No Phony War

When Italy declared war on Britain and France, the Allies had already been in it for nine months. The British Dominions had mobilized as could be expected and their reinforcements were already on their way to England and the potential battle zones in Africa, the Middle East, and Singapore. France had transferred troops from their North African colonies to the mainland. As such, the Allies had had time to prepare themselves for the upcoming struggle much more than Italy.

Personnel of all kinds had been called up, shifting of important resources had taken place and most of all, events of the period had steeled officers and soldiers in all branches and areas. The same could be said for the civilian side of the Allied nations. For Italy, the situation had been much the same as the summer of 1939 for France and the British. While war seemed looming matters weren’t really taken seriously until it actually broke out, the Allies had a gracing period of nine months – notwithstanding the Norwegian Campaign and the war at sea. Italy’s army, navy, and air forces were thrown right into it pressed on by Mussolini’s urge to conquer French territory and the British immediate minor air and land offensives in the desert and across the Red Sea. There was no “Phony War” in the Mediterranean.

In Italy, there had been vacillations and many grandiose speeches by Mussolini. The Italian people were obviously worried about Italy entering into a new war and the same could be said for the higher officers of its armed forces. Reading Count Ciano’s diaries, one cannot but wonder how a country with an officer corps of such standing and opinions could ever enter into a war of such proportions and constellations. Also, there was little love lost between the leaders of the two Axis partners, King Victor Emanuelle III himself was an example of this, but both parties hoped to benefit from the exertions of the other and swallowed their doubts only to venture into an unsure future.

Mussolini’s eyes were on the French colonies in North Africa and the vast Balkan, a part of the world that once was under the Roman Empire. Various treaties established between Britain and Turkey, Greece and Romania earlier was perceived by Mussolini as a British plan of hemming in Italy, to restrict its future plans for Italian Lebensraum in the Balkans. He was further aggravated by the British (half-hearted) negotiations with the Soviet Union at the same time, a treaty that never came off. Instead, the Germans were able to temporarily pacify the Soviets through the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. All this added to the hostility developed during the Ethiopian crisis.

First to Start: Regia Aeronautica and Regia Marina

With their natural flux for movement, it was the air and naval forces of both parties which first came into play when Italy delivered its declaration of war to France and Britain on 10 June. The immediate major targets Mussolini wanted his subordinate leaders to achieve were the occupation of as large a portion of Southern France as possible, with Tunis as a possible bonus, and the occupation of Egypt with the Suez Canal. The Balkans would come later.

It was not as if Italy’s declaration of war came as a surprise to neither Britain nor France. Britain, in particular, had made preparations if not to improve its Mediterranean defenses to any major degree so as to limit any immediate damage to its bases and installations. We have seen that they reinforced their Eastern Mediterranean fleet in Alexandria with naval vessels of all sorts streaming through the Suez Canal and Gibraltar Straits, among them ten submarines from the Far East.

The French would have to be relied upon to cover the Western part, which was only natural with the French supply lines running between mainland France and its North African colonies. Even so, some French naval units took up station in Alexandria. Part of the British naval force in Alexandria was soon sent back through the Canal to establish escort for convoys through the Red Sea, a necessary precaution considering the Italian naval force stationed in Massawa, Eritrea, which consisted of no less than 9 destroyers, 8 submarines, and some support vessels. Still, Malta had no real fighter defense and Gibraltar did not have a proper airfield.

Italian Submarine Actions

The first major Italian moves were made by their submarine force. At the outbreak of war no less than 49 units were deployed through the Mediterranean, an impressive operational number when compared with the German and British submarine fleets. Their missions were split into reconnaissance, offensive, and mining operations. Already on June 6th, the laying of defensive minefields had started along the coast and on the first night of the war. The Sicilian channel was mined by surface mine-layers covered by a cruiser detachment. It was expected that the mining of these important waters should be opposed by the French Navy but it was nowhere to be seen. Partly due to problems with the mine-laying apparatus the result of the first submarine mining operations was unimpressive but it was a flying start for the keen Italian submariners.

HMS Calypso was the first Royal Navy ship sunk in the Mediterranean during the first month of war with Italy.

Playfair, the official RN historian, criticizes the lack of results yielded by the large Italian submarine effort at the beginning of June but the Italian submarine Bagnolini corrected this when it torpedoed and sank the cruiser HMS Calypso south of Crete on 12 June the first British naval loss in the Mediterranean. HMS Calypso was part of Cunningham’s raider force and sailed in company with her sister ship HMS Caledon. These ships were companions stretching back to the First World War. Caledon and the destroyer HMS Dainty took off the survivors from the Calypso but 40 sailors lost their lives. As a foretaste of the upcoming blockade of Malta, on the same day, the submarine Nereide torpedoed and damaged the Norwegian tanker Orkanger (8000 brt.) on its way from Alexandria to Malta. It was finally sunk by the Naiade the day after.

Anti-Submarine Warfare

The anti-submarine warfare as a whole gave the opponents some surprises. With a score of 3-10 to the Allies during this first period of the war, four of the Italian losses were in the Red Sea, these were relatively equal considering the number of units at sea, with an advantage to the RM. The British, when learning of their first three submarine losses believed these to be caused by mines, actually, they were all sunk by Italian surface vessels as a result of conventional submarine search and destroy mission, a capacity the RN did not expect the RM to have.

In an attempt to torpedo the cruisers Fiume and Gorizia in the Taranto Bay, HMS Odin was sunk in a counterattack by the destroyers Strale and Baleno. On the same day, RM Finzi passed through the Gibraltar Strait as the first one into the Atlantic. It was followed later in the month by Calvi, Cappelini, Malaspino, and Veniero. Finzi returned safely on 6 July. At one time 27 Italian submarines operated in the Atlantic from their bases in Bordeaux and Italy and they executed almost 50 passages through the Straits without incidents.

The French submarine force was also supposed to be an important factor, on the eve of war. No less than 29 French boats departed their bases to take up positions in the Western Med. At the same time, 9 RN submarines departed Malta and Alexandria to ambush the Italian navy outside their main bases and along the shipping routes in the Aegean. The Allied operational pattern for the submarine forces was that the French covered the area west of Sicilia with the RN units on the Eastern side.

Royal Navy’s 2nd destroyer flotilla left Alexandria already early on 10 June to search the area outside Alexandria for eventual potential enemy submarines. In the evening, even before the declaration of war had taken effect, HMS Decoy depth-charged a suspected submarine target south of Crete. Since it was submerged it was seen as a legitimate target, very much in line with Royal Navy traditions.

Just past midnight, Admiral Cunningham left Alexandria with his battle fleet, the WW1-vintage battleships HMS Warspite, HMS Malaya and the carrier HMS Eagle with a cruiser (5) and destroyer (9) escort to look for enemy convoys between Italy and Libya and, if possible, to pick a fight with the Italian Navy. Two cruisers, part of Cunningham’s force, were sighted South of Crete and Supermarina directed the 3rd Cruiser division with two destroyer flotillas across the Malta route. The 1st and 8th Cruiser flotillas patrolled the approaches to the Ionian Sea, at the same time as a destroyer force patrolled between Sicily and Malta.

Actually there were no Italian merchant convoys at the time, and for some weeks to be, as southbound supplies for the army in Libya were initially transported with naval surface vessels and submarines. Cunningham veered south towards the Libyan coast where part of his force, the cruisers HMS Liverpool and Gloucester, bumped into the small Italian gunboat Giovanni Berta outside the port of Tobruk and sank it with gunfire.

Together with G. Berta were the gunboats Palmaiola, Grazioli, and Lante but these got away unscathed. The port was also bombarded. Some damage to the coastal defense vessel San Georgio was claimed by RAF Blenheims from the 202nd group cooperating with the surface fleet but this is not confirmed by the ship’s logbooks. San Georgio was positioned in Tobruk port as a compliment to the local anti-air defense. According to RN annals, an Italian cruiser was at one time sighted by Cunningham’s force but got away. This is not mentioned by the Italians. Cunningham was back in Alexandria on the 14th and as he had not been able to make contact with the Italian fleet he misjudged this for lack of initiative, or willingness to fight, on the side of his opponent. Actually, the Italian Navy had reacted with numerous forces but had not been able to find the British units any more than the other way around.

Fate of the British Navy in the Mediterranean

To preclude the history a little it may be of interest to take a quick look at the destiny of some of the British ships participating in this first large RN operation in the Mediterranean. Their fates are, believe it or not, typical for many of the RN combat vessels during the first three years in the Med. The loss rate for the large, modern Home Fleet destroyers later dispatched to the Med was even greater. One could, therefore, with good reason, question whether the British leadership, during the prevailing general conditions, made a mistake when they decided to hang on to the Mediterranean Theatre and spend so many resources there.

As goes for land warfare, too, to damage a naval object can be even more taxing for the enemy than simply destroying it. This goes to show by the often superhuman efforts spent to save a damaged vessel, sometimes only making matters worse as the rescuers are exposing themselves to the fury of the enemy, or costly repairs taking up space for new-builds.

HMS Warspite, Admiral Cunninghams’s flagship was bombed and damaged by German aircraft in the vicinity of Crete on 22 May 1941. Having returned to Alexandria for temporary repairs she was further damaged by Italian bombing on the following day and had to be taken to the US for final repairs. She was out of service till January 1942.

HMS Malaya, during a quick trip outside the Med, was torpedoed by U-106 in the Atlantic on March 20th, 1941 while performing convoy escort duties. It was out of service till October 1941.

HMS Eagle, Cunningham’s only carrier at the time, was first seriously damaged when supporting Fleet operations in the Aegean on 1 November 1940 by near misses from Italian bombers flying from the Dodecanese. As a consequence, she could not participate in the Taranto raid of the same month. She was sunk south of Mallorca on 11 August 1942 by U-73 when performing escort duties for Operation Pedestal.

Cruisers

- HMS Orion was bombed and damaged south of Crete on 29 May 1941 when evacuating British army personnel from Crete and was out of service till May 1942.

- HMS Neptune went down on 8 September 1942 after venturing into an Italian minefield outside Tobruk.

- HMAS Sydney returned to Australia beginning of 1941. While searching for the German merchant raider Kormoran she was sunk on 19 November 1941 by the same with no survivors. Kormoran also went down.

- HMS Caledon was probably saved by the fact that she was declared unsuited for service in the Mediterranean in August 1940 and transferred to the East Indies squadron.

- HMS Gloucester was sunk by German dive-bombers west of Crete on 22 May 1941.

- HMS Liverpool was hit by air-launched (Italian) torpedo on 14 October 1940 and was out of service till March 1942.

Destroyers

- HMS Dainty was hit and sunk by a 500 kg. bomb while in Tobruk on 24 February 1941.

- HMS Vampire transferred out of the Med in May 1941 after developing excessive wear and tear from operations during the Greek campaign. Vampire was sunk by Japanese aircraft on 9 April 1942 while escorting the aircraft carrier HMS Hermes near Ceylon.

- HMS Defender was sunk by bombs outside Sidi Barrani on 11 July 1941.

- HMAS Waterhen was damaged by enemy bombing on 29 June 1941 off Sollum. She sank the following day while under tow.

- HMS Wryneck was bombed and sunk on 27 April 1941 while evacuating British troops from Greece.

- HMS Diamond was bombed and sunk on 27 April 1941 while evacuating British troops from Greece.

- HMAS Voyager left the Med in August 1941 for a major overhaul at home base and was lost on 25 September 1942 during landing operations on Timor.

Anti-Ship Torpedos

In the summer of 1940, the Italian Air Force had still not developed its most deadly weapon, the anti-ship torpedo units. This was first taken in hand in August 1940 when an experimental unit was established to develop a torpedo-bomber force.

From the beginning, crews and planes from this training unit were rushed into various missions as the need developed. They were to rack up an impressive list of achievements as the war progressed but also extreme losses in aircraft and crews.

Even if only one warship, HMS Quentin, was down-right sunk, a significant number was damaged when most needed by the enemy. The Luftwaffe did not have any pure torpedo-bomber units at this time, either, even if their Küstenflieger (equivalent to Coastal Command or Regia Marina) units had been operational on torpedoes since the beginning of the war with their Heinkel He59 and He115 machines.

The first two RAF Beaufort squadrons were also not ready in England until later in the Fall, For a long time, the British would still have to rely on the Fairey Swordfish biplane in this respect. Italy standardized on the SM.79 and SM.84 bombers, both equipped to carry two torpedoes even if only one was usually carried. When the Luftwaffe started in earnest to establish similar units they went to Grosseto in Italy to make use of Italian expertise and the Italian Whitehead (Fiume) torpedoes in their training.

British Bombers in Southern France

The Italian declaration of war on France was very inconvenient as everything was in the balance after the German assault across the Somme. The river defenses had been breached, the Germans were approaching Paris. As such the French were quite keen not to stir up the situation with the Italians, but the British urged them on. Churchill was, as could be expected, particularly keen on having the French more involved to ease the burden of his own countrymen in the Med.

As part of a larger force that made a fuel-stop in the Channel Islands, a smaller British bomber force was sent to Southern France to refuel there and press on against targets in Northern Italy. The main force completed their raid with negligible results but the other, smaller unit, was refused by the local French leadership to take off again on their mission from the French base. This actually happened as Churchill was in France to try to bolster the French will to keep on fighting the Germans. The RAF bombers had eventually to return to England without accomplishing their mission. One cannot but wonder why British bomber resources were used in this manner when the French army needed all the air support they could get against the advancing German army in the North.

French Naval Bombardment of Genoa

The French Navy, however, performed a quick raid against Genoa only a few days before the French asked for an Armistice. A destroyer force advanced along the Ligurian coast on the night of 13 June, and the day after, four cruisers and nine destroyers leaped out of the main French naval port of Toulon and bombarded the Italian towns of Genoa and Savona. They were able to approach their targets undetected and did some damage to the industrial areas ashore.

In the vicinity were the Italian destroyer Calatafimi and a unit of MTB’s of the 13th MAS squadron. As these went to the attack and the batteries ashore came into play the French turned tail and returned to Toulon. They got away unscathed except for a 152 mm shell that landed on the destroyer Albatros, killing ten French sailors.

MTB’s from the Italian 13th squadron responded to the French attack on Genoa.

An interesting detail is that the Italian foreign minister Count Ciano was also out looking for this French flotilla the day after. Ciano was a bomber pilot and had left his office in Rome to join up with his unit in Pisa as soon as the war began. Nothing was detected, however, as the weather was bad with low rain-filled clouds. The French were probably back in Toulon at that time. He also writes about reconnaissance flights west of Sardinia to look for the French transports between France and North Africa. Mussolini, on his side, was in a hurry to achieve a footing on French soil to become a factor in the following peace negotiations. His western Army was now moving in large numbers up against the French border but it would take 10 days before they were anywhere near ready to start the hostilities against France in earnest.

Air War Over France

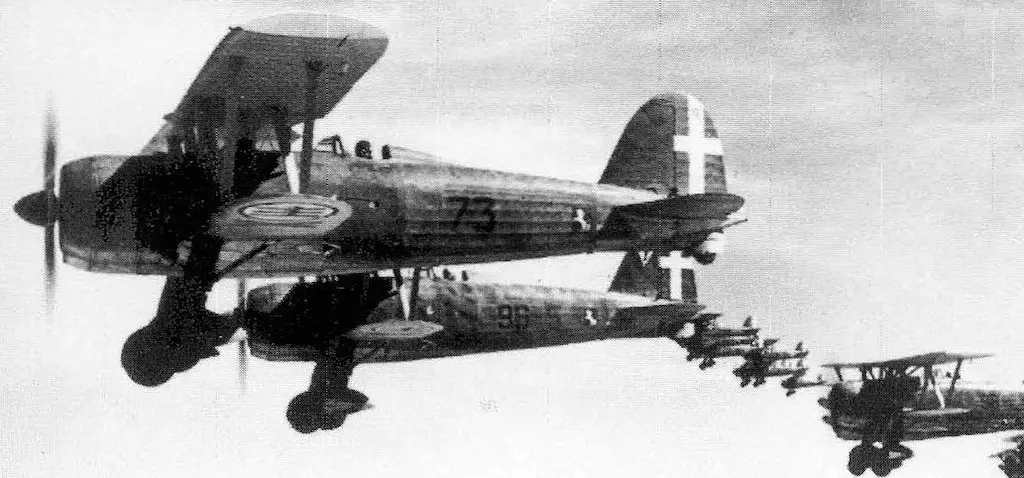

In the air, however, there was quite a lot of activity on the Western Front. Italian bombers, often escorted by the major Italian fighter type at the time, the Fiat CR.42 biplane, sprang forth from bases in Northern and Central Italy and Sardinia. There were fighter patrols over the Alps, attacks on naval and ground installations along the coast and much scouting over the shipping lanes between France and North Africa. I

f the opponents’ claims are to be believed it was a question of a rather equal give-and-take situation. The aerobatic-inclined Italian pilots in their very maneuverable but somewhat under-gunned biplanes against the well-trained French pilots in their solid, but sluggish cannon-armed MS 406 and Bloch MB152 fighters, interspersed with some of the new Dewoitine D.520 fighters, arguably one of the best fighter aircraft in the world at the time, whirled around, chasing each other under the Mediterranean summer sky.

Some of the Italian pilots had the misfortune to bump into Adjutant Pierre Le Gloan, whose unit had started converting to the D.520 at the end of May. Up till now, he had shared claims in 4 German bombers. Within two days, 13th-15th June, he would claim, and get credit for, 3 Fiat BR.20 and 4 CR.42’s. The third BR.20 was downed together with the 4 Fiats in one single sortie. Later Le Gloan claimed 5 RAF Hurricanes and one Gladiator in the fight for Syria in 1941. He was killed in an accident in North Africa in September 1943 flying a P-39 Airacobra for the Allies.

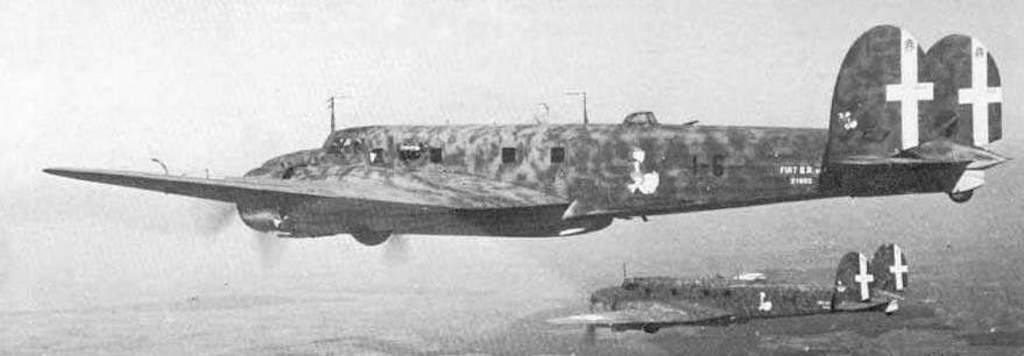

Compared with bombers of the other warring parties, the Fiat BR.20M was at its peak in the Summer of 1940.

The pilots of the excellent Italian bomber planes, the Fiat BR.20M’s and the SM79’s, soon found, like the pilots of the world’s other air forces, that day operations without fighter escort could be a dangerous business. The defensive armament of the single bombers would often not stand up to the concentrated fire of an elusive target like a fast-moving fighter. The “Balbo”, the tight bomber formations built on Douhet’s principles, was proved equally costly by the Italian, British, French and German air forces. As none of the parties had an effective early-warning apparatus the interception of bomber raids was often rather incidental and both parties, even if flying and attacking with vigor, could show little results for it, much because of the unstable weather.

The French, with a much smaller available bomber force, scraped the bottom and sent off a mixture of rather old-fashioned Bloch 210s and the ultra-modern Lioré et Olivier (LeO) 45 451, probably the fastest bomber at the time and unique in that it had a 20 mm automatic dorsal-mounted cannon for its rearward defense. One mission flown by six Martin Marylands from Tunis was able to catch a complement of seven Cant Z.501 seaplanes in their hangar at the Elmas airbase, Sicily, where they were assembled for repainting. A direct hit on their hangar rendered six of them destroyed while the seventh was damaged. Some personnel were also killed and the base, in general, received much damage.

This Fiat is being bombed up manually. Not unusual at the time. It was very flexible as to types and sizes of bombs.

As a whole, Mussolini should be quite happy that the French leadership did not decide to pull back to their North African colonies to continue the fight from there. This particularly concerns the air war as a large part of the French Hawk and D.520 fighters were successfully transferred to Algeria and Tunis before France surrendered. The Hawk units had taken more than they gave during the Phony War and had proved more than a match for the Bf109 units of the Luftwaffe. In such a case, as this aircraft type was manufactured by the Curtiss factory in the US, there ought to be a good chance that these could have been maintained in Africa. The same applied to their Martin Maryland bombers and the Navy’s Vought fighters.

The Hawk 75 was a highly maneuverable dogfighter. Substituting it with the P-40 was a huge backward step for the USAAF.

Air War Over Western Desert

When the air fighting started over the western desert the Italians had much larger fighter forces present in the frontline than the British, approximately 50 CR.42 and CR.32’s of the 8th and 10th Stormos (wings). To counter this RAF could only muster the few Gloster Gladiators of the 33rd squadron. But, the British had decided upon an offensive stance and the Blenheims of the 202nd Group started out in grand style on the first day of the war.

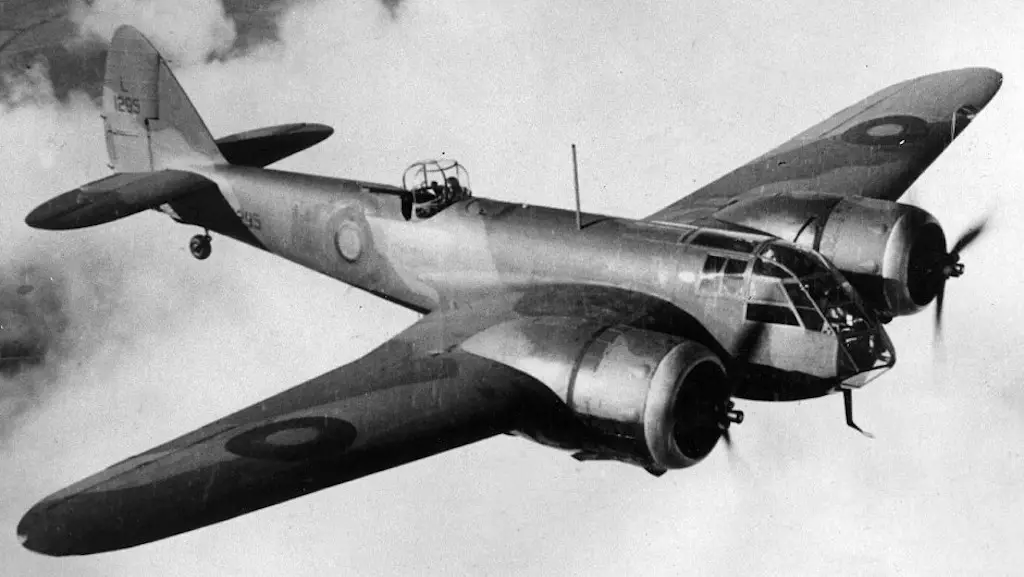

RAF annals state that the attacks on El Adem airfield by 26 Blenheims achieved “some success” without specifying this, which usually means that little was achieved. On the other hand, 3 Blenheims were lost. In an attack later in the day, it was claimed that a total of 18 enemy aircraft were destroyed on the ground. This is not confirmed by Italian sources, the numbers could be approximately halved, a quite common occurrence on all sides, but even then a good result.

According to the British, the Italians seemed unprepared with inferior dispersal of parked aircraft. The following days saw further RAF bombing raids and support of the army for the conquest of Fort Capuzzo. Then they ran out of steam. With the uncertain supply and reinforcement situation Air commodore Collishaw found that his resources had to be harbored and the RAF raids were switched to night-time. The intense operations also uncovered a problem that would only increase for both parties, the abnormal wear and tear on engines and weapons caused by the particular climatic conditions of the Desert. S. O. Playfair recorded in the official history that:

…there was no air filter that would satisfactorily resist the all-pervading sand and dust, with the result that day-to-day serviceability was seriously affected, while the change to coarse pitch of the variable pitch airscrew was often made impracticable. Instruments, too, were so badly affected that it was necessary, soon after war began, to form a special mobile section to service the instruments in the Sqn aircraft. Another serious inconvenient was the blowing-out and cracking of the Perspex panels of the Blenheim aircraft due to distortion from the heat of the sun. All these difficulties and many others, involved so much additional maintenance work that it was found necessary, soon after the war began, to form an advanced repair and salvage section in the Western Desert and to augment the maintenance organization in the Canal Zone.

Bristol Blenheim – RAF workhorse in the Desert 1940.

Regia Aeronautica was a little slower off the blocks. While there were plenty of air defense patrols and bombing operations against small enemy ground units and forward areas, not until the night of 21st/22nd June was Alexandria and the naval storage areas in Aboukir attacked. The results were inconclusive but as a whole, for this period the fast Italian bombers proved a match for the slow Gladiators. They would often climb to intercept the enemy only to see their tails disappear on the horizon. There were some Hurricanes available in theatre but only one was released for duty in the forward area.

…..and the Italian workhorse, the Fiat CR.42.

Battle for Malta

June 11th was also the day of the start of the epic battle for Malta. Already in 1938, the Italian Navy addressed the Italian High Command that a prerequisite for a successful campaign in the Mediterranean was the early occupation of Malta. Plans for such an operation had consequently been worked out by the Navy. The Italian leadership, however, expecting a short war, was not interested in looking closer at this. Also, the air force stated that they could only muster approximately one hundred outmoded aircraft for the purpose.

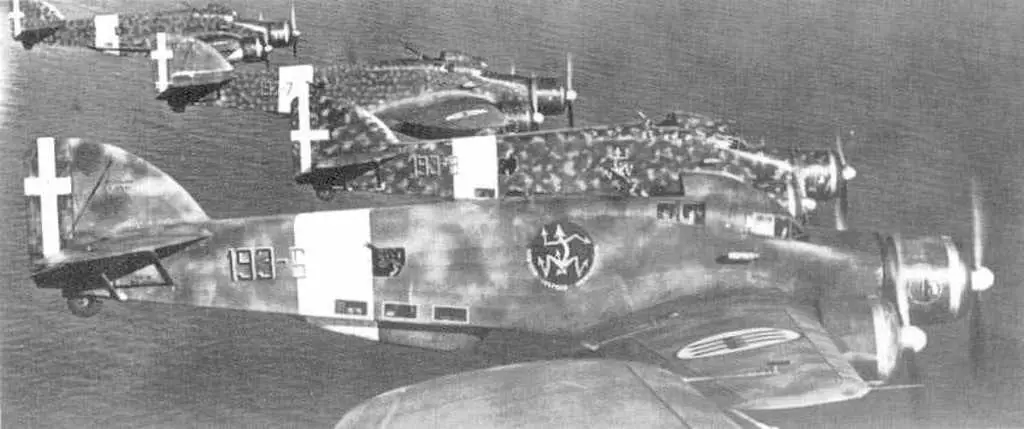

A strange way to put it as, when the war finally broke out, the bomber forces stationed in Sicily and Africa were equipped with some of the most modern aircraft at its time. So, Italy had to learn the lesson that was eventually experienced by all major warring parties, that Douhet’s theories did not hold water, that countries and populations could not be bombed into submission – as long as they did not have a choice, which none of the civilian populations of any of the protagonists had.

Not the Maltese, either. So, bombing it was to neutralize Malta as an enemy base for submarines and naval surface vessels, bombers, and recce aircraft – but no invasion. Luckily for the Allies, Mussolini made the same mistake as his partner-in war, Hitler, when he did not pursue first thing first by invading England before taking on the Soviets.

The Savoia SM.79 – the main bomber of the Malta campaign – very maneuverable as bombers go.

Faith, Hope, and Charity

Few WW2 myths have been trumped-up to such a degree as the initial air defense of Malta. It all centers around three Gloster Gladiator biplane fighters which eventually were given the fictive names of Faith, Hope, and Charity.

That this fighter force came into existence at all was more in spite, than because of, actions were taken by the central British leadership. In the winter of 1940, the total air defense of Malta consisted of some reconnaissance aircraft, some Fairey Swordfish used for target towing and the odd bomber or transport plane calling on for refueling on their way to Egypt or Gibraltar. Eventually, permission was given in March 1940 to assemble 6 FAA Gladiators stored in crates at Malta.

A spirited crew of pilots and mechanics were assembled from various units already at Malta and they soon had the Glads assembled with some local improvisations, familiarization and training were immediately set in motion. This admirable initiative almost came to nothing when new orders arrived: Their Gladiators should be re-cratered and sent to Egypt. Some were shipped to Alexandria but on 29 April a new order stated that the Hal Far Fighter Flight could be reformed with the six remaining planes, led by Flying Officer Collins, RAF.

These six aircraft formed the nucleus that kept three of them flying until the end of June, but rarely simultaneously. The names Faith, Hope, and Charity were never given officially to any of them and spares and parts were readily transferred between them with never-ending improvisations to keep them flying. The most advanced being the installation of various types of three-bladed adjustable propellers, more efficient than original two-bladed wooden ones. One is said to have received a propeller from a stranded Blenheim bomber which is rather peculiar considering the larger size of this. Group Captain George Burges put it like this:

From time to time people refer to the story of ‘Faith, Hope, and Charity’. Reference to Admiralty records proves that there were quite a few other Gladiators on the island when hostilities with Italy started. We were certainly given four aircraft to set up the Hal Far Flight, and there were certainly some others at Kalafrana in crates and from time to time aircraft with other ‘rudder numbers’ appeared to replace casualties. Whether these other aircraft had been completed in their crates I do not know. An enormous amount of improvisation had to go on to keep aircraft operational and a ‘new’ fuselage would have ‘second-hand’ wings or engine. As the ‘rudder number’ was on the fuselage this would seem to be yet another new aircraft. Thus it was only during our training period, before the war started for us, and for only about the first week or ten days of the war period that the population ever saw three Gladiators in the air together – from then on it was two and sometimes only one. During this period none of us ever heard the aircraft referred to as ‘Faith, Hope, and Charity’ and I do not know who first used the description. Nevertheless, the sentiment was appropriate because the civil population certainly prayed for us and displayed such photographs as they could get hold of. There is no doubt that the Gladiators did not ‘wreak death and destruction’ to many of the enemy, but equally, they had a very profound effect on the morale of everybody in the island, and most likely stopped the Italians just using the island as a practice bombing range whenever they felt like it.

So, little death and destruction were dealt by this first Malta fighter defense but they did have a value in breaking up many of the tight Italian bomber formations arriving over the island almost every day. They also had the advantage of an active radar-based ground control system which often made it possible for them to climb to an advantageous attack position before the Italian bombers had reached their targets.

Gloster Gladiator – the Malta myth.

On the evening of 10 June, there were six operational Gladiators with seven pilots that had approximately 80 hours of familiarization between them on the type. None had ever had basic or advanced training on the Gladiator or served in a Gladiator unit. To make a long story short, every day the British fighters went up to attack the ever-present Italian bombers, which were often escorted by the new Macchi MC.200 fighters, expended their ammunition and landed to be ready for new waves of aggressors. Some hits were recorded but hardly an Italian crew member had been wounded when the first Hurricanes arrived on 21 June to assist the Gladiators in their quest. Only on 22 June could George Burges and “Timber” woods chalk up an SM.79 recce plane over Sliema. It went down in the sea off Kalafrana after one of its engines was shot off.

July 3rd saw two “firsts”. The first one, an SM.79, shot down by a Hurricane flown by Flying officer John Waters. The second is the same Hurricane bumped by Major Botto in his CR.42 as Waters was landing back at his base, the first Italian fighter victory over Malta. Waters survived the crash but his Hurricane was a write-off.

It is only fitting to finish this article with two separate incidents that define the professionalism and dedication of the Italian Navy at the time – the destinies of the light destroyer Espero and the submarine Torricelli, the last one taking place in the Red Sea.

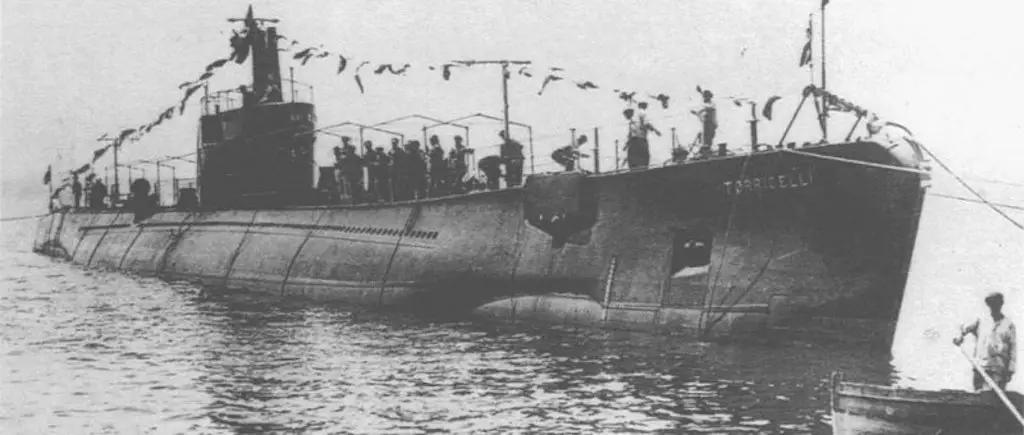

Submarine Evangelista Torricelli

Torricelli, a modern submarine of 1.000 tons displacement of the Brin-class, launched in 1939. It had been patrolling outside Djibouti and was on her way back to Massawa after having received damage which forced her to stay on the surface. She had just passed the Perim Strait, the entrance to the Red Sea from South-East when she was discovered by the RN gunboat Shoreham.

This called for reinforcements and soon Torricelli was pursued by three British destroyers and two gunboats. Lieutenant Commander Pelosi was not one to give up and opened fire first with his 120 mm deck gun and four machine guns. The Brin-class was so constructed as they had their gun on the aft deck, an advantage when pursued. It also had four torpedo tubes aft. The second round hit Shoreham which had to withdraw and return to Aden for repairs. Even with eighteen 120 mm and four 102 mm guns against him, Pelosi kept up the fight for 40 minutes, the range decreasing steadily. Torricelli also fired off her torpedoes but these were evaded. When Pelosi was wounded he ordered Torricelli scuttled and he and his crew were brought to Aden as prisoners-of-war.

RM Evangelista Torricelli – a heroic boat.

On the way there he had the satisfaction of seeing the destroyer HMS Khartoum blowing up, later to be grounded ashore. It was never recovered. The reason for the explosion was an obviously damaged torpedo tube which later caused the warhead of the torpedo inside it to explode. In the RN investigation report, it seems very important for the British not to have this down as a result of a skirmish with a simple Italian submarine. Pelosi and his crew were received with full military honors and the British admiral-in-command in Aden stated that the British had fired off “seven hundred shells and 500 rounds of machine gun ammunition”. Perhaps a little too much military honors. If this information was correct it does not reflect well on the marksmanship of the Royal Navy, but this is confirmed in the following story.

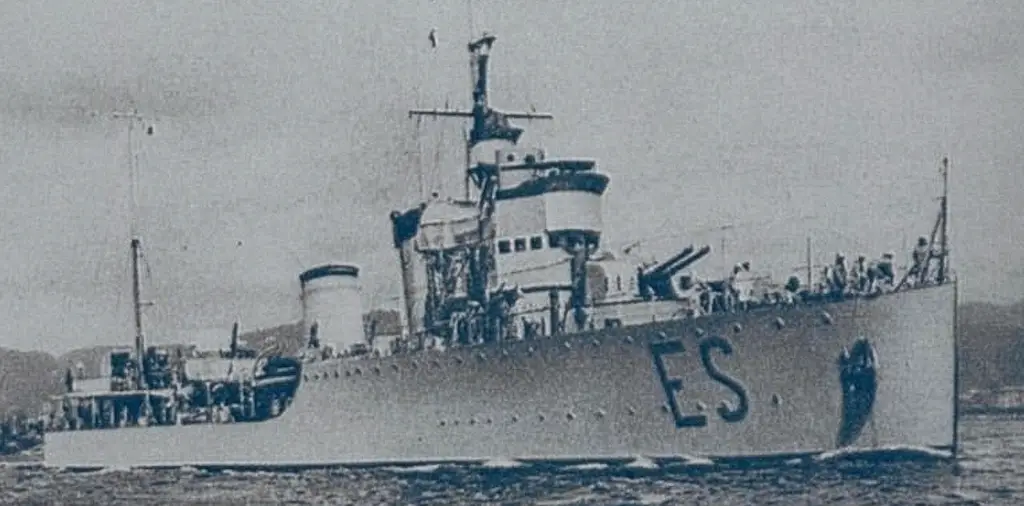

Light Destroyer Espero

A few days later the destroyers Espero, Ostro, and Zeffiro left Taranto loaded with anti-tank guns and their army personnel for the Italian Army in Libya. These were ships of the Turbine-class, all launched at the end of the twenties and quite fast. They were armed with 4 x 120 mm guns and six torpedo tubes.

The morning after, the Italian destroyers were discovered by an RAF Coastal Command recce plane, a Sunderland flying out of Egypt or Malta. It followed them for some time and in the evening, just after 1800, five British cruisers belonging to Admiral Tovey’s 7th cruiser squadron suddenly appeared out of the dark Eastern horizon. They had left Alexandria on the 27th covering convoy AS 1 with destination Port Said from Greek waters.

Fire was opened at approx. 18.000 meters range and they kept this up till Espero was finally sunk by HMS Sydney after 5.000 rounds had been fired by the British cruiser squadron. It took almost an hour before Espero received its first hit and the uneven fight lasted for almost two hours.

In the meantime Espero’s maneuvers, smoke-laying, and return fire had let the two other destroyers off the hook, they escaped unscathed to Benghazi to proceed to Tobruk the day after. 47 survivors from Espero were taken in hand by Sydney which had to break off the rescue effort due to approaching Italian aircraft.

Captain Baroni went down with his ship and was posthumously awarded the Military Gold Medal for Valor – the highest Italian award. An interesting side-effect of this skirmish was that the cruisers HMS Gloucester and Liverpool had to abort their escort mission to return to Alexandria to replenish their ammunition stock and due to a general lack of 6-inch ammunition in the Eastern Med fleet all Malta convoys had to be postponed for two weeks.

Italian destroyer Espero. The Royal Navy cruisers spent 5.000 6-inch rounds to sink her.

The French Armistice

When the month of June was over Mussolini had his thousand dead, wounded and missing that he, according to himself, needed to weigh in at the peace negotiations with France.

As it turned out, this meant little as Hitler showed remarkable restraint in his demands on the French and was able to impress his opinions in this respect on Mussolini. The negotiations, which never proceeded past an Armistice, gave the Axis Powers admittance to the French Atlantic coast and the English Channel, but little more. France should pay reparations and uphold the costs of the German occupation of France while thousands of French prisoners of war were withheld in Germany as a sort of hostages, eventually to be used as forced labor.

Great opportunities to improve on the power balance in the Mediterranean were wasted by this. The Axis powers did not press for bases in French North Africa which would have made the conditions for the Royal Navy in Gibraltar much more complicated and further strangled the maritime transport route through the Mediterranean.

Franco, the Spanish dictator, was not put to the point on his earlier promises that Italy could establish bases in the Balearics in a case of war, and a free road to Gibraltar for the Germans. The French fleet was left alone in Toulon. Hitler’s policy of leaving the French high and dry also dampened the domestic French powers which were not estranged to joining up with the Axis against the British.

There were many French who saw the lack of British engagement during the Battle of France as a minor treason to a brother in arms, especially the Dunkirk debacle where the French wanted to make a stand to offload the coming assault on the Somme line, and the British unwillingness to engage the RAF fully in the battle. These feelings were amplified after the Royal Navy’s attacks on the French navy in Oran in July and Dakar in September. With France out of the fight, Mussolini could orientate his freed-up forces towards the East – Egypt.

The Franco-Italian Armistice