Late February 1941, Italian and British armed forces fought a relatively minor, yet strategically important, battle over the small island of Castellorizo. The clash was short, yet its outcome helped define the course of the war for both of its combatants in this region of the world. It would be known as Operation Abstention, the Battle for Castellorizo fought between 25-28 February 1941.

The Island of Castellorizo

The island of Castellorizo (Kastellorizo) lies within the Aegean Sea, approximately a mile off the Turkish shore, and for decades was one of the many Isles comprising the Italian Dodecanese (Isole Italiane dell’ Egeo). The Italian fleet first occupied the archipelago in 1912, and Italy acquired Castellorizo from France in 1921 via the Treaty of Lausanne. This helped strengthen the far eastern defensive perimeter of Benito Mussolini’s ‘New Roman Empire ’at the onset of the Second World War.

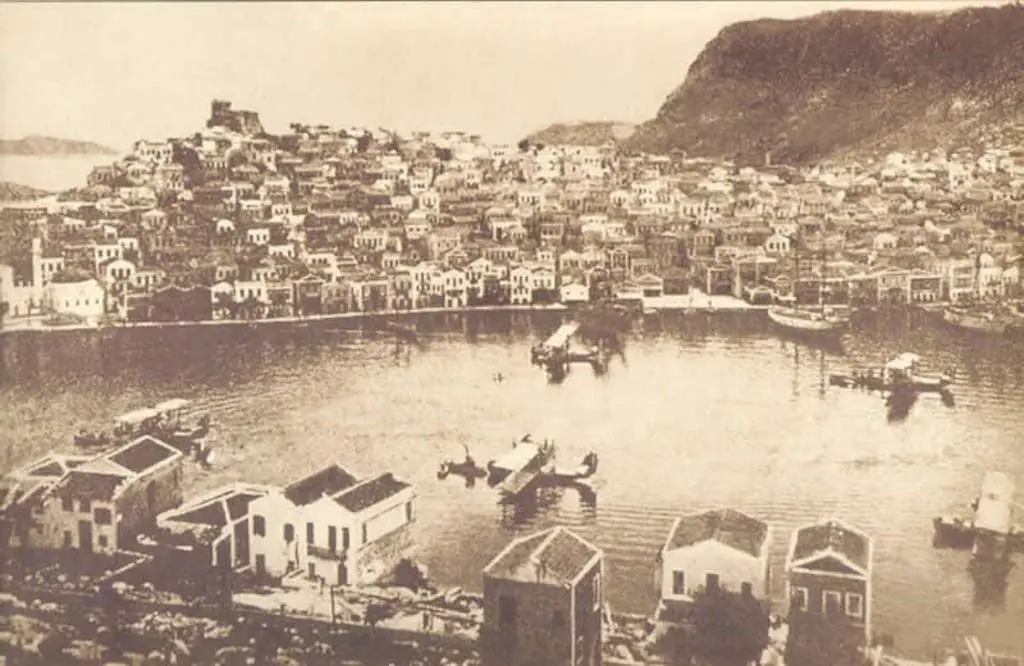

Castellorizo’s Harbor.

Castellorizo is small in size, with a total area of about 5 square miles. The local population stood at approximately 1,400 in 1940. During the Italian occupation, taxation without representation and restrictions levied against the Greek Orthodox Church made life tough on the local population. It fostered strong anti-Italian attitudes among some. On the other hand, the Italian’s public works programs throughout the Dodecanese greatly improved the infrastructure of the islands, creating facilities to meet many essential needs including medical buildings, schools, and communication networks. Trade between the Italian Dodecanese and Italy, and among the islands themselves, continued to grow throughout the years, as did Italys military strength in the region.

A Strategic Importance

The necessity in commanding the Dodecanese islands to control the Aegean during a time of war had been appreciated by engaged military leaders for centuries; from antiquity to the dawn of the Second World War. At the turn of the twentieth century, possession afforded the Italians advantages during several conflicts; the multiple ports provided the Italian fleet anchorage for the blockade of Crete in 1897 and served as a forward base against the Turks during the Turco-Italian War (1911-12).

During the Second World War, maintaining command of the Aegean Sea once again took on prominent importance. The Dodecanese Islands, principally the island of Rhodes, would furnish the Axis Powers with a distant outpost granting them the ability to employ a defensive screen to help check Allied activity in the Eastern Mediterranean. By preserving dominion in the Aegean, along with the Adriatic and Tyrrhenian Seas, which together stretch like fingers emanating from the Mediterranean up to mainland Europe, the Italians and Germans would be able to stonewall Allied attempts to utilize these ‘sea lanes’ to unbalance the Axis’s role as ‘masters’ of the continent.

Map of the Aegean region under Axis control in 1941.

For these very same reasons the Allies, in particular, United Kingdom, coveted these vital landmasses in the southern Aegean. Furthermore, a belief held by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was that Allied possession of the Dodecanese could possibly usher in far greater benefits than just anchorage and aerodromes; acquisition had the potential to deliver a powerful political and symbolic statement to neutral Turkey, which Churchill hoped would act as a first step in the country’s induction into the Allied fold.

United Kingdom Desires Turkey to Join the Allies

Churchill’s ambitious idea of opening a ‘new front’ in the war through a ‘Balkan alliance’ featuring Turkey was dependent upon persuading the neutral government to join the Allies. Churchill envisioned that the dozens of new divisions that would be drawn from the armed forces of the Balkan ‘allies’ could be directed at the German and Italians, forcing the Axis to expended a great deal of manpower and supplies to counter this new threat on their flank. Additionally, airfields in Turkey could be used by the RAF to threaten the critical Nazi oil supply originating from the rich Romanian oilfields.

However, by early 1941, Turkish President Ismet Inönü remained hesitant to embrace British overtures to join their cause. The outcome of the war was far from decided, and in fact, for many observers, it appeared to be going the way of the Axis. The British concluded that bold action would be required to sway the reluctant Inönü, and as far as Turkish concerns were focused, the seizure of the Italian Dodecanese and ultimate control of the Aegean Sea could be the move to accomplish this goal.

Goal of Operation Abstention

While Churchill dreamt of the possible political ramifications that could be wrought by securing the Aegean, his military commanders were focused on the potential strategic gains to be had in regards to the conduct of the war. A first step in executing their plan was to gain a foothold in the Dodecanese that could support further, and presumably grander, endeavors. Operation Abstention would be the spark that would begin the process, and the island of Castellorizo the target. This small island would serve as the front-line in which each side’s regional aspirations would be determined.

Operation Abstention was slated for late February of ‘41 and would draw upon British and Commonwealth naval units emanating from Cyprus, Alexandria, and Crete. The total force employed was quite impressive and helps illustrate the importance that British leadership placed in the mission. Firepower and support could be called upon from two cruisers, seven destroyers, one submarine, one gunboat, and for good measure, one armed yacht.

Initial Force

The responsibility of establishing a beachhead on the island would fall on the shoulders of 200 special commandos, who were to be transported on the destroyers HMS Decoy and HMS Hereward, along with a group of 24 marines, shuttled aboard a naval gunboat, the HMS Ladybird. These men would be asked to overwhelm and subdue the Italian garrison, establish a defensive perimeter, and prepare for the arrival of the second force slated for the next day.

Governor of the Italian Aegean -General Cesare De Vecchi (center) on an inspection tour in the Dodecanese. Admiral Biancheri stands to left in the picture.

Augmenting Force

That second force sailing from Cyprus consisted of the light cruisers HMAS Perth and HMS Bonaventure, destroyer escorts, and the armored yacht/boarding vessel HMS Rosaura. Carried among them was a company of Sherwood Foresters. They would be tasked with securing and defending the island en masse, ensuring that the newly won Castellorizo remained in possession of the British Empire. Shortly thereafter the Royal Navy planned on establishing a motor torpedo base in the island’s harbor, which located less than 80 miles from Rhodes, would give the British a vital forward operating base in their quest to supplant the Italians as overlords of the Dodecanese.

Operation Begins

Charged with overseeing Operation Abstention was Admiral Andrew Cunningham, one of the greatest naval officers of the war. He set his ‘fleet’ carrying the first wave of attackers to sail on February 24th, and a few hours after embankment, the war vessels had moved stealthily into position off the shore of Castellorizo. Shortly before the first light of February 25th, the order to begin operations was given, and the first echelon of landing forces aboard the destroyers set off for the island’s port, thus commencing the British’s first substantial attempt at claiming the Aegean.

Google map view of Castellorizo.

The British destroyers HMS Decoy and HMS Hereward proceeded unmolested into Megisti harbor; their unexpected arrival no doubt shocking the 35 man Italian Garrison. The Italian force on Castellorizo was small in stature and was comprised by a hodge-podge mix of soldiers and a handful of men of the Guardia di Finanza (basically heavily armed custom agents). Duties for the garrison entailed basic security and the overseeing of a communications station. The Italian’s defensive plan for Castellorizo counted on protection from forces stationed on nearby Rhodes; which was the primary base of Italian power in the Dodecanese.

British Commandos Deployed

The jolt of seeing the two huge enemy destroyers maneuvering into port quickly wore off, and a desperate firefight unfolded between the Italian troops taking up positions leading up to and around the harbor and the British commandos scrambling to disembark from the destroyers and move inland.

The British commandos carried the day, and over a third of the Italian force became casualties during this pointed encounter. The British commandos were able to secure the port and take multiple prisoners, but their mission was not a complete success. Before the radio station fell, the wireless operator was able to get off a warning to Rhodes with news about what had befallen the base; Italian reinforcements would be arriving.

Italian SM.79s

Regia Aeronautica Responds

The Regia Aeronautica was the first to respond. A contingent of Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 Sparviero and Savoia-Marchetti SM.81 Pipistrello was sent into battle from airbases on Rhodes by Rear Admiral Luigi Biancheri and attacked the newly won British positions just hours after the commandos had come ashore. Air bombardments against the gubernatorial castle, the harbor, and its surrounding facilities, along with the hillside which the British had concentrated their forces were carried out with positive results. The bombing also inflicted damage to the gunboat HMS Ladybird, which had replaced the destroyers inside the harbor to act as a communications hub for the ground contingent, forcing her to withdraw back to safety in Cyprus.

Italy Deploys Raider/Recon Party

Throughout the battle the Italian’s continued to rapidly press their counter-attack; their speed in reacting, starting from the very first bomber attack on February 25th, seems to stand in contrast to some of the moves and pacing made by the British during the encounter. Late on the 25th, some sources indicate early 26th, the Italians landed a small ‘raider/recon’ party on Castellorizo. The force was made up of soldiers from the 50th Infantry Division Regina. Approximately 65 men of the 201st CN and the 13th/ IV / 9th spent several hours running reconnaissance to gauge the composition and deployment of British strength while also conducting several hit and run attacks. After approximately 5 hours the force re-embarked on to their waiting vessels and safely departed after the successful endeavor.

No British Reinforcements

The second wave of the British invasion force, anchored by the Sherwood Foresters sailing aboard the boarding vessel HMS Rosaura, was scheduled to arrive on Castellorizo during the early morning hours of the 26th. The soldiers were to be shuttled into Megisti Harbor, mirroring the arrival of the first wave of commandos, to bring needed manpower and supplies. This scheduled landing would not occur, however, and the British commandos were denied the reinforcements they desperately required to help hold the island.

The advancing British convoy had received reports from Castellorizo of Italian naval activity north of the harbor. The reports were about the Italian torpedo boats Lupo and Lince, which had first dropped off the recon party mentioned above, and then after moving into range, proceeded to shell British positions from offshore. On receiving this warning, British Rear Admiral Renouf, who was overseeing the operation first hand, canceled the scheduled landing. Possibly unsure of the actual size or composition of the Italian force, Admiral Renouf feared for the vulnerability of the ‘smallish’ Rosaura and the troops she carried.

He ordered the convoy to turn around and head to Alexandria in order to transfer the troops onto larger and more heavily armed destroyers for a second attempt the next day. Renouf simultaneously ordered the destroyer Hereward, which had initially sailed away from the island on first reports of enemy naval activity, ahead in an attempt to engage the reported Italian maritime activity. The Hereward was unable to locate her adversaries and circled back around out to sea empty-handed. The British had lost the initiative.

Italian MAS (Motoscafo Armato Silurante)

Regia Marina Reinforcements

The Italians, on the other hand, were racing forward on the morning of the 27th to begin in earnest the land-based portion of their counter-attack. A naval flotilla, led personally by Admiral Biancheri, consisting of the torpedo boats Lupo and Lince, motor launches MAS546 and MAS561, and later in the day bringing heavy firepower, the destroyers Crispi and Sella. The flotilla would, on what proved to be the critical day of the conflict, deliver to Castellorizo nearly 340 soldiers and sailors, most of them hailing from the IV Battalion, 9th Infantry Regiment of the 50th Infantry Division Regina.

The force included about two dozen men from an anti-tank platoon with two 47-mm guns, and a mortar platoon equipped with a pair of 81-mm mortars. The Italians moved inland quickly, gaining ground as they advanced, and pushed the British back, eventually forcing most of the defenders to dig into a small area of the island known as Nifti Point. The Italian ground forces were supported during their advance from the Lupo offshore, which used its 3.9 inch gun to pound enemy positions. A good portion of the Lupo’s fire was directed at Nifti Point and its battered occupants, leading to serious questions of the tenability of this last bastion of British defense.

Royal Navy Reinforcements Arrive

Later that night (2300) the British once again approached Castellorizo, the Sherwood Foresters having been transferred to the destroyers HMS Decoy and HMS Hero, with the flotilla now filled out with an impressive array of firepower. Joining the troop-carrying destroyers were two further destroyers, the Jaguar and Hasty, and the light cruisers Bonaventure and Perth.

British Evacuation of the Island

The Foresters were disembarked back onto Castellorizo after midnight from their destroyers while the reaming British vessels took up patrols off of Nifti Point. Their stay on the island would not be for long. The commanders for both the commandos and the Foresters appreciated the extreme precariousness of their situation and the realization of the high probability that without sufficient air support they would not be able to hold their tenuous position on Nifti Point. It was therefore decided a withdrawal from the island was necessary, and within three hours of landing, the troops were evacuated under the cover of darkness back to their waiting vessels. British soldiers would not again set foot on the island for over two more years.

Sea Battle Continues

Several of the British commandos, who had either been cut off during the fighting or left behind during the evacuation, were captured by the Italians. Additionally, over two dozen men of the local population were arrested and later convicted of ‘aiding the enemy’, and eventually sent to Brindisi, Italy to serve their sentence. The Italian re-conquest of Castellorizo thus became one of the rare occurrences during World War Two in which Axis forces were able to recapture and hold through force an Island they had previously lost to the Allies. While the fighting on Castellorizo was all but over, out at sea elements of two of the most powerful naval forces on the planet would attempt to strike a ‘parting’ blow during the waning hours of Operation Abstention.

The Italians had positioned their MAS launches inside Megisti to help guard the newly reclaimed harbor. They were determined to have some firepower waiting inside the port area just in case the British decided to force an entry and landing with their warships once again. The Italians did not have to wait long, as in the early morning darkness the British destroyer HMS Jaguar swung into the mouth of Megisti harbor with torpedoes armed and ready.

However, the Jaguar was not attempting to land more troops. Instead, it was attempting a ‘hit and run’ attack on the Italians before the final British withdrawal. Perhaps not wishing to get entwined in a shooting match in the confined area of the harbor, the Jaguar fired all four torpedoes from the mouth of the port and fled. All missed the nimble MAS boats and slammed harmlessly into the shore. But the action was not over for the Jaguar, nor for the Italian Regia Marina.

HMS Jaguar dropping depth charges.

Crispi vs Jaguar

The Italian destroyer Crispi was on a patrol south of the island after earlier firing at least 20 rounds from her guns into British held areas of Castellorizo. Peering through the gloomy darkness the ship’s lookout called out a sighting on two contacts, one identified as a ‘cruiser’. The crew of the Crispi took immediate action and fired off two quick torpedoes at the nearest target, both of which missed running under the vessel. The Crispi, believing she was outnumbered and outgunned against a cruiser, attempted to slip off into the darkness before her enemy could launch a retaliatory strike. The Italian ship was immediately illuminated by a searchlight aboard the Jaguar, the vessel she had just fired upon. Although it was the Jaguar who had ‘lit up’ the Italian warship with her light, it would be the Crispi who would fire her guns in anger first.

The Crispi recoiled in the water as her guns blasted away into the morning dimness at the British vessel. She missed. The HMS Jaguar responded in kind with her guns, and likewise missed her adversary. The dueling destroyers were in such close proximity that each vessel opened up with their mounted machine guns, raking each other in fire. The Italians blasted out the Jaguars searchlight, once again plummeting the adversaries into darkness. The Crispi, who had sighted two enemy vessels before the firing started, took this opportunity to slip away into the obscurity, and with this action, the end of the battle for Castellorizo was complete.

Operation Abstention Fails

The failure of Operation Abstention came as a complete surprise to the British. Churchill’s dreams of Allied unity and power in the Aegean were dashed before they even started. The shocked Prime Minister stated in disbelief “I am thoroughly mystified at this operation.” Even the genius of Admiral Cunningham had not counted upon the Italians dealing his forces a loss in this endeavor; “A rotten business” is how the Admiral would refer to it during a post-analysis of the operation. Writer Vincent O’Hare assigned the blame of Abstention’s failure on the British’s tendency to underestimate their Italian foe, and summarized “…It would not be the last time the British suffered embarrassment in an operation where success depended upon a lack of Italian initiative.”

With the re-capture of Castellorizo so ended any serious British attempt of seizing the Dodecanese until the fall of 1943. With the Italians signing of the Armistice with the Allies that September, both the Germans and British attempted to fill the vacuum of power left behind in the Dodecanese caused by the Italian capitulation. British forces landed on Castellorizo shortly after the signing and would stay in possession of the island for the remainder of the war. The German Luftwaffe (air force) would inflict severe bombing damage, particularly in ‘43 and ‘44, on the island’s infrastructure and inhabitants until the Nazi surrender in the spring of 1945. By that time Castellorizo’s native population numbered less then 500, the rest having been evacuated to Cyprus and then Gaza for safety.

Why the Battle of Castellorizo is Hardly Known

The events of the battle for Castellorizo during Operation Abstention remain practically unknown, even for many scholars of World War Two. Information and accounts of the operation are scarce and are often reduced to a footnote or blurb if in fact mentioned at all in Western coverage of the War. There are several reasons for this including; the relatively small size of the forces involved in the fighting, the initially limited nature of the operation, the peripheral positioning of the combat area, and western writers’ proclivity to focus subject matter almost exclusively on the Western Allies and or German forces.

Italian Garrison on Kastellorizo marches to cemetery during ceremony to honor those killed during Operation Abstention, Nov 1941 Image: Vecchi.Altervista.org

Perhaps an additional reason for Operation Abstention lack of notoriety is the fact that the Italians won a quick and clean victory at the very onset of the operation, in effect dashing the British’s plans to expand their Dodecanese campaign into something more illustrious. It was over before it began, and the entire endeavor was limited to this relatively small encounter when compared to some of the massive clashes during the war. Churchill’s far-reaching strategic vision for the region was dealt a further blow when the Americans joined as an active member of the Allies, as they showed practically no interest in his Aegean/Balkan agenda. Without American support, concern in this area of the war was moved to the ‘back burner’ of Allied attention.

If the British Won the Battle

A successful conclusion of Operation Abstention for the British might have changed things. There are innumerable instances displayed throughout the war that demonstrate the fact that gaining one foothold, for example claiming a bridgehead across a river or knocking out a strongpoint in a village which opens a crucially needed road, has to lead to the turning of the tide of battle. Resources are often rushed to that breakthrough point, and from there, advances or gains can be realized and capitalized upon for the victors.

It is, of course, speculative to imagine what could have occurred had the British acquired their Dodecanese base of operation on Castellorizo in 1941. What is not left to the imagination are the results of the outstanding job Admiral Luigi Biancheri achieved by orchestrating a quick and coordinated counter-attack utilizing the air, land, and sea forces he had at his disposal. The Italian airmen, soldier, and seaman fought rapidly and effectively. They procured a notable strategic victory, even if the memory of this triumph has been swallowed up by the pure enormity of the Second World War.

NOTE: Special thanks to Dennis Hussey for editing the article. I appreciate the time and work you put into reviewing. Thanks as well to Jeff Leser for his editing work and content suggestions. I could not have finished the article without the help of both of you.

References:

Struggle for the Middle Sea: Vincent O’Hare

The Naval War in the Mediterranean, 1940-1943: Jack Greene and Alessandro Massignani

Referenced site excerpts from “L’Operazione ‘Abstention’ in Egeo” Part I and II: Guido Ronconi

Crete, the Battle and the Resistance: Anthony Beevor

http://www.kastellorizo.com

Wikipedia and historical or military web sources.