The pinnacle in the evolution of Italian light cruisers develop in the interwar years

The pinnacle in the evolution of Italian light cruisers develop in the interwar years

Class Design

In the early 1930s, Italian naval designers had finally overcome the design issues that emerged in the first light cruisers of the Giussano and Cadorna classes. The Montecuccoli and Duca d’Aosta classes marked this turning point towards more balanced and capable warships of this kind. Following the design of the Duca d’Aosta class, new studies began on yet another improved version of these cruisers. The Duca Degli Abruzzi class cruisers were the final evolution of 10 years of cruiser designs and were truly formidable ships.

Their horizontal protection increased to 40mm, but the biggest improvement came in the vertical protection which increased to 100mm plus a 30mm decapping plate. For comparison, the former Duca d’Aosta class had only 70mm. This level of protection was by many considered almost equal to that of the Zara class heavy cruisers. In turn, the maximum speed decreased to 33 knots (from 36 of the Duca d’Aosta) but was still considered an excellent compromise. The secondary armament remained the same as all other Italian cruisers, based on the twin 100/47 complexes. Another innovation came in the main armament. All previous light cruisers were equipped with eight 152/53 guns, with each pair of guns installed in the same mounting. This meant that the guns had to be elevated and fired together. The cruisers of this class received instead received the modern 152/55 guns, with each barrel capable of an independent elevation. In addition, the number of weapons increased from eight to ten.

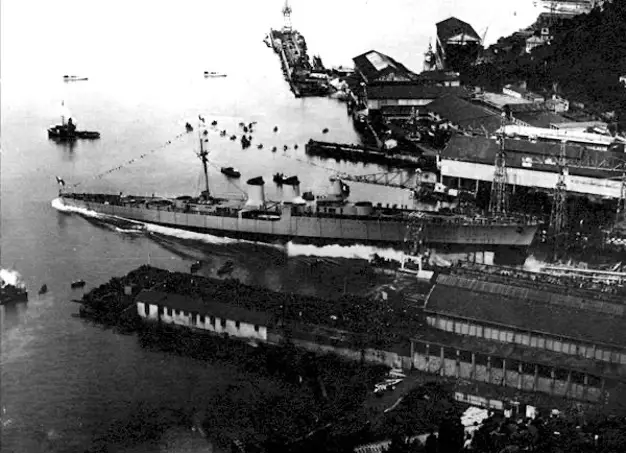

Two ships (Duca Degli Abruzzi and Garibaldi) were ordered in the naval programme of 1932-1933 and entered service in 1937, becoming fully effective in 1938.

Figure 1 Launch of the Duca Degli Abruzzi

Wartime service

Garibaldi and Abruzzi formed the 8th cruiser division and had a long and busy carrier. On the 9th of July 1940, they took part in the Battle of Calabria where they formed the vanguard of the Italian fleet. They exchanged fire with British cruisers in the opening phase of the battle and faced brilliantly a more numerous formation of enemy ships, later reinforced by the battleship HMS Warspite. The two ships participated also in Operation “Gaudo”, the Italian attempt to disrupt British convoys aimed at resupplying Greece. The operation ultimately ended with a brief clash off the island of Gavdos and the night action of Matapan, but the ships were not involved in the actual fights. For the rest of the war, they took part in various operations, aimed at intercepting British resupply missions destined for Malta but, above all, they served as indirect escorts to several axis convoys bound for Libya.

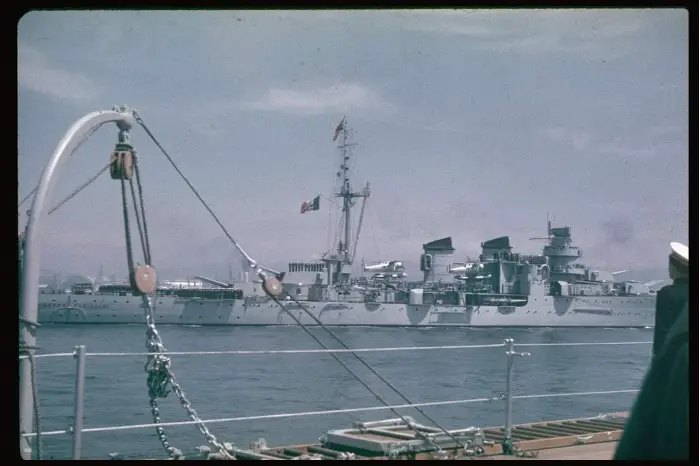

Figure 2 Garibaldi photographed in 1938

During one such mission, in July 1941, the Garibaldi received a torpedo hit. This time, the British submarine HMS Upholder scored a hit on the right side of the ship, below the forward turrets. 700 tons of water flooded the ship but its structural integrity was not compromised and the Garibaldi reached Naples proceeding at 10 knots.

In September 1941, the Abruzzi suffered a hit from a British torpedo bomber that struck the ship on the right side towards the stern and had the rudder disabled. However, the Abruzzi remained afloat and managed to reach a safe port ad undergo reparations.

In June 1942, the Abruzzi took part in the Regia Marina efforts aimed at countering Operation Vigorous, another convoy aimed at resupplying Malta. The presence of a strong Italian formation at sea forced the Mediterranean fleet to abort the mission.

With the strategic situation shifting heavily in favour of the Allies in October-November 1942, the ships saw fewer actions, especially due to fuel shortages and the presence of overwhelming allied forces. One last action was launched in August 1943, when Admiral Fioravanzo took the Garibaldi and the Duca d’Aosta to conduct a bombardment operation against the allied merchant ships in the harbour of Palermo, recently liberated by the Americans. Fioravanzo received reports that hinted at the presence of superior allied forces in the area and thus aborted the mission. He was criticized for his conduct but, after the war, further evidence confirmed his suspicions.

Figure 3 The 152/55 guns

Co-belligerence and post-war period

When Italy signed the armistice with the allies, the Abruzzi and Garibaldi sailed to Malta, together with the rest of the fleet. They will not be interned and, on the contrary, they carried out many support operations for the Allies. From November 1943 to February 1944, they were deployed in the Atlantic, carrying out patrols in search of German blockade runners. Later, they headed back to the Mediterranean and carried out transport and training missions. During a stop at Gibraltar, both units received a British-built radar device.

After the end of the war, Abruzzi and Garibaldi were kept by the re-born Italian Navy (Marina Militare) and took part in several NATO exercises in the early 1950s. They were later modernized, with Garibaldi undergoing a radical reconstruction process which turned it into the first missile-launching naval platform of the Italian navy.

Figure 4 The Garibaldi after its reconstruction

Sources

Fioravanzo, G. (1959). La Marina Italiana nella seconda guerra mondiale, Volume II La Guerra nel Mediterraneo: le azioni navali (Tomo 1). Roma: USMM.

Giorgerini, G., & Nani, A. (2017). Gli Incrociatori Italiani 1861-1975 (Ristampa IV edizione). Roma: USMM.

Giorgernini, G. (2001). La Guerra Italiana sul mare, La marina tra vittoria e sconfitta 1940-1943.