Italian navy ships entered World War two with their distinct light grey painting. As in the case of all other navies, Camouflage schemes started to be tested, up until widespread adoption in 1942.

Great war experience

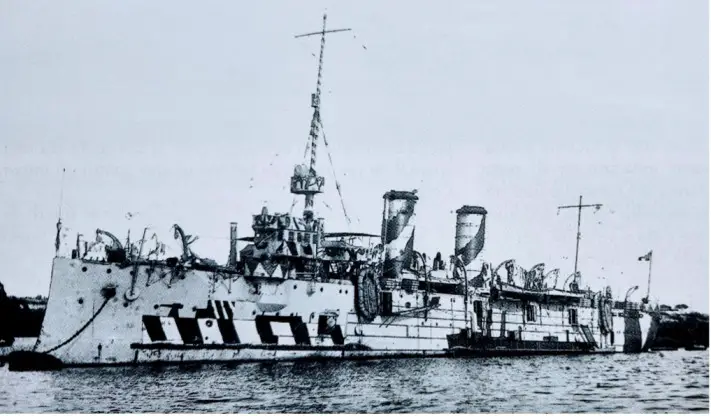

The Italian Navy (Regia Marina) ventured into the field of naval camouflage only towards the end of the Great War. A sort of dazzle painting was applied to a pre-dreadnought battleship, a few scout cruisers, and destroyers. The idea behind the application of such camouflage was to make it difficult for the enemy the estimate the distance, thus jeopardizing fire direction. A peculiar scheme was applied to the transport ship Cortellazzo, where the silhouette of two smaller warships was painted on the sides. The war soon came to an end and with these early camouflage schemes proving to be quite unsatisfactory, the Regia Marina abandoned, for the moment, the art of naval camouflage.

Figure 1 The troop transport ship Cortellazzo

Entering WW2

When Italy entered World War Two in June 1940, all the Regia Marina warships were painted with a light ash grey colour. After the friendly fire incidents occurred during the Battle off Calabria, where Italian aircraft bombed Italian ships (with no hits), the decision was taken to adopt clear markings signaling the nationality of the ships. Thus, the Regia Marina adopted the white and red stripes painted over the final tip of the bow deck. The stripes were higher on the left and usually extended up to the first barbette or gun emplacement. This measure was adopted on basically all warships, from battleships to smaller vessels.

In August 1940, the navy high command tasked Major Luigi Petrillo (of the Naval Engineering Corp) to study the optimal solution for a new camouflage to be adopted by all warships. Petrillo’s team worked on two distinct options, the actual camouflage of a ship, aimed at disguising the shape, direction, and speed and on the other side the mimetic, the overall reduction of the visibility of the ship. The first path was deemed to be more practical, and studies continued for the following months until the first concrete proposals came forward in January 1941.

In search for the optimal camouflage

The first solution was the adoption of the so-called fishbone scheme. The ship was to be painted in a darker grey with superimposed triangles painted with a very light shade of yellow-green. The second solution saw the adoption of a dazzle pattern with splotches of dark and light grey. The first scheme was painted on the Duca d’Aosta light cruiser while the second was on the heavy cruiser Fiume. Fiume was lost during the battle of Cape Matapan, less than a month after receiving the new camouflage. In fact, only two pictures of the ship exist where we can partially see this camouflage.

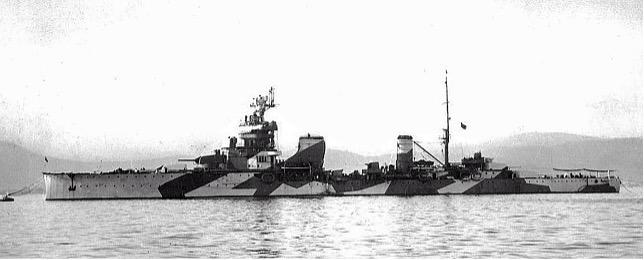

The fishbone scheme was painted on battleship Littorio, Duilio and Vittorio Veneto. In the same period, other tests were conducted on destroyers and auxiliary units. These were in fact all tests since Petrillo’s work had been rushed and the navy decided to test all these variants directly at sea.

Figure 2 Vittorio Veneto with the Fishbone scheme

The fishbone scheme proved to be not so satisfactory since it did not reach the expected disruption effect beyond 5,000-6,000 meters.

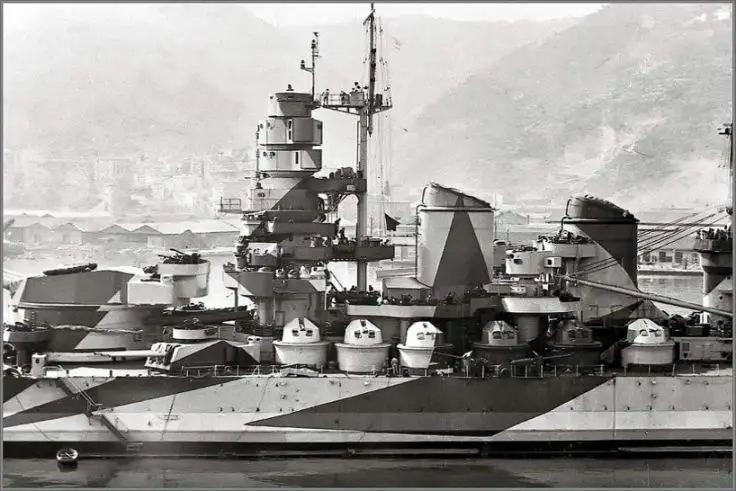

With Petrillo’s team disbanded due to service requirements, the navy approached the Austrian painter Rudolf Claudus, an admirer of the Regia Marina who had moved to Italy in the previous decades. The painter conceived a peculiar camouflage scheme which included abstract forms, one clearly resembling a saw and this one became known as the Claudus scheme. Battleships Andrea Doria, Cesare, Cavour, the destroyer Ascari and the cruisers Attendolo and Garibaldi received this new painting.

Figure 3 Andrea Doria with the Claudus Scheme

This one proved to be slightly better than the fishbone one but still not satisfactory enough.

The turning point came in October 1941, when a new camouflage scheme was painted on the light cruiser Giovanni delle Bande Nere. This was a dazzling scheme with straight-edged dark grey bands on a light grey background. This scheme proved to be quite effective and led to the ‘standard’ schemes applied to most Italian warships from early 1942 onwards.

Figure 4 Cruiser Garibaldi with the Claudus scheme

The positive results with the Bande Nere scheme, led to the issue of a brand-new standard for naval camouflage, issued in late December 1941. This one essentially required only two colours, light ash grey and dark grey. The irregular lines in dark grey had to be painted avoiding vertical and horizontal trails. This general standard led to the reality that each ship had its own typical pattern, which however respected the general rules.

Figure 5 The camouflage scheme adopted on the Bande Nere

A few ships remained the exception, since they conserved slightly different camouflage, the most notable example being the Battleship Littorio, which after the first fishbone scheme adopted the standard camouflage colours but with splotches instead of irregular lines.

Figure 6 Destroyer Pancaldo withe new standard camouflage

Figure 7 Standard camouflage scheme of the Vittorio Veneto

After the armistice of September 1943, the Regia Marina began its cooperation with the Allied navies and thus a new camouflage scheme was adopted, more similar to that one in use by the Royal Navy and US Navy. The hull was painted in dark grey and the superstructures light ash grey. This camouflage remained in use for some years after the end of the war.

Submarines and merchant ships

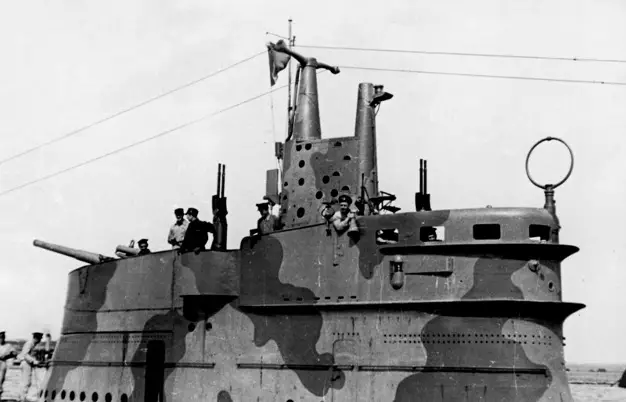

The pre-war standard paint of Italian submarines was dark grey, the reason being that since Mediterranean waters tended to be very transparent, a “darker” submarine would have been less visible when submerged at depths of 20-40 meters.

However, this color scheme proved to be ineffective since it made the submarines more easily spottable from air and surface units when they navigated. To solve the problem, from the summer of 1940, experiments on new camouflage schemes commenced in the bases of La Spezia and Taranto.

Figure 8 Conning tower of the submarine Zoea (Risolo collection)

Towards the end of the year, a new adequate camouflage solution emerged and became the new standard from early 1941. Submarines had to be painted in lighter grey (tending to light blue) with irregular brown splotches. This remained the general standard for the rest of the war, with minor updates and specifications coming towards the end of the year.

This camouflage was adopted by all the submarines operating in the Mediterranean, while those operating in the Atlantic kept their pre-war painting scheme (with few exceptions). After the armistice, the surviving submarines of the Regia Marina transitioned towards a uniform color scheme, in some cases resembling that of one of US Navy submarines.

Sources

Brescia M. (2012), Mussolini’s Navy, Seaforth publishing

Bagnasco E., Brescia M. (2017) Il Camouflage delle navi italiane 1940-1945, Edizioni STORIA MILITARE