Context

In the evening of the 8th of September 1943, Marshal Badoglio broadcasted via radio the announcement that Italy had signed an armistice with the Allies. Italian armed forces had to cease any hostility against the allies and were told to respond to “attacks from any other origin”. The reference to the Germans was crystal clear. The top hierarchies of the Army and Government had initiated negotiations with the allies already after the fall of Mussolini (25th July 1943) while publicly pledging to continue the war alongside the Germans, who never believed such pledges. Since August, General Mario Roatta (Army chief of staff) and General Vittorio Ambrosio (General chief of staff), had drafted the plan O.P.44, providing general guidelines for the armed forces to face a German reaction following the armistice declaration. The high secrecy around such a plan, known only by a handful of army commanders, and the absence of clear orders following the armistice announcement, ultimately led to the general demise of the Italian Army, in Italy and abroad.

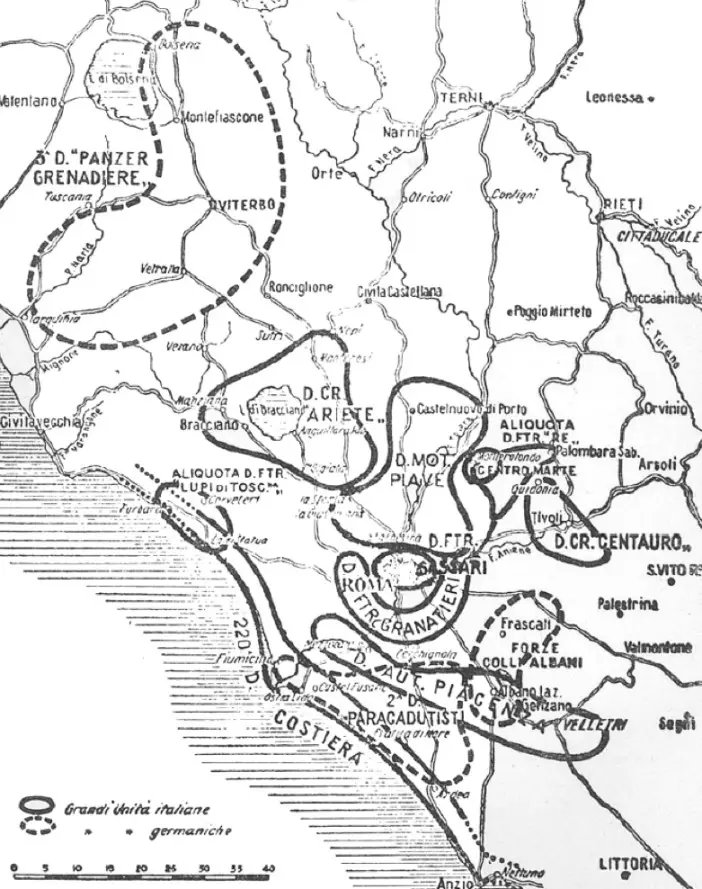

In August, intending to protect the capital, the King and the government from a German retaliation, the army leadership ordered the concentration of considerable forces around Rome. These forces were:

The armored division “Ariete II” deployed north near the Bracciano lake and guarding the road to Rome. The Ariete II had around 176 armored vehicles, including M15/42 tanks, AB41 armored cars and Semovente M41/M42.

The armored division “Centauro II” deployed in reserve east of Rome.

The motorized division “Piave” guarding the North-North-West perimeter of Rome

The infantry division “Granatieri di Sardegna” guarding the South South-West perimeter around Rome.

The infantry division “Sassari” guarding the inner city.

The infantry division “Piacenza” and the costal 220° and 221° divisions guarding the coastline.

In total, the Italians could rely on 80.000 men and more than 300 armoured vehicles. The German forces available in the area were the 3rd Panzer grenadier division, deployed north of Lake Bracciano, and the 2nd Fallschirmjäger division deployed south of Ostia, near the coast.

The fights on the 8-9 September

For a short time, the King and the government foolishly hoped in a peaceful withdrawal of the Germans to the north, also in combination with the allied landings in Salerno. Soon they were proved wrong, already in the night of the 8th of September, the Fallschirmjäger division had occupied an important military deposit south of the Capital and had attacked the Piacenza division, caught in disorder, and left without clear orders. The Fallschirmjägers moved north and tried to force into surrender the division “Granatieri di Sardegna”. The commander of the Granatieri, Gioacchino Solinas, stubbornly refused and ordered to open fire on the Germans. Fights erupted all over the defensive positions held by the Granatieri in the early hours of the 9th, but the Italian resistance denied the Germans any further advance and the capture of the Magliana bridge, the southern gateway to Rome.

An artillery piece in the streets of Rome

To the north, near Lake Bracciano, the 3rd Panzergrenadier division advanced towards the positions held by the Ariete II. Near Monterosi, the 23-year-old second-lieutenant Ettore Rosso and his men of the Ariete combat engineers battalion had just begun placing mines and obstructions when the Germans arrived. They received an ultimatum, requesting them to clear the way within 15 minutes, Ettore Rosso with the help of four volunteers (Pietro Colombo, Augusto Zaccani, Gino Obici and Gelindo Trombini), moved their trucks loaded with mines to form a roadblock and opened fire on the advancing German armoured column. When Rosso realized that he could not stop the advancing column, he and his men blew up the vehicles loaded with explosives, sacrificing themselves to delay the enemy. The Germans suffered losses and were later repelled by the intervention of other Ariete units in the area, thus constituting the only armoured clash between Germans and Italians in the second world war.

Despite having temporarily stopped the Germans, the Government and Army leadership believed that Rome could not be held, and the priority was to grant the safety of the King, allowing him to escape south in Allied-controlled areas. This plan generated the order that ultimately compromised the defence of Rome, all the units had to converge on Tivoli (East of Rome) to protect the road to Pescara, the escape route of the King (and the Government).

The division “Granatieri di Sardegna”, which had resisted the fallschirmjager advance, started its withdrawal towards the city and fought rearguard actions against the Germans before reaching the perimeter of the City walls.

The fights on the 10 September

An Italian semovente defending San Paolo Gate

While negotiations for a ceasefire were ongoing, the Granatieri had established their new defences around San Paolo gate, joined also by detachments of the Sassari and Ariete II divisions. In the general confusion, with the highest military and political authority on the run, defensive actions were left in the hands of local commanders who bravely led their men in such a dire situation. At this point, also the civilian population joined the fight, armed with hand grenades and rifles they fought for the whole day side by side with the men of the Regio Esercito. The facts of the 10th of September are generally considered the first act of the Italian (civil) resistance against the Germans.

Epilogue

Civilians fighting near San Paolo gate

By 5pm the Germans, supported by armoured units, overrun the defences at San Paolo gate and, soon after, news came that the ceasefire had been signed. Guns went silent as the short-lived defence of Rome was over. The Italians had suffered around 1000 casualties, including 121 civilians (of these, 51 women). Rome remained under Nazi occupation until June 1944, during this period, men of disbanded army units and civilians from antifascists movements gave birth to clandestine groups carrying out sabotages and ambushes against the Germans.

Sources

Lattanzio, A. (2020, Dicembre). La battaglia per Roma 1943. Tratto da Primo Raggio: https://ilprimoraggio.wordpress.com/2020/12/02/la-battaglia-per-roma-settembre-1943/

Solinas, G. (1968). I Granatieri nella difesa di Roma. Società Italiana di Storia Militare.