At the beginning of 1943, the Tunisian campaign entered a new phase, where the Axis forces launched their last offensive punches on African soil.

The Last Axis Offensives in Tunisia (January-March 1943)

The Axis forces in Tunisia

At the end of 1942, the Allies had lost the so-called “Race for Tunis”, following the establishment and consolidation of the Axis bridgehead in northern Tunisia. However, the overall situation of the Italian and German forces in the theatre remained a precarious one.

January 1943 saw limited clashes between the opposing armies, but more decisive fights were about to come.

To the south, the remnants of the Italo-German Panzerarmee Afrika had retreated from El Alamein to Tunisia in the space of roughly three months, reaching the Mareth line by the end of January. This was an old French defensive line, abandoned in 1940.

In early February 1943, the situation of the Axis forces in Tunisia was the following.

The 5th Panzer Army under General Von Arnim occupied Northern and Central Tunisia. These forces had been rashly transferred via air and sea in the previous months and stretched from Tunis and Bizerte in the north, down to the Sfax and Gabès area.

This Army included the German 10th and 21st Panzer divisions, the 334th Infantry division, the Italian Superga and Centauro divisions, the 50th Special Brigade (a mechanized formation), and many other smaller units including San Marco Marines, Arditi, Fallschirmjagers, Bersaglieri and paratroopers of the Italian air force. A total of 105.000 men and 464 tanks.

In the south, Rommel relied on the veteran divisions of his previous campaigns, although severely depleted after El Alamein and for the long retreat. These were the 15th Panzer, 90° light, and 164° Infantry divisions. The Italian units under his command were the Giovani Fascisti division, the motorized Trieste division, and the recently transferred Pistoia and Spezia infantry divisions. In total, 125.000 men and 123 tanks.

The situation in February 1943

The strategic dilemma

Rommel’s forces were setting up their defenses on the Mareth line, improving the old French emplacements, awaiting the arrival of Montgomery’s 8th army from Tripolitania.

However, the rear of the Panzerarmee Afrika was threatened by the American forces stationed in central Tunisia, which were in the position to launch an assault towards the sea that could have cut off Rommel from Von Arnim’s 5th Panzer army. In addition, the Axis forces would have been unable to face a contemporary Allied assault from the west and the southeast.

German and Italian generals therefore saw the need to launch an attack that would have pushed back the Americans, before Montgomery had gathered his forces for a frontal assault of the Mareth line.

In addition, the Axis command structure was about to change, given the new reality on the field and the size of the forces available. The Army Group Africa was going to be created gathering the 5th Panzer Army and the 1st Italian Army (the new name of Panzerarmee Afrika) with General Giovanni Messe in command of this latter formation. By this point, everybody agreed that Rommel had to leave, but the time was about to come.

Despite the bold offensive plans, it was clear to all high-ranking commanders that the situation was dire and there were no solutions on the horizon. Rommel believed that the two armies had to be evacuated in a kind of “Axis Dunkerque”, the Italians wanted to keep a foothold in Africa, hoping to delay any direct attack the mainland Italy.

Mussolini hoped to reverse the situation by pushing back the Allies, but this was only possible (according to him) if the Germans had committed more reinforcements to the theatre. By this point, the Italian economy was no longer able to keep up with the war demands. To this end, Mussolini was urging Hitler to seek a separate peace with the Soviet Union that would have freed up German forces for the struggle against the Western Allies.

On the contrary, Hitler considered the Mediterranean just a sideshow, and he was already thinking about his upcoming summer offensive on the eastern front. Thus, in his mind, Tunisia had to be kept as long as possible, with the minimal distraction of forces, to not interfere with the great plans against the Soviets.

Given these contradicting views and the Allied superiority on the field, it is easy to understand that the days of Army group Africa were counted.

Battles of Sidi Bou Zid and Kasserine

The plan was to gather the mobile and armored units of the two armies to strike against the American corps in central Tunisia and reach the crossroad and supply depots of Tebessa. There were contradicting views on subsequent objectives and certainly, the disregard that Rommel and Von Arnim had for each other, did not facilitate the operations.

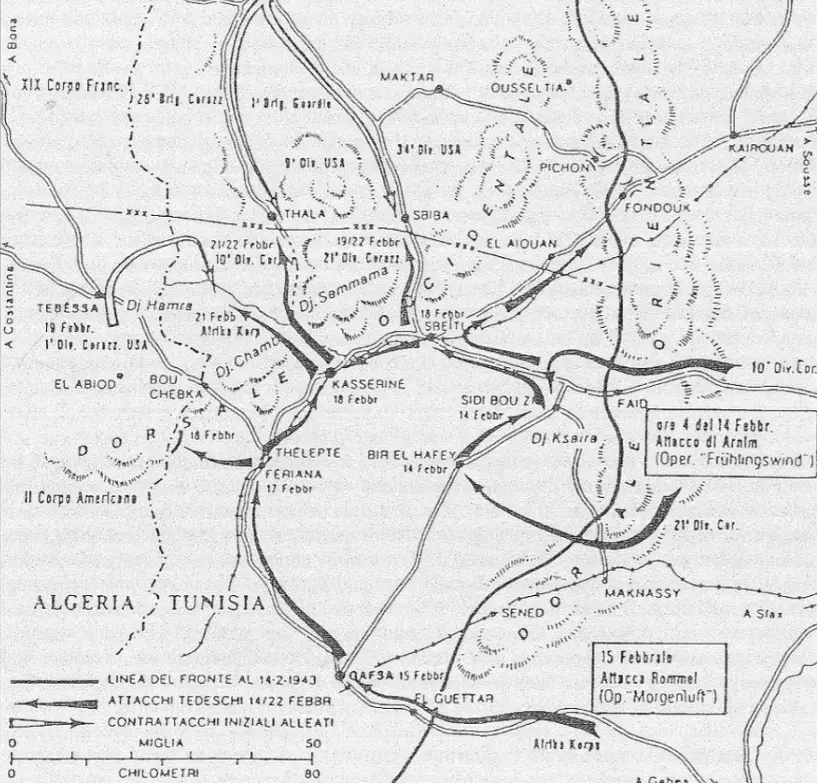

Figure 1Movements of the Axis forces during the operations at Sidi Bou Zid and Kasserine

On the 14th of February, the 10th and 21st Panzer divisions attacked the Americans at Sidi Bou Zid, defeating the defending forces and the subsequent counterattack. The success in this sector was not exploited any further, thus the panzers did not proceed further.

Some days later, Rommel himself attacked the American forces at the Kasserine Pass. He had with him elements of the 15th Panzer Division and the Centauro. It is perhaps largely unknown that the Italians participated in the clash, with Bersaglieri units on the left flank and tanks on the center together with the German panzers. The Axis forces broke through the pass but again the success was not exploited in the following days.

Von Arnim’s refusal to move south elements of the 10th Panzer Division coupled with the arrival of new allied forces in the area, prevented Rommel from exploiting the breakthrough. The Axis forces withdrew to their initial positions and moved south to face the imminent assault of the British 8th Army.

The Battle of Medenine

On the 23rd of February, Rommel assumed command of the Army Group Africa and Messe of the 1st Italian Army. The two commanders were aware that the forces deployed on the Mareth line would have been unable to resist a prolonged and brutal assault from the 8th Army. With the objective of buying time, Rommel conceived the idea of attacking Montgomery’s forces in their organizational phase at the road junction of Medenine, right in front of the Mareth line.

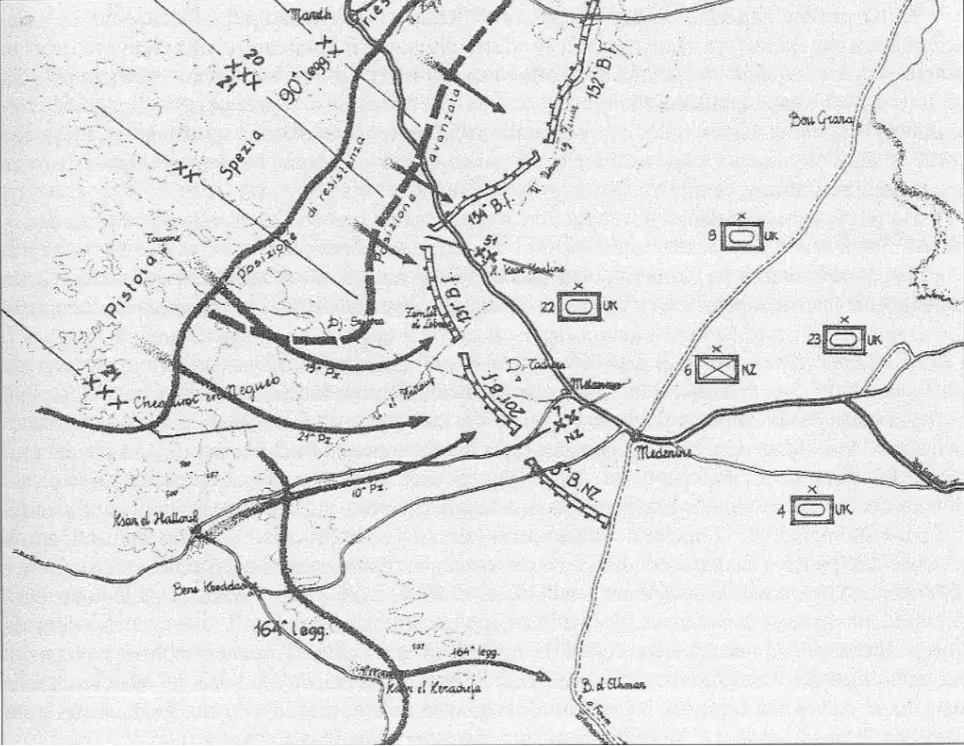

Rommel proposed a pincer movement from the coastal area and the southern sector of the Mareth defenses. Messe and other commanders opposed this initial draft, eliminating the northern pincer in favor of a concentrated thrust from the south and the center. Rommel finally approved this new version and thus Operation Capri began to take shape.

Alerted by decryptions of Enigma messages, Montgomery was made well aware of the Axis plans and thus prepared his formations accordingly to defeat the incoming attackers.

Elements of the three Panzer divisions began their March in the early hours of the 6th of March, while the Spezia and 90° divisions launched a supporting attack in the center.

The Axis movements at Medenine

The attack soon crushed against the barrage of British anti-tank guns, awaiting the Axis tanks. By late afternoon, Operation Capri was called off, after the loss of 50 out of 142 tanks and 635 casualties. This was the last major Axis offensive on African soil and the last battle for Rommel in this theatre. He left Tunisia a few days later, passing the command of the Army group onto Von Arnim.

The forces of General Messe were now awaiting the upcoming onslaught of Montgomery’s 8th Army.

Sources

Ford, K. (2012) The Mareth line 1943, Osprey publishing

Montanari, M. (1989). Le operazioni in Africa settentrionale, Volume IV: Enfidaville (Parte prima). Roma: Ufficio storico dello stato maggiore dell’esercito.

Jowett, P. (2019). L’esercito italiano nella seconda guerra mondiale. LEG edizioni.