri, former head of the Secret Service of the Italian Navy. They set up clandestine radio posts and reported to the Americans any significant information regarding the movements of German troops. This stream of information was precious in the months of intense fighting in the Cassino area and at the Anzio beachhead.

In this period, they also managed to spy on the activities of Prince Borghese’s Xa M.A.S., launching attacks against the allied shipping near Anzio using small surface attack crafts.

The San Marco Regiment

The bulk of the Italian marines of the San Marco regiment had been lost with the surrender of Axis forces back in May 1943.

Only the newly forming “Caorle” battalion, the special NP battalion (paratroopers and swimmers) and a company guarding the Naval Staff HQ were available in Italy. After the armistice, these units were scattered or disbanded but most of the men managed to reach southern Italy and formed the basis for the reborn San Marco regiment.

Two new battalions were formed, bearing the historical names “Bafile” and “Grado“. These units joined the reformed forces of the Italian army that fought alongside the British and American armies along the peninsula.

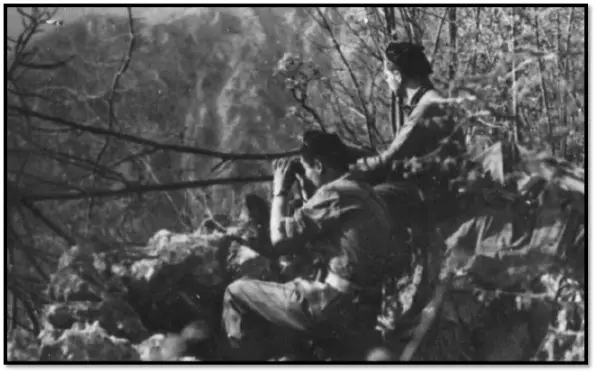

Figure 3 Men of the San Marco Regiment at Cassino

Noteworthy, the San Marco regiment fought on the Cassino front in early 1944 while in 1945 it liberated Venice together with British commandos.

A few numbers

According to the official statistics, the personnel of the Italian navy suffered 4.766 killed, the Germans or Italian Fascists executed 431. During the co-belligerency period. 7.000 men of the Navy joined partisan formations and 846 of them perished.

Sources

Fioravanzo, G. (1971). La Marina dall’8 settembre 1943 alla fine del conflitto. USMM.

Pasqualini, M. G. (2023). 8 Settembre 1943-25 aprile 1945 – La Resistenza dei Militari Italiani: un lungo percorso sino alla vittoria finale.

USMM, a cura di M. Gabriele (1993), Le memorie dell’Ammiraglio De Courten, 1943-1946

USMM, a cura di G. Manzari (2015), La partecipazione della Marina alla guerra di liberazione (8 settembre 1943-15 settembre 1945)