Armistice and aftermath

On the evening of the 8th of September 1943, the announcement of the armistice between Italy and the Allies caught almost every Italian by surprise, the new situation was faced in many different ways by the hundreds of military commands dispersed in Italy and abroad.

In La Spezia, the commander of the 10° M.A.S. flotilla (the unit operating with human torpedoes, explosive motorboats and commando frogmen), Prince Junio Valerio Borghese listened to the radio broadcast and then spent the following hours searching for more information. His unit maintained cohesion and remained in its barracks in La Spezia. On the morning of the 9th of September, Borghese sent a message to the local German commanders and pledged that his men would have never undertaken any offensive actions against them.

Borghese did not receive well the announcement of the armistice, he was determined to keep on fighting the Anglo-Americans. According to him, for reasons linked to military honour and pride, not for political reasons.

He later gathered the 400 men under his command and offered them the choice of staying and continuing the fight alongside the Germans or going home. According to Borghese’s personal notes, only 10 men decided to stay with him. In the days that followed, Borghese entertained negotiations with the German military commands and finally, on the 14th of September, he stroke a deal with the Corvette Capitain Max Berninghaus, head of the Kriegsmarine command in the region. Through this agreement, the Germans recognized the Xa MAS flotilla (note the difference from 10° M.A.S. to Xa MAS) as an autonomous fighting unit of the Italian navy, with their own battle flag and commanded by Prince Borghese.

This deal, coupled with Borghese’s de facto mutiny from the Regia Marina and the legitimate Italian government, marked the end of any continuity between “his” Xa MAS flotilla and the 10° M.A.S.flottilla of the Regia Marina.

It is also interesting to note that the creation of this unit was preceded by 9 days the formation of the Italian Social Republic, the new puppet state installed by the Germans in central and northern Italy.

New volounters and tensions

In the weeks that followed, Borghese tried to re-organize his limited forces and put back together all the naval units available, a few MAS boats, midget submarines and motorboats. The flotilla was also joined by crews repatriating from the submarine base of Bordeaux.

Soon, hundreds of young volunteers joined the ranks of the Xa MAS flotilla but they were in real surplus with respect to the very limited naval assets available. Borghese decided then to organize infantry formations organized in battalions, the first one being the “Barbarigo” battalion. The winter of 1943-1944 was a period of training and re-armament, made difficult also by the German resistance at unlocking the supply of light arms and artillery, previously captured from Italian units in the days after the armistice.

Prince Borghese inspecting his men

Soldiers of the Xa MAS with their battle flag

Young soldiers of the Xa MAS

An event that is worthy to mention, is the arrest of Prince Borghese in January 1944 in Brescia, at the hands of the Italian Social Republic. He was accused of plotting a coup against Mussolini. This was clearly an excuse, the main reason behind it was perhaps the “unacceptable” liberty of action enjoyed by Borghese, something that many high-ranking officers in Mussolini’s ruling elite did not like. This situation sparked a rebellion of the Xa MAS whose men threatened to march on Brescia to liberate Borghese. This internal crisis of the Italian puppet state was settled in the space of a week, when the Germans sided with Borghese, who was liberated soon after.

Operations and war crimes

In March 1944, the “Barbarigo” battalion, with 650 men strong, was deployed against the American forces near Anzio, fighting bravely, but also suffering heavy losses.

Between May and July 1944, the Xa M.A.S became a true infantry division (Divisione fanteria di Marina Xa), thanks to the presence of a few thousand volunteers and the availability of new weapons, unlocked by the Germans. Two infantry and one artillery regiments, together with a variety of autonomous battalions and companies created the bulk of Borghese’s personal army.

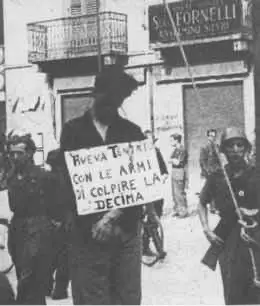

In 1944, the growing Xa MAS became engaged in the de facto civil war with the Italian partisan movement, especially in the Piedmont region (northwest of Italy). Initially, determined to fight just the Anglo-Americans, the cooperation of the Xa MAS with the occupying German forces, and the growing partisan activity, made the clash inevitable. In this context, several units of the Xa MAS became protagonists of retaliation actions against civilians, torture and ferocious executions of partisans.

Italian partisan executed by the Xa MAS

From October 1944, Borghese moved most of his men to Gorizia, in the North-East of Italy. His aim was to fend off the advance of the Yugoslav communist forces led by Marshall Tito. In his memoirs, Borghese wrote that by that time, he was expecting the defeat of the German forces all over Europe, and thus he wanted to shield the Italian land from the advance of the Yugoslav forces.

Between the end of 1944 and January 1945, the Xa MAS clashed repeatedly with the Yugoslavs, one of the most notorious episodes being the Battle of Tarnova (located in nowadays Slovenia) where the “Fulmine” battalion, 300 men strong, fought surrounded against 2000 Yugoslav partisans until the arrival of mixed German and Italian reinforcements which allowed the Fulmine to withdraw.

At the end of January, the Germans ordered the withdrawal of the Xa MAS from the Yugoslav front. Few units like the “Lupo” and “Nuotatori Paracadustisti” battalions saw action along the Gothic line on the Apennines between Tuscany and Emilia Romagna, while the rest of the division remained in the Veneto region.

Secret contacts and end of the war

In the last six months of the war, Borghese and the Xa MAS entered into secret contacts with the Regia Marina (operating in the south), Italian partisans and American intelligence officers. The reason was the threat posed by the advancing communist armies advancing from the East, nobody in the allied camp wanted to see such eventuality in the final stages of the war. In addition, there were fears of a possible large-scale German sabotage of the remaining factories and vital infrastructures in northern Italy. These two scenarios had to be prevented, in order to secure Italy’s position in the post-war order.

In March 1945, one of the heroes of the Alexandria raid, Antonio Marceglia, crossed the enemy lines to make contact with Borghese directly, urging him to deploy his forces against Tito’s forces until the arrival of the allied armies from the south. However, the depletion of the Xa MAS battalions precluded any further commitment to the Italian eastern front. Regarding the anti-sabotage activity, Borghese’s men accepted to participate, but the Germans ultimately gave up on implementing any major sabotage actions and negotiated the surrender of their forces in Italy.

The units of the Xa MAS, scattered around northern Italy saw actions until the end of the war, against partisans and allied forces alike. On the 26th of April, Prince Borghese officially disbanded the division and his command in Milan. Here, he was taken in custody by an American OSS agent, James Angleton and an officer of the Regia Marina, Carlo Resio, who brought him to safety, away from an eventual popular trial and certain execution.

An Italian tribunal found him guilty of collaboration with the German occupiers and sentenced him to life imprisonment, subsequently reduced to 12 years. The Togliatti amnesty of 1949 made Borghese free again, allowing him to start a new life in postwar Italy.

The memory of the crimes of the Xa MAS and of their collaboration with the Germans, marked forever the name of this unit and of its commander, engaged in a terrible civil war that took away the lives of many innocents.

Sources

Giorgerini, G. (2007). Attacco dal mare, storia dei mezzi d’assalto della marina italiana.

R.P. (2014) La notte di Alessandria (Tomo VI)

Interview with James Angleton: https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/BORGHESE%2C%20JUNIO%20VALERIO_0040.pdf

Foglio senza Titolo, firmato da Borghese in data 15 gennaio 1944, conservato nell’Archivio Centrale di Stato. Segreteria particolare del Duce – Carteggio riservato R.S.I. – busta 73 – sottofascicolo 10 – allegato 1. AUSMM, R6, b. B II, fg.10

Relazione sulla missione eseguita nell’Italia occupata dal capitano G.N. Antonio Marceglia