Secrecy and preparations

The negotiations between the Italian government and Eisenower’s envoys during the summer of 1943 were immersed in deep secrecy. In Italy, just a few members of the Government and of the Army knew about the negotiations and their actual status.

Raffaele De Courten and Renato Sandalli, the Navy and Air Force Ministers (who were also Chiefs of Staff in their armed forces) were too left in the dark.

On the 3rd of September, they were informed by General Ambrosio, chief of general staff, that “negotiations” with the allies were ongoing. The truth was that on that same day, the armistice was signed in the Sicilian town of Cassibile, by Eisenhowers’ delegate, General Bedell Smith and by the Italian envoy, General Giuseppe Castellano.

In the following days, De Courten and Sandalli received scattered updates from Ambrosio, confirming the progress in the negotiations and prospecting the announcement of the armistice sometime between the 10th and the 15th of September.

Perceiving the gravity of the moment, Admiral De Courten summoned a meeting in Rome with the high-ranking Admirals in charge of naval forces and bases. The meeting took place on the morning of the 7th of September.

Prior to the meeting, De Courten had a private talk with Admiral Carlo Bergamini, the commander of the battle fleet, stationed in La Spezia. During those early days of September, the fleet was on high alert and ready to face the forthcoming allied landings in mainland Italy. The fleet was ready to commit in this final and suicidal act, however, things would have evolved differently.

The main subject of the Admiral’s meeting was a document called Promemoria n.1 which listed a series of actions to implement in the case of a German aggression, having the objective of removing the current government and reinstalling Mussolini or some forms of fascist rule.

These actions were aimed at securing the naval units, preventing the Germans from capturing them, sabotaging all the merchant or military units that could not leave port and destroying or capturing any unit of the Kriegsmarine. The document did not mention the armistice, but two specific points gave some indisputable clues. One talked about the need to prevent the Germans from sizing allied POWs and the second prescribed to open fire against German aircraft and not against allied ones.

The participants understood the situation, took their notes and returned to their command posts.

The Armistice comes

On the troubled afternoon of the 8th of September, Badoglio told De Courten and the other unaware members of the government that the armistice had been signed and the allies were about to announce it. In fact, during the meeting, news came that General Eisenhower was announcing the signing of the armistice on Radio Algiers.

This caused some negative reactions and harsh discussions during the meeting but ultimately the King put an end to the discussion saying that Italy would have kept the word. While Marshal Badoglio went to the EIAR broadcast centre to publicly announce the armistice to the population, Admiral De Courten raced to the Ministry and met with Admiral Sansonetti (Navy deputy chief of staff).

They started to issue orders and clear directives to all the subordinate commands and naval forces, and thanks to their decisive action the Regia Marina did not fall into disorder or cease to exist as a cohesive fighting force, as was the case for the Army, whose command was guilty of abandoning its soldiers without precise orders.

Admiral De Courten

Admiral Sansonetti

During the early hours of the 9th of September, De Courten was ordered to leave Rome with the King and the resto of the Government. He instructed Sansonetti to assume command and to keep issuing orders and communication to all naval units and bases.

The fate of the fleet

It was vital to secure the main body of the fleet, anchored in La Spezia, and Courten had two phone calls with Admiral Bergamini. The news of the armistice was not met with enthusiasm and the prevailing opinion among the officers was that of scuttling the ship.

De Courten spoke about the need to preserve the fleet since the loyal respect of the armistice terms and all subsequent efforts against the Germans, would have eased Italy’s position at the end of the war (this was basically the content of the Quebec declaration, subscribed by Roosevelt and Churchill back in August). In the last phone call, Bergamini assured De Courten that the fleet would have sailed immediately, making route for the Sardinian Island of La Maddalena.

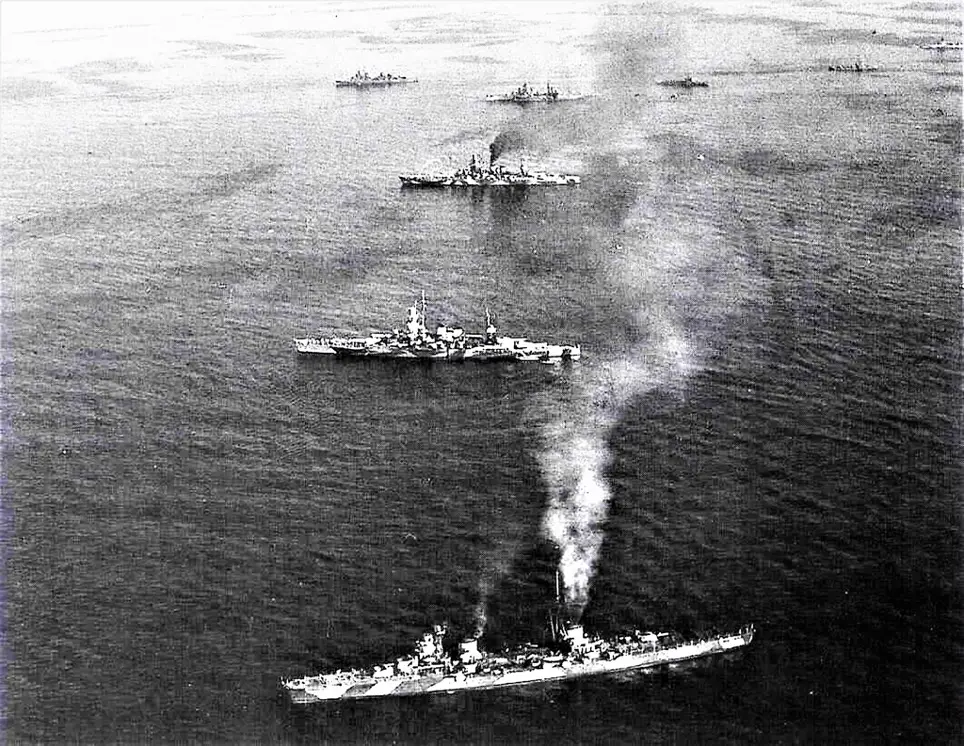

This powerful formation, with 3 battleships, 6 cruisers, 8 destroyers and 4 torpedo boats came under the attack of Luftwaffe bombers, armed with PC 1400 X and Hs 293 glide bombs. The German aircraft attacked the Italian formation near the island of L’Asinara and two bombs hit the flagship, Roma. The second bomb proved fatal since it penetrated the ammunition magazines, causing the ignition of the propellant charges that erupted in a column of fire and smoke.

Admiral Bergamini died on the spot and the ship sunk after 20 minutes. A section of the fleet was detached to rescue the survivors from Roma. Admiral Romeo Oliva, on the cruiser Eugenio di Savoia, assumed command of the formation, which arrived in Malta on the 11th of September.

The sinking Roma

In the same hours, the destroyers Vivaldi and Da Noli had crossed the strait between Sardinia and Corsica, in the attempt of rejoining with the bulk of the fleet. They harassed a group of German transport crafts, but in doing so, the two destroyers came in a range of coastal batteries and while attempting to evade, Da Noli struck a mine and rapidly sank. The Vivaldi managed to escape but was later attacked and heavily damaged by Luftwaffe bombers using the glide bombs Hs 239. The crew later scuttled the ship when they ran out of water for the engines.

The Taranto division

At Taranto, Admiral Alberto Da Zara was in command of the two battleships Duilio and Doria, the cruiser Pompeo Magno and Cadorna and one destroyer. After receiving news of the armistice, Da Zara gathered his commanders and discussed the situation.

The overall sentiment was that of obeying orders and thus the small fleet under Da Zara departed for Malta in the afternoon of the 9th of September, passing along the incoming British ships destined to land an airborne division in the Gulf of Taranto (Operation Slapstick). Da Zara’s ships arrived in Malta on the XX of September and where the Ships coming from La Spezia arrived, he assumed overall command of the Italian battle fleet and met Admiral Andrew Cunningham.

Italian ships at anchor in Malta

The voyage of the Cesare

The armistice announcement reached also the crew of the old battleship Giulio Cesare, stationed in Pula, where she was stationed as a training ship. Commander Carminati and the crew gathered all the fuel and other supplies they could and left the port in the afternoon of the 9th of September, escorted by the torpedo boat Sagittario and the corvette Urania.

During the crossing of the Adriatic Sea, a group of officers, unaware of the Navy instructions, locked the Commander in his room, fearing that the ship was to be handed over to the Allies, preferring to scuttle her instead. The Captain then explained that the ship was not going to be surrendered, remaining instead in Italian hands. The situation was re-established and Carminati re-assumed control.

Along the way, the Cesare was joined by the seaplane carrier Giuseppe Miraglia and the two ships reached together Taranto, where they re-fuelled and then proceeded to Malta, arriving on the 13th of September.

The beginning of the co-belligerence

With Cesare arriving in Malta, the bulk of the Italian fleet in the Mediterranean had been finally gathered and the Regia Marina had loyally respected the armistice terms. Da Zara first, and De Courten later will meet Admiral Cunningham agreeing on the role that Italian units would have assumed in the struggle against Germany.

This would have been important for building the basis of the Italian co-belligerence. It is important to stress that not a single ship lowered the Italian flag, nor they were handed over. On the contrary they would soon become part of the allied cause, playing their part in the liberation of Italy from the Nazi occupiers.

Sources

Fioravanzo, G. (1971). La Marina dall’8 settembre 1943 alla fine del conflitto. USMM.

O’Hara, V. P. (2008). Struggle for the Middle Sea: The Great Navies at War in the Mediterranean Theater, 1940-1945.

Pasqualini, M. G. (2023). 8 Settembre 1943-25 aprile 1945 – La Resistenza dei Militari Italiani: un lungo percorso sino alla vittoria finale.

USMM, a cura di M. Gabriele (1993), Le memorie dell’Ammiraglio De Courten, 1943-1946