Italian Actions in the Siege of Tobruk

“Always beating against the unbreakable barrier of the Bologna Division”

These are the words of an Italian war correspondent on 1 December 1941, when describing the fighting spirit of Major-General Carlo Gotti’s Bologna Division, which had fought off repeated attacks from the 70th Infantry Division, the largely British garrison defending Tobruk. As part of ‘Operation Crusader’, the 70th Division was meant to have smashed through the 25th Bologna early on 21 November but were unable to break the siege of Tobruk until 10 December. Unable to accept the fact that the Italians had taken and given as good as they got, the myth soon grew that it was actually the Germans rather than the Italians that had frustrated their breakouts attempts on 21, 23, 25 and 28 November. Some have gone so far as to say that the Bologna Division had been relieved by the German Afrika Division and that German soldiers dressed in Italian uniforms were captured in the Italian strong points.

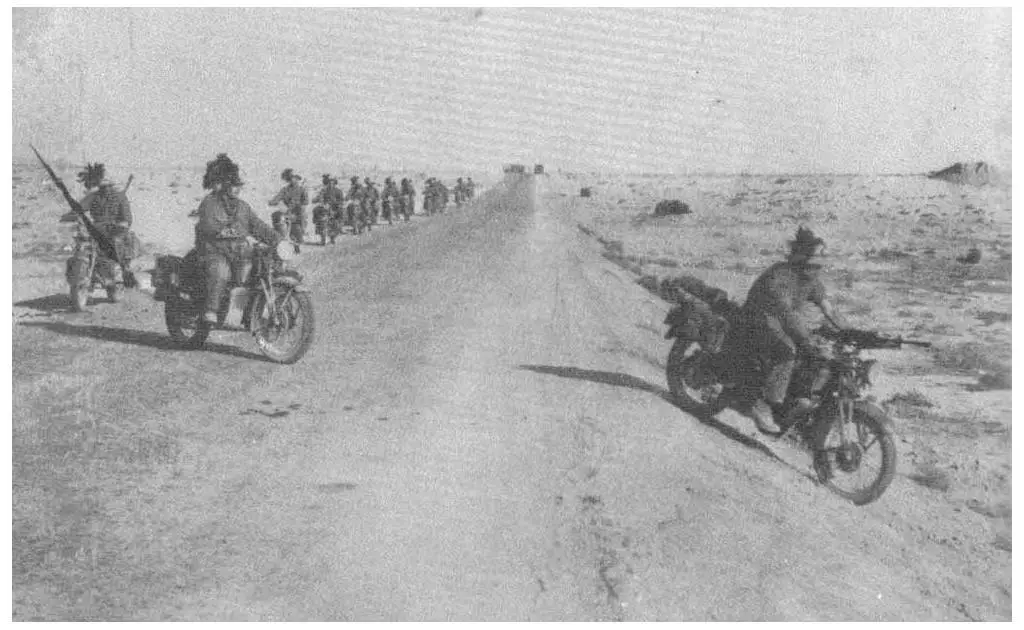

An Italian military convoy on its way to Tobruk, Libya in 1941.

Unheeded Warning from Italians

Thanks to ULTRA code breakers, the British knew all about General Erwin Rommel’s plans to take Tobruk. They launched the offensive “Operation Crusader” two days before Rommel’s own planned attack, catching him completely by surprise. In the week prior the British offensive, General Ettore Bastico, Commander-in-Chief of the Italian High Command in North Africa, had warned Rommel of the coming offensive. But both Rommel and Major Friedrich Wilhelm von Mellenthin, Chief of Rommel’s Intelligence, refused to listen. On 11 November, Mellenthin, discussing the matter with an Italian liaison officer, said: “Major Revetria (Chief of Italian intelligence) is too nervous. Tell him to calm down, because the British are not going to attack.” On 18 November, Lieutenant-General Gastone Gambara, commander of the Italian XX Corps, sent a message to Comando Supremo, “Intercepted enemy messages (radioed in the clear) make us suppose that there is an imminent enemy attack from the south on Sidi Omar and Bir el Gobi.” However, Rommel ignored his Italian counterpart and also ignored air reconnaissance photos showing a major military buildup at Mersa Matruh.

General Ettore Bastico in North Africa warned Rommel of the coming British offensive.

The British Attack

The British attack began on 18 November 1941. The 4th Indian Division began the assault, assaulting the wire north of Sidi Omar, while Lieutenant-General William Gott’s 7th Armoured Division hooked north-west around the southern flank in three powerful tank columns heading towards Tobruk. The aim of “Operation Crusader” was to engage as much German armor as possible outside Tobruk, thus helping the Tobruk garrison to break out through the Bologna sector. General Enea Navarrini’s XXI Italian Corps, the Bologna, Brescia, Pavia Divisions, and elements of the Sabratha Division occupied the siege lines. The British forces initially made good progress, with the 23rd New Zealand Battalion capturing Fort Capuzzo and the 7th Armoured Brigade capturing the Sidi Rezegh airfield, but when the 22nd Armoured Brigade encountered the Italian 132nd Ariete Tank Division deploying near Bir el Gobi on 19 November, it lost 40 Crusader tanks and this attack was aborted at dusk. (Neillands, p. 86) That day, another British column of tanks tried to move westwards towards the track that ran up from Bir el Gubi to El Adem, but there too met determined infantry of the Pavia Division and turned back. (Ford, p. 40) By 20 November, the 7th Armoured Brigade had reached the Sidi Rezegh-Belhamed area, only to find that the only track down the escarpment overlooking the plain before Tobruk had been blocked by the 1st Battalion, 39th ‘Bologna’ Infantry Regiment with the 73rd anti-tank company. The Australian Official History noted, “A powerful artillery group, with a battalion of Italian infantry of the Bologna Division for protection, was established on the escarpment near Belhamed; throughout the 20th it harassed the British.”

Ken Ford has written that:

“The tanks of the 6th RTR fared less well, for as the regiment crossed over the track and passed Sidi Rezegh, its tanks were hit by German and Italian anti-tank guns.” (Operation Crusader: Rommel in Retreat, Ken Ford, p. 48)

In this action, 24-year-old Corporal Reginaldo Rossi of the 39th Bologna Infantry Regiment won posthumously the Medaglia d’Argento al Valore Militare, Italy’s second-highest military decoration. His Silver Medal for Valour citation reads:

As an anti-tank gunner, he was an example to all for his discipline and the care and maintenance he took of the unit’s weapons. In the bloody and arduous combat that took place against numerous armored vehicles, he showed complete and total disregard to the danger present and with absolute calmness, he stuck to his gun that he refused to abandon, even when he found himself surrounded by the enemy.

Reginaldo Rossi monument in Roccagorga, Italy

In his hometown of Roccagorga, Italy, a carefully maintained monument in memory of this Italian war hero survives to this day.

Strong Italian opposition at Tugun

On the evening of November 20, General Sir Ronald Scobie, commander of the British 70th Infantry Division defending Tobruk and its perimeter, ordered a breakout. He said: “Our task is to drive a corridor from the perimeter to the Axis road, which we hope to cut at El Duda. There we should meet the South Africans.” Although the main Tobruk garrison attack on 21 November was to be made by the 70th Division (2nd/King’s Own, 2nd BlackWatch, 2nd/Queen’s and 4th RTR with Matilda tanks), the Polish Carpathian Brigade was to mount its own diversionary attack in the predawn darkness in order to keep the Pavia Division occupied. The attacks were to be preceded by a massive artillery bombardment. During the first day, one-hundred guns would plaster the Bologna, Brescia and Pavia positions on the Tobruk perimeter with 40,000 rounds. (Alexander G. Clifford, p. 191) Initially, the Italians were stunned by the massive fire and a company of the Pavia was overrun in the predawn darkness, but resistance in the Bologna gradually stiffened and in the western half of the ‘Tugun’ strong point, the attack was held all day. Finally, through sheer determination, the British attackers were slowly worn out and in the words of the New Zealand Official History, “The more elaborate attack on Tugun went in at 3 p.m. and gained perhaps half the position, together with 256 Italians and many light field guns; but the Italians in the western half could not be dislodged and the base of the break-out area remained on this account uncomfortably narrow.” Indeed, the New Zealand Official History reports that the “strong Italian opposition at Tugun” was part of the reason why the British attack was abandoned. Lieutenant Ennio Goduti of the 40th Bologna Infantry Regiment was killed manning an anti-tank gun as he resisted the British tanks on this sector. He was awarded a posthumous Medaglia d’Oro al Valor Militare, Italy’s highest decoration for valor. Indeed, the Italians had fought well and the Italian Armed Forces issued the following joint communique on 22 November: “Repeated enemy attempts to break out from Tobruk failed, owing to the work of Italian divisions which besiege the fortress.”

Soldiers of the Pavia Division in an advanced position.

That day, 21 November, another fierce action was fought with high casualties by elements of the German 155th Rifle Regiment, Artillery Group Bottcher, 5th Panzer Regiment and the British 4th, 7th and 22nd Armoured Brigades for possession of Sidi Rezegh and the surrounding height in in the hands of Italian infantry and anti-tank gunners of the Bologna.

During the next two days, 22 and 23 November, the frontier garrisons of Omar Nuovo, Libyan Omar, and Fort Capuzzo fell to infantry attacks spearheaded by two squadrons from 42 RTR and one from 44 RTR, and the New Zealanders cut off the Bardia garrison’s water supply. Many of the Italians fought hard. According to the Indian Express account of the fighting, “It was a most gallant affair, carried out with complete disregard to casualties. The Italians did not give in until our troops were amongst them with bayonets. A minimum of 1,500 prisoners were taken, some of whom were Germans, but the majority of whom belonged to the Italian Savona Division.” (The Indian Express, 26 November 1941) A study of the U.S. War Department concluded: “All Italians captured between 22 November and 23 November in the Omars belonged to the Savona Division and were reported to be tougher on the whole and better disciplined … The [Italian] prisoners were all well-clothed, well-disciplined group, who had put up a good fight and knew it. The 6 German and 52 Italian officers, as well as the 37 German technicians, were very bitter about their capture and would not speak.”

In the meantime, the fighting in the Bologna sector continued, and the 2/Yorks & Lanes, with the 1st RHA in support, took the ‘Lion’ strong point on 22 November, but efforts to clear the ‘Tugun’ and ‘Dalby Square’ strong points were repelled. In the fighting on the 22nd, the ‘Tugun’ defenders brought down devastating fire, reducing the strength in one attacking British company to just thirty-three all ranks.

The ruins of Fort Capuzzo.

The Italian Pavia Division was committed for a counterattack

On 23 November, the 70th Division in Tobruk launched another major attack against the 25th Bologna in an attempt to reach the area of Sidi Rezegh, but elements of the Pavia Division soon arrived and smashed the British attack as a German post-war report recorded:

“After a sudden artillery concentration the garrison of Fortress Tobruk, supported by sixty tanks, made an attack on the direction of Bel Hamid at noon, intending at long last unite with the main offense group. The Italian siege front around the fortress tried to offer a defense in the confusion but was forced to relinquish numerous strong points in the encirclement front about Bir Bu Assaten to superior enemy forces. The Italian “Pavia” Division was committed for a counterattack and managed to seal off the enemy breakthrough.” (See Generalmajor Major Alfred Toppe (et al), German Experiences in Desert Warfare During World War II, in 2 volumes, Combat Studies Institute/Combined Arms Research Library, 1952)

Near the end of the action, the 15th Panzer Division and the 5th Panzer Regiment moved onto Sidi Rezegh and later the Ariete and 8th Bersaglieri came up in support to deal with the 5th South African Brigade in the area. The Sidi Rezegh attack started well but was heavily counterattacked in the evening and although this was repulsed, the loss of 45 German and 11 Italian tanks was worrying. The British 4th Armoured Brigade was reduced to some 12 tanks, however, the aim of the operation had been successful and some 2,300 South Africans were able to escape. (Alexander G. Clifford, p. 161)

Italian Fiat M13/40 tanks in formation.

A British newspaper reported that:

“The full story is now known of the valiant part played by the 5th South African Brigade in the fighting around Sidi Rezegh. These troops recaptured Sidi Rezegh on Friday but were forced to withdraw on Saturday evening. On Sunday they beat off attacks from tanks, artillery, and infantry. The German tanks came on seven abreast and ten deep, and the South African anti-tank gunners fired until their ammunition was exhausted, and knocked out tank after tank. The South Africans were being rounded up as prisoners when British tanks broke through and engaged the enemy just long enough for the South Africans to withdraw.” (Forces Outside Tobruk Now Progressing Westwards, Evening Post, 29 November 1941)

Some Commonwealth prisoners of war taken in North Africa, November 1941.

By 23 November, the Ariete, Trieste, and Savona had probably accounted for around 200 British tanks and a similar number of vehicles disabled or destroyed. (Of Myths and Men: Rommel and the Italians in North Africa, James. J. Sadkovich, pp. 298-299) Certainly, the Axis accounted for more than 350 tanks destroyed and 150 severely damaged between 19-23 November. (Samuel W. Mitcham, p.550) A German communique on the night of 23 November reported that German and Italian troops had destroyed over 260 tanks and 200 armored cars between 19 and 23 November and that on 23 November the “surrounding Italian forces repelled strong attacks by the British garrison at Tobruk, which were supported by tanks.”

On 24 November, Rommel ordered the 15th and 21st Panzer Divisions eastwards to attack the British near the Egyptian border and to give support to his frontier garrisons, in a maneuver that James J. Sadkovich says ‘Rommel lost contact with the German and Italian commander in the Tobruk front for four days.” Rommel hoped to relieve the siege of Bardia and pose a large enough threat to the British rear echelon for “Operation Crusader” to be scrapped. His decision was based on the fact that the 7th Armoured Division had been defeated, but he ignored intelligence reports of British supply dumps lying on his path on the border and this was to cost him the battle. As Oberstleutnant Fritz bayerlein, the chief of staff of the Afrika Korps said after the war, “If we had known about those dumps we could have won the battle.”

Captain Sergio Falletti, a company commander with the 27th Pavia Infantry Regiment was killed on the 24th after calling down artillery and mortar fire from a strong point, during a British attack. The Italian captain was awarded posthumously the Medaglia d’oro al Valore Militare (Gold Medal for Valour) for his efforts to contain the British breakout. The posthumous citation noted that “although mortally wounded by machine gun fire, he didn’t hesitate in calling in artillery and 81mm mortar fire on his strong point, now occupied in part by the enemy.”

The only enemy penetration was brought to a standstill by an Italian counterattack

On 25 November, heavy fighting flared up again on the Tobruk front. In the 102nd Trento Infantry Division’s sector, the 2nd Battalion Queens Royal Regiment attacked the ‘Bondi’ strongpoint but were repelled in heavy fighting. Indeed the defenders fought extremely well and ‘Bondi’ was not be evacuated by the ‘Trento’ until the Axis general withdrawal two weeks later. In the meantime, the ‘Tugun’ defenders (reduced to half their strength and exhausted and low on ammunition, food, and water) surrendered on the evening of 25 November, after much fighting in the predawn darkness. Second Lieutenant Ben Thomas was in Tobruk at the time and witnessed the final charge on their position:

“These forty-five men just walked slowly towards Tugun armed only with rifles, a Bren gun or two and some hand grenades. One hundred yards, 200 onwards up to about 300 yards from the enemy before they let loose. Here and there a man went down, hit or taking temporary cover.”

In the night fighting on the 25th, when his platoon holding part of the ‘Grumpy’ strong point had suffered serious casualties and was being overrun by British troops supported by tanks, Lieutenant Gildo Cuneo of the 39th Bologna Infantry Regiment, together with the remnants of his platoon, resorted to the use of grenades, having run out of ammunition. Together they broke up a number of attacks, before being overwhelmed and the platoon commander bayoneted. Lieutenant Cuneo was posthumously awarded the Gold Medal for Valour.

While the German Böttcher Group was desperately fighting to contain the British tank attacks in the Bologna sector, Generals Navarrini and Gotti got together a battalion of Bersaglieri from the Trieste Division and used them to repulse the British breakout from Tobruk.

Afterwards, Oberstleutnant Bayerlein wrote that:

“On the 25th November heavy fighting flared up again at Tobruk, where our holding force was caught between pincers, one coming from the south-east and the other from the fortress itself. By mustering all their strength, the Boettcher Group succeeded in beating off most of these attacks, and the only enemy penetration was brought to a standstill by an Italian counterattack.”

Bersaglieri firing on Commonwealth forces in North Africa.

From 26-27 November, in a determined attack, the 70th Division killed or winkled out the defenders of several Italian concrete pillboxes before reaching El Duda. On 27 November, the 6th New Zealand Brigade fought a fierce battle with a battalion of the 9th Bersaglieri Regiment, who have dug in themselves in among the Prophet’s Tomb, used their machine guns very effectively. Despite fierce opposition, the New Zealand brigade managed to link up with the 32nd Tank Brigade at El Duda. The 6th and 32nd brigades secured and maintained a small bridgehead on the Tobruk front but this was to last for five days. By 28 November, the Bologna had regrouped largely in the Bu Amud and Belhamed areas and the division was now stretched out along 8 miles from Via Balbia to Bypass Road, fighting in several different places.

The Reuters correspondent with the Tobruk garrison wrote on the 28th that “The division holding the perimeter continues to fight with utmost bravery and determination. They are stubbornly holding small isolated defense pits, surrounded with barbed wire. ” (The Indian Express, 2 December 1941) Nevertheless, it is claimed in the Allied press that the 25th Bologna Division had been effectively destroyed as a fighting unit with a Cairo spokesman reporting: “We’re forging ahead south-east of Tobruk and have eliminated practically all the Bologna division covering the eastern end of the Tobruk perimeter.” (LINK WITH TOBRUK STRENGTHENED. The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 November 1941)

On 29 November, in an official communique, the Italian High Command denied this, saying that the latest British attempts to break through the Italian siege lines had been defeated by men of the 25th Bologna. (ROME SAYS BRITISH BRIGADE DESTROYED, Toledo Blade, 29 November 1941) At this stage of the fighting, the Bologna Division had taken such losses in its attempt to contain the Tobruk garrison that a lesser commander might have called it quits.

That day, 29 November, the 132nd Ariete Division (and accompanying 3rd and 5th Bersaglieri Motorcycle Battalions under Majors Cantella and Gastaldi) overran the 21st New Zealand Battalion along with the New Zealand field hospital which included the prisoner of war cage. (Kay, p.37) The Italians were reported to have captured some 200 hospital guards, along with 1,000 wounded and 700 medical staff. They also freed some 200 Germans being held captive in the enclosure on the grounds of the hospital. (Greene & Massignani, pp. 121-122) The 21st New Zealand Battalion suffered some 450 killed, wounded and captured in what turned out to be a very bleak day for the 5th New Zealand Division.

Bersaglieri riding Moto Guzzi motorcycles in North Africa during the siege of Tobruk.

Lieutenant-Colonel Howard Kippenberger, wounded and a prisoner in the hospital later wrote:

“About 5.30 p.m. damned Italian Motorized Division (Ariete) turned up. They passed with five tanks leading, twenty following, and a huge column of transport and guns, and rolled straight over our infantry on Point 175.”

The New Zealand Official History mentions the capture of 1,800 patients and medical staff members, but maintains they were captured by the Germans:

“The cooks were preparing the evening meal in the grouped MDSs on 28 November [sic] when over the eastern ridge of the wadi appeared German tracked troop-carrying vehicles, from which sprang men in slate-grey uniforms and knee boots, armed with Tommy guns, rifles, and machine guns. ‘They’re Jerries!’ echoed many as the German infantrymen ran down into the wadi and as if to show that they did not intend to be trifled with, fired a few bullets into the sand.”

The New Zealand Official History goes on to comment that on 29 November:

“Columns of Italian transport passed through the lines westwards, and during the night the clatter and rumble of mechanized vehicles continued around the southern end of the wadi.”

On 30 November, despite counterattacks on the Tobruk front, the ‘Leopard’ strong point was taken. It was during this fighting that Lieutenant Francesco Coco of the 28 Pavia Regiment, although wounded, led the remnants of his company in an attempt to retake ‘Leopard’. For his brave action, the Italian officer was awarded the Gold Medal for Valour posthumously.

Italians passed to counter-attack along the whole line

On 1 December, the 2nd New Zealand Division was forced to give up Sidi Rezegh as the Germans broke through its positions and the Trieste cut the tenuous link established with Tobruk,(Christopher Chant, p.37) while the British 4th Armoured Brigade retreated to the south and regrouped in the Bir Berraneb area. (Brigadier R. M. P. Carter, p.24)

On 1 December, a Reuters correspondent with the Eighth Army announced that the Bologna Division had finally been destroyed. He wrote:

“When the Tobruk garrison sortied to joining up with the relieving troops, they made mince-meat of the Italian Bologna Division which held positions on the eastern sector of the Tobruk perimeter. It is now confirmed that the Bologna division has been virtually wiped out as a fighting force.” (Italian Bologna Division Wiped Out, The Indian Express, 2 December 1941)

But the Bologna Division, along with the Trento and Pavia, continued to hold their ground, and on 1 December, an armored attack was reportedly beaten back in the Trento sector. (See New York Times, 2 December 1941) On 2 December, General Navarrini’s Order for the Day about the fighting noted:

“Since the beginning of the present gigantic fighting, the Trento has offered an impassable wall of steel to all the desperate attacks of the enemy, delivering lightning blows which have once more snatched the initiative from the enemy’s hands. Now that definite victory seems to be at hand, it continues to fight.”

On 4 December, the Pavia and Trento Divisions launched counterattacks against the 70th Division in an attempt to contain them within the Tobruk perimeter and reportedly recaptured the ‘Plonk and ‘Doc’ strong points. (The New York Times, 5 December 1941; J. L Ready, p. 313)

Pavia division inspecting a British A9 Cruiser tank pressed into Italian service.

On 6 December, Rommel ordered his divisions to retreat westwards, leaving the Savona to hold out as long as possible in the Sollum-Halfaya-Bardia area. They did not surrender until 17 January 1942.

That night, the 70th Division captured the German-held ‘Walter’ and ‘Freddie’ strong points without any resistance, however one Pavia battalion made a stand on Point 157, inflicting heavy casualties on the 2nd Durham Light Infantry with its dug-in infantry before being overrun, leaving behind some 130 prisoners.

Now began an Italian retreat towards the Gazala Line. On 8 December, after 20 days of heavy fighting, the 25th Bologna was ordered to withdraw from the front line, having suffered 30 percent casualties and winning two Gold and at least one Silver medals in the process. They may have been green and under-strength battalions, but they had held out long enough for the Pavia, Trieste and Boettcher Group to arrive and plug the gaps.

On 10 December, the British 70th Division finally managed to break out from Tobruk and after a fierce but intense battle, the Polish brigade finished off the Brescia rearguards, capturing Acroma on the 10th. This attack effectively lifted the siege of Tobruk after 255 days. (Jack Greene & Alessandro Massignani, p. 126)

The Bologna, Brescia, Pavia, Trieste, Trento, and DAK held the Gazala line from 10-13 December. The German commanders soon realized that the Allies would sooner or later break through the defenses and Rommel decided to pull his seasoned troops back to Mersa Brega and El Agheila. On 14 December, the Italians woke up only to find the Germans had abandoned them.

Historian J. L. Ready wrote in the book The Forgotten Axis that:

“On the night of the 13th Rommel ordered another withdrawal, and now the animosity between German and Italian broke into conflict. In several cases, Germans who had no vehicles stole Italian vehicles at gunpoint, and some German battalions stealthily crept out of the line without bothering to notify let alone coordinate with, the Italians on the flank. The sun had risen before some Italians learned of the retreat. This meant that much heavy equipment was left behind, including precious anti-tank guns, and tens of thousands of Italians began walking across a flat desert swept by a cold wind under the eyes of every pilot in the Allied air force.”

Rommel now had an argument with Generals Bastico and Gambara over his decision to withdraw the German troops. That day, as the 15th Panzer Division was ordered to return to the assistance of the Italians, an infantry battalion of the Pavia Division was overrun and the battalion commander, Major Giuseppe Ragnini was killed in desperate fighting. Major Ragnini, who led a counterattack on 4 December with his battalion and reportedly captured 137 prisoners, was awarded posthumously the Gold Medal for Valour.

On 15 December, the Brescia and Pavia, with Trento in close support, repelled a strong Polish-New Zealand attack, thus freeing the German 15th Panzer Division which had returned to the Gazala Line, to be used elsewhere. Richard Humble writes:

“The Poles and New Zealanders made good initial progress, taking several hundred Italian prisoners; but the Italians rallied well, and by noon it was clear to [General Alfred] Godwin-Austen that his two brigades lacked the weight to achieve a breakthrough on the right flank. It was the same story in the center, where the Italians of ‘Trieste’ continued to repulse 5th Indian Brigade’s attack on Point 208. By mid-afternoon, the III Corps attack had been fought to a halt all along the line.”

Of the fighting on the Gazala Line on 15 December, the Italian High Command communique said merely that:

“Enemy pressure continued at El Gazala and met with vigorous Italian resistance. Italians passed to counter-attack along the whole line“. (The New York Times, 16 December 1941 )

M13/40 medium tanks moving forward in North Africa.

So, on the afternoon of 15 December, the Ariete with some 30 M13’s and with Bersaglieri motorcycle troops in close support, counterattacked along with the remaining 23 tanks of the 15th Panzer Division, and the attack was successful as the 1st Battalion, The Buffs (Royal East Kent Regiment) and other troops of the 5th Indian Brigade lost over 1,000 men killed, wounded or taken prisoners. (Greene & Massignani, p 126; Ronald Lewin, p. 93)

On 16 December, the Deputy Commander of the 102nd Trento, Brigadier-General Giulio Borsarelli di Rifredo, was reportedly killed in an Allied air attack on the Gazala Line. He had been in overall command of the Trento briefly, as the actual commander, Major-General Luigi Nuvoloni was needed elsewhere in the fighting. He was Italy’s seventh general to be killed so far in the war. (7th Italian General Dies, The Baltimore Sun, 24 December 1941)

On 16 December, a Rome communique reporting on the capture of ‘the Buffs on the 15th claimed that:

“Italian motorized and armored divisions with the support of large German units fought with extreme tenacity and inflicted heavy losses on the enemy. Many armored units were set on fire and destroyed. Prisoners were numerous and included a brigade commander“. (The New York Times, 17 December 1941 )

The ‘brigade commander’ mentioned above, was in actuality the commanding officer of ‘the Buffs’, a full colonel who had been wounded in the action and is reported to have said in his last report to divisional headquarters, “I am afraid this is the last time I shall speak to you. They are right on top of my headquarters now.” (Alexander G. Clifford, p. 205)

General Fedele de Giorgis’ 55th Savona Infantry Division did not surrender until 17 January 1942. Of the commander of the Italian division, Rommel reported, “Superb leadership was shown by the Italian General de Giorgis, who commanded this German-Italian force in its two months’ struggle.”

The fighting had, at last, come to an end. The Axis forces suffered 2,300 killed (1,200 Italians and 1,100 Germans), 6,100 wounded (2,700 Italians and 3,400 Germans) and 29,900 captured (19,800 Italians and 10,100 Germans), compared with British and Commonwealth losses of 2,900 killed, 7,300 wounded and 7,500 captured.

Italian tank at full speed near Gazala.

Rommel, of course, blamed the Italians for losing the battle, and Generalmajor Ludwig Crüwell criticized Gambara for not rousing into action the exhausted Italians on 6 December.”Where is Gambara?”, he is reported to have mockingly said that day “in clear” to Rommel repeatedly. But the truth of the matter is that he had himself disregarded an order from Rommel to deliver a knockout blow against the New Zealanders in the early fighting on the Tobruk front, saying that his men were too tired and without provisions to be able to carry out the mission, even though radio intercepts would’ve told him that the New Zealanders holding the Tobruk corridor were running desperately low on ammunition. Nor should one overlook the fact that the Italian soldiers in North Africa had nothing to sustain them in the fighting, but their regimental pride and patriotism. On the other hand, the The Deutsche Afrika Korps (DAK), supplied with luxuries such as genuine coffee beans, wine and beer, reportedly took energy tablets and performance-enhancing drugs to to keep them going, such as the 100,000 amphetamine tablets that Rommel is reported to have issued out to German units in time for the final showdown at Alamein. (Alexander G. Clifford, p.196; Nicolas Rasmussen, p.70) This in no way diminishes the fighting spirit and achievements of the DAK, but helps put things in perspective, however annoying it may be to some.

Article By: David Aldea (anurom@hotmail.com) and Joseph Peluso (giupel@inwind.it)

Joseph Peluso is a graduate accountant but now retired. A former boy scout, he hasn’t given up that passion and is now a scout leader for adults. He is also a military history buff fascinated with the role of the 25th “Bologna” Motorised Division in North Africa. He is currently writing a book about his father, Carmine Peluso who served in the 40th “Bologna” Infantry Regiment as an NCO and was decorated.

References

The Desert Rats: 7th Armoured Division 1940-45, Robin Neillands, p. 86, Aurum Press Ltd, 2005;

Operation Crusader 1941: Rommel in Retreat, Ken Ford, p. 40, Osprey Publishing, 2010;

The Conquest of North Africa 1940 to 1943, Alexander G. Clifford, pp. 161,191 & 196, Kessinger Publishing, 2005;

Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War, 1939-45: The Relief of Tobruk, Walter Edward Murphy, p.94, War History Branch, 1961;

German Experiences in Desert Warfare During World War II, in 2 volumes, Generalmajor Alfred Toppe and 9 others, Combat Studies Institute/Combined Arms Research Library, 1952;

Of Myths and Men: Rommel and the Italians in North Africa, James J. Sadkovich, pp. 298-299, The International History Review, 1991;

The Rise of the Wehrmacht, in 2 volumes, Samuel W. Mitcham, p.550, Praeger 2008, The Longest Siege: Tobruk-The Battle that saved North Africa, Robert Lyman, p.269, Macmillan, 2009;

Inside The Afrika Korps: The Crusader Battles, 1941-1942, Rainer Kriebel & Bruce Gudmundsson, Greenhill Books, 1999;

Rommel’s North Africa Campaign: September 1940-November 1941, Jack Greene & Alessandro Massignani, pp. 116, 121, 126 & 122, Da Capo Press, 1999;

The Rommel Papers, Basil H. Liddell Hart et al, pp. 167-168, De Capo Press, 1953;

The Life and death of the Afrika Korps, Ronald Lewin, p. 113, Quadrangle/New York Times Book Co, 1977;

Chronology, New Zealand in the War, Robin Kay, p.37, Historical Publications Branch, 1968;

Infantry Brigadier, Howard Kippenbergerp, 101, Oxford University Press, 1949;

The Encyclopedia of Codenames of World War, Christopher Chant, p.37, Routledge & Kegan Paul Books Ltd, 1987;

The History of the 4th Armoured Brigade, Brigadier R. M. P. Carter, p.24, Merriam Press, 2000;

The Forgotten Axis: Germany’s Partners and Foreign Volunteers in World War II, J. L. Ready, pp. 313-314, Jefferson,1987;

Crusader: Eighth Army’s Forgotten Victory, November 1941-January 1942, Richard Humble, p. 187, Leo Cooper, 1987;

Rommel as Military Commander, Ronald Lewin, pp. 71 & 93, Barnes & Noble Incorporated, 1998;

Salute to Service, A History of the Royal New Zealand Corps of Transport and its Predecessors, 1860-1966, Julia Millen, Victoria University Press, 1997

On Speed: The Many Lives of Amphetamine, Nicolas Rasmussen, p.70, New York University Press, 2008)