In early July 1940, the Italian navy high command conceived the idea to dispatch a group of light cruisers in the Aegean Sea to intercept British convoys in the eastern Mediterranean. The task was given to the II light cruiser division formed by the Ships “Giovanni Dalle Bande Nere” and “Bartolomeo Colleoni. The two ships belonged to the “Giussano” class and were characterized by good armament (4×2 152mm guns) and great speed (35–36 knots) although at the cost of protection, which was extremely weak for a light cruiser. These ships were the first generation of Italian light cruisers developed in the late 1920s and suffered from several design flaws, partially solved by 1940. The II division, stationed in Tripoli, left the harbour on the 17th July, Admiral Casardi had the order to attack British merchant ships in the area northwest of Crete and then reach the Italian base of Leros in the Dodecanese.

The Command of the Mediterranean Fleet (of the British Royal Navy) knew nothing of the Italian operation but some warships were in the area because of other operations scheduled for the morning of the 19th July. These operations were aimed at countering the activity of Italian submarines and for this, the destroyers HMS Hyperion, Ilex, Hero and Hasty were deployed in the area northwest of Crete. Simultaneously, a second force (under captain John A. Collins) constituted by the Australian light cruiser HMAS Sydney and destroyer HMS Havock was patrolling the more to the east, in search of Italian transport ships re-supplying the Dodecanese bases.

The Italian aircraft deployed on those islands flew recognisance missions on the 18th of July and sighted no allied surface vessels, thus re-assuring Admiral Casardi. The reconnaissance flights scheduled for the morning of the 19th were delayed due to adverse weather conditions, thus failing to alert Casardi of the allied presence in the area.

That same morning, at 06:17, the II division, sighted the 2nd destroyer flotilla HMS Hasty, Hyperion, Hero and Ilex in the sea zone north-west of Crete (near Cape Spada). The Italian Ships opened fire on the British destroyers which found themselves outgunned with their 120mm guns against the 152mm guns of the Italian light cruisers. After 30 minutes of fire exchange, the British ships turned North in what seemed to be a retreat to escape enemy fire while the Italian formation started the pursuit. The 2nd destroyer flotilla was trying to link up with Captain Collins group formed by the Australian cruiser Sydney and the destroyer Havock which were steaming south to provide support.

The cruiser Colleoni in navigation

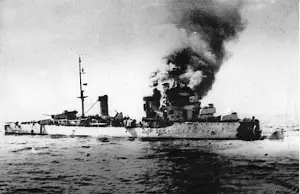

At 07:30 the Sydney group sighted the Italians and open fire together with the other ships. The cruiser Bande Nere received a hit to the seaplane hangar while an Italian shell hit the funnel of HMAS Sydney but caused no severe damage. After around 20 minutes of fire exchange, Admiral Casardi realized that he was facing superior British forces and thus turned 90° degrees south to escape enemy fire. At 08:23, while retreating, a 152mm shell from the Sydney exploded on the Colleoni, devastating the engine room and causing the ship to halt while fires started to erupt on board. A few minutes later, a torpedo launched by the British destroyers blew up the bow of the crippled cruiser.

The HMAS Sydney

Admiral Casardi on the Bande Nere managed to escape, although a second hit reached his ship causing a reduction of speed to 29 knots.

Later in the morning, around 11:30, the British destroyers were attacked by Italian bombers coming from Rhodos and slightly damaged the HMS Havock. The bombers arrived 4 hours after the initial request for aerial intervention made by Casardi.

Captain Umberto Novaro, commander of the Colleoni, was rescued by the British together with other 554 survivors, his ship was then finished off by torpedoes and quickly capsized. Novaro died 4 days later due to the wounds suffered and was buried in Egypt by the British with full military honours.

The crippled cruiser Colleoni (1)

The crippled cruiser Colleoni (2)

The clash of Cape Spada, although being a small action in the Mediterranean theatre, led the Italian navy high command to abandon the idea of deploying a consistent and stable naval presence in the Dodecanese bases of the Aegean to harass allied convoys.

Sources

Giorgernini, G. (2001). La Guerra Italiana sul mare, La marina tra vittoria e sconfitta 1940-1943.

Rocca, G. (1987). Fucilate gli Ammiragli.