Invading Malta in 1940

Why did the Italians not occupy Malta in the summer of 1940? This is a quite popular question that is mirrored by statements like “the Italians failed to occupy Malta early in the war when it was undefended”. Such arguments can be easily found in books and documentaries about Italian participation in WW2.

On the other side, there are no detailed analyses on the feasibility of such an operation in the English language, while more attention has been given to the planned invasion of 1942. In this article, I will try to dispel some myths and explain why the capture of Malta in the summer of 1940 was essentially impossible for the Italian armed forces.

Prewar planning

Italian military planners had studied in the late 1930s the feasibility of transporting men and supplies to North Africa in the context of a war against France and the UK. The task was considered very difficult due to the balance of naval forces. Malta was identified as a huge potential threat to the Italian convoys, as a powerful surface force could be deployed there, together with numerous aircraft. The plan considered that an occupation of the island could solve the problem but acknowledged the difficulties of the operation, without going in much detail.

It was considered that a neutralization of the island through aerial bombardment was more convenient and less risky. After the outbreak of WW2, the Mediterranean fleet moved to Alexandria and no significant air units were placed in Malta. With the Italian entry into the war approaching, the Italian navy studied more in-depth the plan for the invasion of Malta. They concluded that it was a very risky endeavor with no great chances of success, and perhaps it was better to “let the war be decided elsewhere”. The following paragraphs will explain the elements that led the Italian planners to abandon the idea.

The terrain

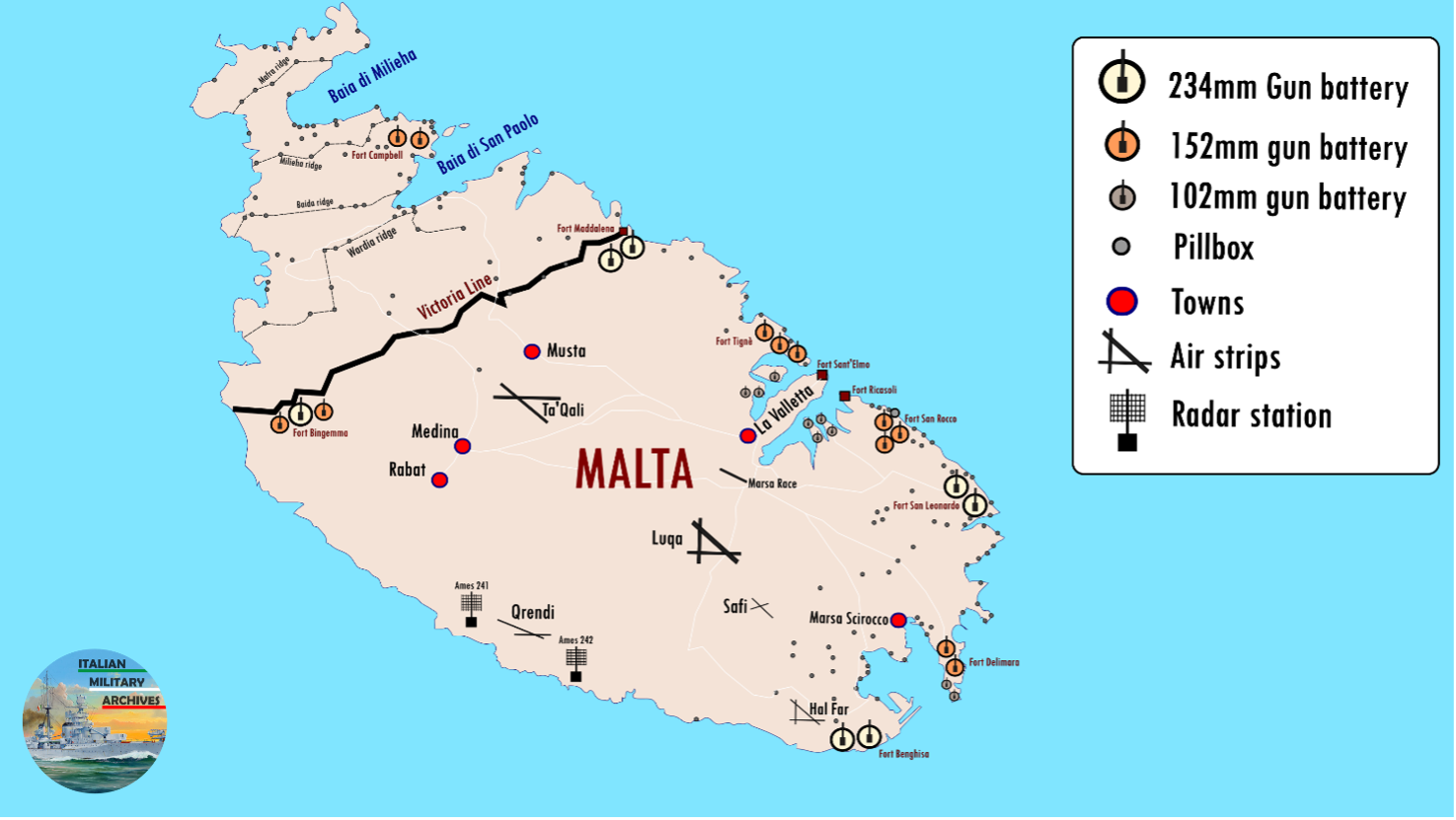

Any tourist that has the luck to visit this lovely island of Malta, will not fail to notice that almost the entire coastline is characterized by rocky reefs and cliffs, with only a handful of small beaches. The terrain is rocky and hilly in the northwestern part of the island. The two locations more suitable for landing a seaborne invasion force are the beaches of St. Paul Bay and Mellieha Bay. The first one is roughly 300 meters long and less than 900m is the second.

If such an invasion force is to land on such beaches, it will have to face an upward rocky terrain, with subsequent ridges and being subject to artillery fire. In fact, some miles to the southeast, the invasion force would have faced the Victoria Line, a series of defensive emplacements built in the 19th century. Surely obsolete for 20th century standards, but quite effective to repel infantry equipped with light weapons. In addition to the Victoria Line, many pillboxes had been built in large numbers from 1935, all around the island but in particular in the northwestern part.

Figure 1 Malta in 1940

Figure 2 Defensive emplacements of the Victoria Line

Figure 3 One of the many pillboxes on the Island

Figure 4 A piece of the Southern coast

Last but not least, an invasion force landing in the above-mentioned Bays and marching southwest, would have found nothing to live from (water and food), and all the supplies should have been landed on the beaches.

The Defenders

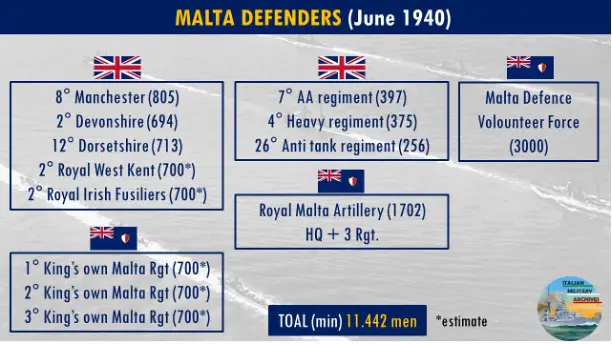

Looking at the forces that defended Malta in June 1940, the sources consulted allowed me to estimate (downward) around 11.442 men defending the island. This number does not count the Royal Navy and Royal Air Force personnel. Looking at the units defending Malta (see Figure 5 for the details), there were 5 fully equipped battalions of the British (standing) Army. The infantry force was supplemented by the raising of the King’s Own Malta Regiment, on three battalions. There was the Royal Malta Artillery regiment (1702 men), who manned most of the AA batteries and three units of the (British) Royal Artillery, manning the heavy coastal batteries, the anti-tank guns and part of the AA batteries. To complement these forces, there were around 3.000 men of the Malta Defence Volunteer Force. These were civilians equipped with firearms and rarely uniforms, who provided anti-paratrooper and observation patrols.

Regarding the air defence, the myth of the three Gloster Gladiators “Faith”, “Hope” and “Charity” is, of course, a myth, these names were made up later. As Douglas Austin writes, “Twelve Fleet Air Arm Sea Gladiators had been left at Kalafrana in packing cases when the aircraft carrier, HMS Glorious, sailed for Norwegian waters. He obtained Admiral Cunningham’s permission to assemble six of these, while the other six were used for spare parts”. In late June, the island was reinforced by the arrival of the 830° squadron of the Fleet Air Arm, flying Swordfish torpedo bombers. 12 Hurricanes flying from Tunisia arrived a few days after the war declaration of Italy, however, these aircraft were destined for Alexandria and only one remained in Malta until the arrival of more modern fighters in August.

The coastal defense was provided by seven 9.2-inch guns and around twelve 6-inch guns, their disposition can be seen in Figure 1. The island was also surrounded by roughly 1.000 naval mines, many of them defending the most likely landing places, like St. Paul’s and Melieha Bays.

Figure 5 Strenght of the Malta garrison

The Italian forces

Facing an 11.000-12.000 strong garrison, any reasonable war plan for an invasion of Malta would have required the transport of an invasion force of at least double the size. Italian planners in spring 1940 estimated it in 40.000 men, a number which considered the inevitable losses incurred in such operation. The problem was that transporting and landing such an invasion force was a though job.

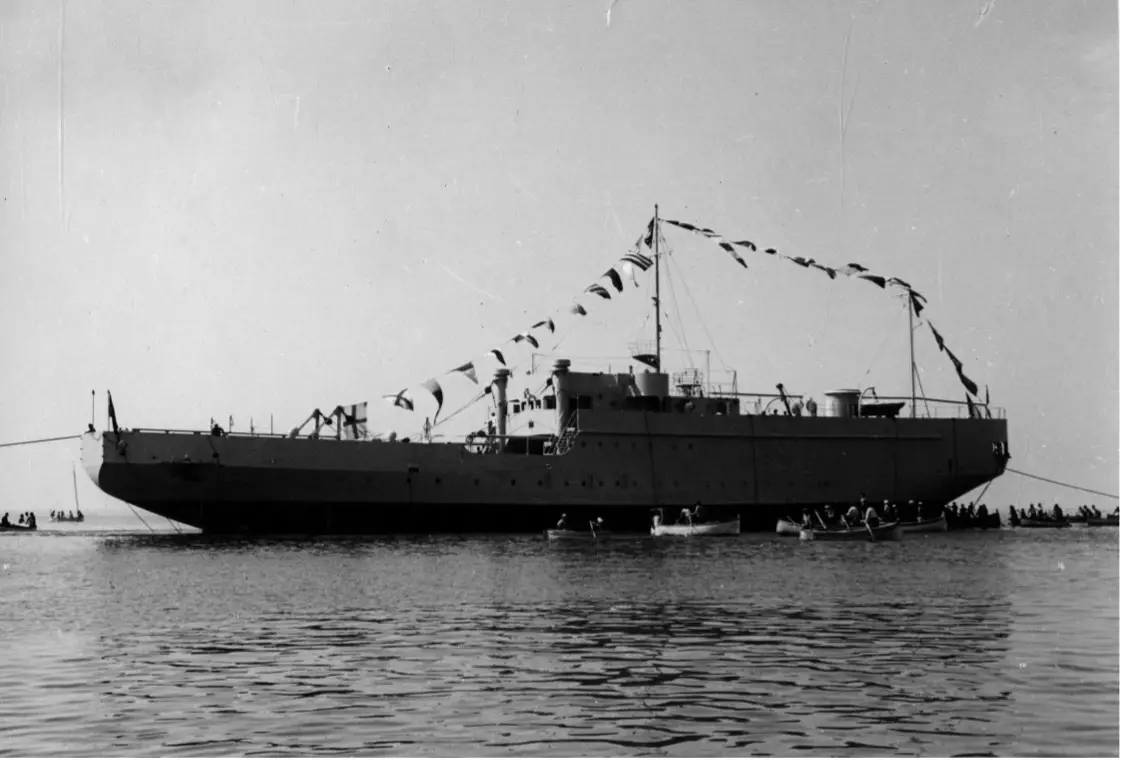

The Italian navy could rely on 5 vessels that could be used for landing operations, these were classified as “tankers” (Cisterne) and were the Adige and the 4 units of the Sesia class. They were characterized by a ramp at the end of the bow, a common trait of the late war landing crafts. These units could carry around 500 men each and a few vehicles and light artillery pieces. A simple calculus can suggest that, although fitting the role, they were not available in sufficient numbers for the supposed invasion of Malta.

Figure 6 The Scrivia (Sesia class) on the day of her launch

Figure 7 The Adige entering the “Mar Piccolo” in the base of Taranto

As was the case in all other nations, except for Japan, landing crafts were available (if existent) in few numbers, able to support small-scale operations of Marine infantry. In the Italian case, these 5 ships were able to carry the entire force of the San Marco Marine regiment.

The two battalions of the San Marco available in the summer of 1940 were certainly not sufficient to take Malta, and thus more men from the Army were required for the task. The Italian navy planners were aware of this and the only solution was the seizure of caiques and Bragozzi, wooden boats used mainly for fishing and light transport. It goes without saying that such fragile boats would have incurred heavy damages (and thus human casualties) even against light and heavy machine guns.

Figure 8 A militarized “Bragozzo” in 1941

Having said that, no army units were trained enough or at all for amphibious operations so everything would have been developed from scratch. In addition, only a handful of airborne troops were available at that time; the Libyan paratroopers also known as “Fanti dell’Aria”.

Besides all these issues, one should also consider the balance of naval forces in the region by the time of the entry into the war of Italy. The Regia Marina could rely only on two Cavour class battleships at the time, as the two Littorios and the two Duilio were under completion. Together with the heavy cruisers available, they would have escorted the invasion fleet, proceeding at very slow speed, a maximum 8-9 knots in the best case. Once the invasion had commenced, they would have faced the inevitable intervention of the Mediterranean fleet and the Marine Nationale. The two allied navies had a force of 9 battleships deployed in the Mediterranean, which could have arrived near Malta within 30-36 hours.

This time frame was, beyond any reasonable doubt, insufficient for the invasion force (if it managed to land sufficient forces) to defeat Malta’s defenders. Thus, once the allied fleet had arrived, the Regia Marina would have fought a desperate fight against superior enemy forces or fled, abandoning the invasion force on the island without supplies.

The Italian declaration of war

It must be remembered that Mussolini decided to enter the European conflict with the belief that the war would have ended in the space of a few months. Everybody was well aware that the country and the armed forces were not ready for a prolonged war, but the fall of France and the reassurances of the Italian dictator to his military leaders about the limited duration of the war defeated any skepticism. Imagining a short war, with Malta just capable of defending but not attacking (as both the Royal Air Force and Navy had abandoned the Island), any idea for an invasion of Malta made little sense, especially given the risks inherent to the operation. In September it became clear that the War would have continued for a little longer but the season was now unfavorable for any invasion attempt (with all the other problems still standing). By the summer of 1941, the situation had drastically changed and the events took another course.

Sources

Mariano Gabriele (1990), Operazione C3, USMM

Philip Vella, Malta blitzed but not beaten

Tullio Marcon, La mancata invasione di Malta: https://caiscuola.cai.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/marcon.pdf

Douglas Austin (2001), The place of Malta in British Strategic policy 1925-1943: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1317691/1/271101.pdf

Gianluca Bertozzi, Il piano di invasione di Malta del 1940: https://www.ocean4future.org/savetheocean/archives/48699

The Malta Garrison: https://www.maltaramc.com/regsurg/rs1940_1949/rmo1940.html