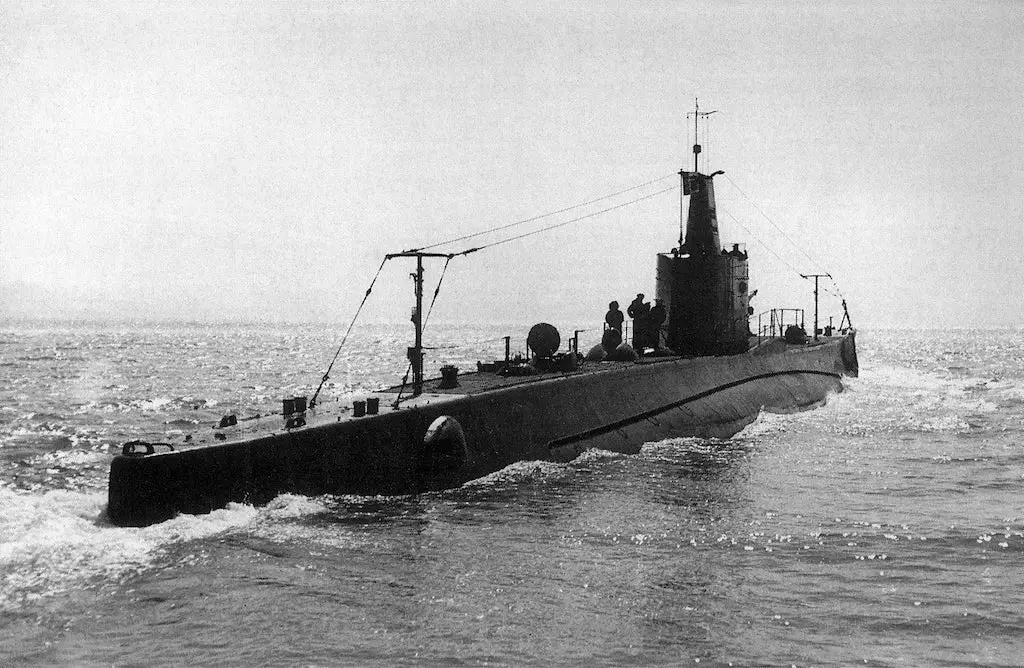

The Marconi Class submarine Leonardo da Vinci conducted 11 war patrols and sank 17 ships totaling 120,243 GRT. It was the most successful non-German Axis submarine in World War Two. Commanded by Italy’s most effective submarine ace, Gianfranco Gazzana Priaroggia, it sank in an intense depth charge attack on 24 May 1943.

Italian submarine Leonardo da Vinci.

Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic was the most prolonged continuous running battle of the Second World War. Between 1939 and 1945, the Axis powers dispatched hundreds of submarines into the Atlantic in an attempt to strangle the flow of supplies and materials being sent to countries opposing the massive Axis onslaught that initiated the war. The primary recipient of these desperately needed supplies was Britain. At first, as a means to keep them in the war, latter to build up military strength for a cross channel invasion. If the Axis blockade was successful and England forced to capitulate, it would significantly hamper, if not outright eliminate the chances for an ultimate Allied victory.

The Kriegsmarine was by far the dominant participant in this critical fight for the Axis. They would send into battle some of the most advanced submarines of the time, guided by many of the greatest commanders in the history of underwater warfare. While the Mediterranean was the central area of battle for the Regia Marina, their submarines also patrolled the Atlantic to assist in the Axis cause.

During the three years of Italian participation in this epic struggle, Italy’s submarine crews fought with heart and courage during their war patrols on and below the waves of this immense battlefield. At the forefront of the Regia Marina’s submarine effort was the Leonardo da Vinci, the most lethal Italian hunter of Allied shipping throughout the entire Second World War.

Leonardo Da Vinci Submarine Specifications

This Marconi-class submarine first launched on 16 September 1939. She was 76.5m long and displaced 1465 tons fully loaded. She could reach a top speed of 17.8 knots on the surface, and 8.2 knots while submerged. The submarine armament consisted of (1) x 100 mm deck gun, (4) x 13.2 mm anti-aircraft guns, and (8) x 21″ torpedo tubes.

On 22 September 1940, she departed Naples for Bordeaux in occupied France, home of Italy’s main Atlantic submarine base known as BETASOM. In command was Ferdinando Calda. Navigating safely across her “home waters” of the Mediterranean, the da Vinci passed undetected by the British at the critical juncture at the Straight of Gibraltar on the 27th. She immediately began operations in the vast expanse of the Atlantic Ocean.

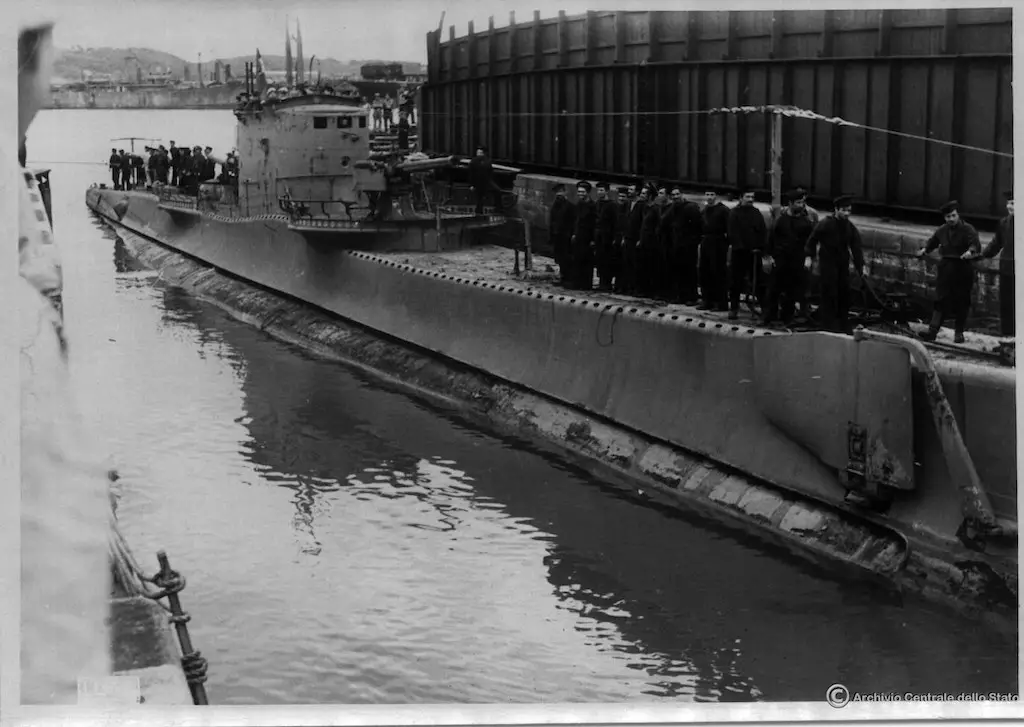

Submarine Barbarigo at the BETASOM Italian submarine base in Bordeaux, France. June 1942. Archivio Centrale dello Stato.

Harassed by two British destroyers during an early engagement she undertook on 30 September. A quick crash-dive led to her escape from potential destruction. The Leonardo da Vinci reached the safety of Bordeaux on 31 October 1940. During her maiden patrol, she had come up empty on a few attempted intercepts with Allied vessels. However, significant success lay ahead.

As stated, success would come for the da Vinci and her crew, but it would not come quickly. Her first two patrols of the Atlantic proved unsuccessful. One patrol lasted December through January, and the other spanned March through April of 1941. Both patrols conducted in the waters off of the coast of Ireland. She returned to Bordeaux from each voyage without a kill, but her crew gained some valuable lessons and experience.

Italian vs. German Submarines

The technical and performance limitations of Italian submarines operating in the northern Atlantic waters were becoming quite apparent by the spring of 1941. Italian subs were, for the most part, more massive than their German counterparts, making them easier to detect and or fall under attack by the Allies.

Italian submarine warfare doctrine generally called for their subs to operate beneath the surface while engaging a vessel. The initial torpedo attack would come while submerged. Then the sub could rise to the surface to finish off the target if applicable. Longer periscopes were essential to fit this type of submerged warfare. Thus a more massive conning tower was required on Italian submarines in comparison to the German U-Boats.

In contrast, German submarines would mostly engage their targets on the surface. Hence their subs were designed to give as little of a silhouette as possible. Italian subs also took longer to complete an emergency dive, which is a critical feature in avoiding a surface attack or engagement. Regia Marina submarines were not necessarily designed to make a quick retreat after the initial engagement. The failure in seeing the importance of an emergency dive feature led to less emphasis or focus on that capability. However, it was a crucial feature in the construction of German subs. An additional shortcoming for the Regia Marina was the fact that their submarines could not match German U-Boat speeds, either submerged or while on the surface.

German Wolf Pack and Italian Lone Predators

The preferred method of attack for the Germans was to deploy their subs into “Wolf Packs.” A Wolf Pack includes several submarines working in unison to track and attack a ship or convoy. Italian Navy submarines had difficulty working with the Germans in this type of joint operation. The challenge was mainly due to communication and coordination problems with their German counterparts. Kriegsmarine leadership also felt Italian submarine officers did not possess the same qualifications compared to their own. The colder waters of the North Atlantic also began to take its toll on an Italian submarine fleet designed to operate mainly in the warmer Mediterranean waters.

Thus, starting in the spring of 1941, taking all of these factors into account, Italian submarines would be mainly deployed in the central and southern waters of the Atlantic. Regia Marina doctrine generally called for their subs to operate independently, instead of using German “Wolf Pack” tactics. The German tactics proved inefficient for the Italians. So as she prepared for her next patrol, she would do so not as a member of a pack, but as a lone predator stalking her prey.

First Kill and New Commander

The Leonardo da Vinci set sail for the waters west of Gibraltar on 18 June 1941. Ten days later, she made her first strike against the enemy. After slamming several torpedoes into the hull of the oil tanker Auris, the da Vinci and her crew found their first success of the war by sending the British vessel to the ocean’s bottom. The da Vinci would come up empty-handed on the rest of the patrol, but the monkey was off her back. She spent the next several months at BETASOM, undergoing several overhauls and refits to improve her overall performance and range. C.C. Luigi Longanesi Cattani replaced Ferdinando Caldo as commander of the da Vinci in the fall of 1941. It would be under his command when the da Vinci set sail for the trade routes off the coast of Brazil.

Mid Atlantic Trade Route

The Allies utilized a trade route stretching from New York to Brazil for the previous two years. For the most part, they were left unmolested by Axis interference. The Regia Marina deployed the Leonardo da Vinci and several of her sister ships to target this Allied trade route.

Most of the initial Axis submarines sent to the Brazil-Antilles area to harass the Allied Merchant Fleet were Italian. The Germans were still ramping up the production of their newer, longer-ranged submarines. The Italian subs, due in part to their larger size and excellent range, were more suited for these lengthy patrols. It took the da Vinci about a month to make that first voyage to the waters off South America. So for now, Italy would take the lead for the Axis in this sector of the war.

On 25 February of 1942, the crew obtained their next successful attack. Sighting the Brazilian flagged SS Cadebelo, the da Vinci stalked then sank the vessel in a devastating torpedo attack. Just two days later, the SS Everasma, hailing from Latvia, became its next victim. About two weeks later, da Vinci began her voyage back to Bordeaux. The long, cramped journey back for the crew made more enjoyable by the success they had obtained.

African West Coast

Out on the hunt once again in May 1942, this time patrolling off the west coast of Africa near Liberia, the submarine picked up right where she had left off. The Reine Marie Stewart, a Panamanian schooner, had the misfortune of coming into her sights on 2 June 1942. The da Vinci made quick work of her and moved back out on the prowl. During this patrol, she sank three more Allied Merchant vessels: the Danish vessel Chile, followed by the Dutch Alioth, and finally, the SS Clan MacQuarrie from England. After completing this mission, she headed back to Bordeaux for rest and a refit.

Planned Attack on New York City

The da Vinci would play a role in an ambitious Italian plan to bring the war to America. A strike on New York City. During the summer of 1942, the da Vinci underwent structural modifications in Bordeaux to carry and transport a CA class Midget or “pocket” submarine for use in a planned clandestine attack against New York City.

This proposed operation was being headed up by Junio Valerio Borghese, Decima MAS’s top tactician, and commander. The plan called for the da Vinci to transport the CA sub and Decima Mas commandos across the Atlantic to the mouth of the Hudson River. From there, the CA sub would stealthily move up the Hudson to target the ships moored in New York City’s harbor.

Borghese in the early 1940s.

While part of the mission objective was to inflict material damage through a sub attack and or actions by the Frogmen, its primary goal was to land a psychological blow to the American people.

Related: Decima MAS: Italian Frogmen

Borghese later spoke of the envisioned plan:

“An attack on New York, taking the ‘CA’ up the Hudson into the very heart of the city. The psychological effect on the Americans, who had not yet experienced war on their soil, would, in our opinion, far outweigh the material damage which it might inflict”.

Trials with the CA Mini sub looked promising, and the excitement within the Regia Marina was palpable. Further modifications to the CA sub were needed. The mission was delayed to allow for this. However, with Italy’s volatile position in 1943, the mission to attack America would never take place. Back in the fall of 1942, however, the da Vinci would head back out to do what she did best, stalk Allied shipping.

New Commander: Gianfranco Gazzana Priaroggia

The da Vinci embarked from Bordeaux in October with a new man in command. Cattani had moved on and replaced by Gianfranco Gazzana Priaroggia, one of the greatest submarine commanders of the Second World War. She was Priaroggia’s fifth submarine command. He ultimately oversaw the sinking of over 90,000 Gross Registered Tonnage of Allied shipping. Priaroggia was Italy’s top submarine ace. One of the highest non-German scoring submarine commanders of WW2.

Gianfranco Gazzano Priaroggia

On 2 November, the da Vinci intercepted and sank the British SS Empire Zeal, with a well-placed torpedo salvo. Three days later, she located and sank the Greek SS Andreas. The da Vinci and her crew were operating with peak efficiency.

Five days after sinking the SS Andreas, she came across the American Liberty Ship SS Marcus Whitman. The submarine slammed several torpedoes into her hull, sending it to the bottom of the Atlantic. The next day, using her deck cannon, the da Vinci riddled the Dutch vessel SS Veerhaven with devastating fire. The Veerhaven slipped silently beneath the water and became the fourth and final victim on this very successful patrol.

South Atlantic

The spring of 1943 found the da Vinci and her crew in the extreme southern Atlantic waters off Africa. They even ventured into the Indian Ocean. The journey to her patrol area was long and tedious. Still, she made it worthwhile. On 14 March 1943, the da Vinci sank the largest vessel of her career, the massive 21,517 ton troop transport Empress of Canada. The Empress’s primary role had been to transport troops from Australia and New Zealand to the Mediterranean and European war zones from their home countries.

In port during 1941.

On the day of her demise, she carried Polish and Greek refugees, along with over 500 Italian POWS. It was a perfectly executed attack that unfortunately took many civilian lives. The da Vinci’s crew knowledge that they inadvertently killed several of their own countrymen offset any fulfillment felt from the kill.

The sailors of the da Vinci carried on, however, and just four days later engaged and sank its next victim, the Lulworth Hill. By mid-April, she operated off the coast of South Africa, officially in the Indian Ocean. On consecutive days starting on the 17th, her torpedoes struck fatal blows to both the Dutch SS Sembilan and the British Manaar. Another successful engagement occurred on the 21st. The da Vinci intercepted and destroyed the 7,177 ton American Liberty ship, John Drayton.

The rich shipping waters provided one last victim in April. As fate would dictate, it would be the last ever for the da Vinci. The British oil tanker Doryessa, en route to the Persian Gulf, floundered and sank minutes after da Vinci’s torpedoes found their mark against her hull.

Leonardo Da Vinci Sinks

Almost a month after this last attack, she radioed home to BETASOM. She was heading back to the port. The journey should take approximately a week. The next day, 24 May 1943, the da Vinci came across Allied convoy WS-30 – KMF-15. Although well guarded, the da Vinci attempted one more strike before continuing home. However, time and luck ran out for the da Vinci. As so often happened in this epic Battle of the Atlantic, the hunter became the hunted.

Working in tandem, the British frigate HMS Ness and destroyer HMS Active, detected, trapped, and then sank the Leonardo da Vinci with an intense depth charge attack. The tables turned on the da Vinci and her crew. The fearsome standard-bearer of the Italian Atlantic submarine force sank into the same crushing depths that she had sent so many others.

The submarine and her crew showed their worth to the Axis cause during her time in the Atlantic. She sank 17 Allied merchant vessels from over a half a dozen different countries during her participation in the war. The da Vinci’s patrolled an immense area. It patrolled the coast of Ireland, the South American routes to the tip of Africa. She performed admirably in her role, and will always be remembered as one of the brightest stars of the Regia Marina.

References:

RegiaMarina.net

www.britannica.com

naval-history.net