Context

November 1941 can be considered as the most terrible period for axis convoys directed to Libya. During that month, only 30% of supplies went through, hammered by a renewed Allied offensive carried by bombers, submarines and surface ships. The most emblematic episode of this period is perhaps the loss of the “Duisburg” convoy, comprising of two tankers and five merchant ships. The loss came ten days before the start of the Commonwealth offensive in North Africa that came under the name of “Operation Crusader”. Surely the supplies carried by the convoy would have been extremely useful to Rommel in facing his advancing enemies.

Back on the 21st of October, Force K started to operate from Malta, this force consisted of the light cruisers HMS Penelope and HMS Aurora, together with the destroyers HMS Lively and HMS Lance. Such units had the objective of threatening the axis supplies routes, in preparation for the upcoming Operation Crusader. The Regia Marina (Italian Navy) became immediately aware of the Force K presence in Malta and requested the intervention of the Regia Aeronautica (Italian Air Force) to strike the enemy ships in the Grand Harbour. However, the Italians could not rely on sufficient numbers of dive bombers, so the standard level bombing proved ineffective. The presence of Force K led to a sharp decrease in the traffic between Italy and Libya, thus the Regia Marinna began to organize a large convoy protected by a powerful escort.

The “Duisburg” convoy

It was finally decided to send a convoy of 2 oil tankers and 5 merchant ships which carried 26.000 t of various supplies, 10.666 fuel barrels and 470 vehicles. Six destroyers formed the close escort while the heavy cruisers Trento, Trieste and four destroyers formed the indirect escort. The navy high command decided that the convoy had to follow the route east of Malta, this was a longer route than that the west one (passing off the Tunisian coast) but granted some advantages:

– It was out of range of Malta-based aircraft

– It granted room for manoeuvre in case of sighting the enemy

– It was less threatened by mines

– It passed in areas with the less intense submarine presence

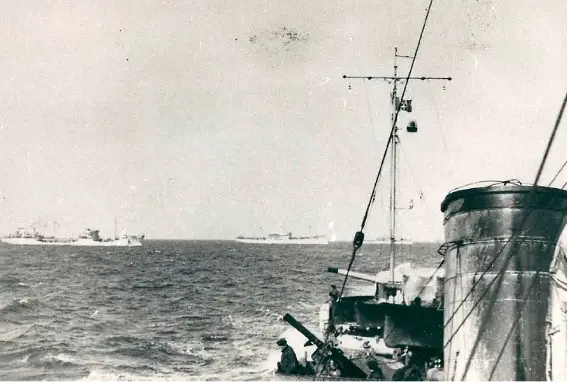

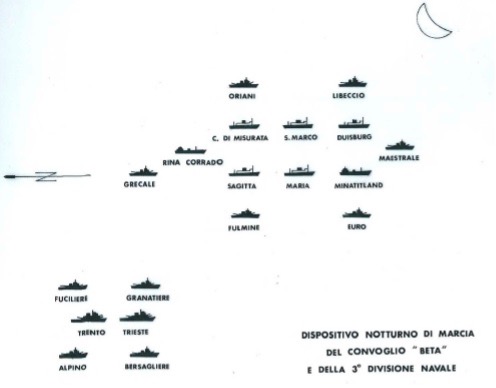

The convoy began its navigation in the morning of the 7th November, the lead ship was the German merchant ship Duisburg (thus identifying the whole convoy), accompanied by the oil tankers Minatitland and Conte di Misurata, plus the merchant ships San Marco, Maria, Sagitta and Rina Corrado. The destroyers Oriani, libeccio, Fulmine, Euro, Maestrale and Grecale formed the close escorts, followed at distance by the cruisers Trento, Trieste (3rd cruiser division) and the destroyers Fuciliere, Granatiere, Alpino and Bersagliere. Also, the air escort of the convoy was quite impressive, with a total of 10 ASW seaplanes CANT Z.506 and 66 fighters exchanging turns over the convoy. However, in the afternoon of the 8th, a Malta-bases recognizance aircraft sighted the convoy and one hour after the sighting, the Force K was already leaving the Grand Harbour under the cover of darkness, making it impossible for the Italians to know where the British ships were. Decryptions of enemy communications also provided the British with the detailed information on the route followed by the convoy.

The heavy cruiser Trieste

The ships of the Duisburg convoy

The disposition of the Duisburg convoy

The clash

During the navigation at night, Admiral Bruno Brivonesi, commanding the indirect escort, ordered his ships to navigate in circles around the convoy, given the low speed of the latter (max 9 knots). In the meantime, Force K was approaching the Duisburg convoy and, at around 00:40, sighted the Italian ship, at a distance of 11 km. The British warships got closer and then proceeded in a column on a southeast course to unleash a full broadside on the enemy convoy. After 17 minutes from the sighting, the cruisers Aurora and Penelope opened fire, helped by radar in their fire direction, soon followed by the destroyers Lively and Lance. The Italian destroyers Fulmine and Grecale were the first to be hit and desperately tried to react by firing their 120mm guns but with no success. The Grecale got immobilized while the Fulmine sunk after an internal explosion caused by the damage received. Then, Force K concentrated on the merchant ships, hitting them one after the other. In the meantime, the indirect escort was 3.5 nautical miles north of the convoy and saw the enemy firing right in front of them, at around 9-10 km. Admiral Brivonesi ordered a new course to the southwest, to clear the firing arc and to unleash a full broadside, however, they scored no hits. The Italians lacked radar and optics to conduct effective night actions, and this certainly limited the effectiveness of the 3rd division’s reaction. However, the Italian escort ships kept firing against the obscured enemy ships, which kept pounding the merchant ships and the escorting destroyers. Force K manoeuvred in a way to cut the way to the convoy and then get back northwards on the left flank of the merchant ships, which at this point were all sinking or on fire. The 3rd cruiser division, fired for around 20 minutes against force K, consuming 207 of the 203mm shells and a similar number for the lower calibres. The destroyers of the close escort manoeuvred to the southeast, laying smoke screens but none aboard the Italian ships clearly understood the situation, some also believed they were attacked by aircraft. At around 1:30 AM, Admiral Brivonesi ordered his ships to revert their course to the northwest, away from the convoy. He rightly assessed that the enemy was trying to circumvent the convoy on the other side and then sail west towards Malta. By changing course he would have had a chance to cut the way home to Force K. In the same moments, wrong information from Supermarina (the Navy high command) reached Brivonesi, it read that there could have been attacks by submarines and torpedo bombers launched from an enemy aircraft carrier. This led the Admiral to not wait for the ambush and proceed north, reaching the area covered by Italian land-based fighters. Consequently, Force K did not find any enemy ships on their way back and made it back to Malta.

The surviving destroyers of the close escort remained in the area, rescuing the survivors from the cold water, the destroyer Maestrale picked up around 400 people, threatening its ability to stay afloat. The next morning, the British submarine HMS Upholder spotted some Italian destroyers rescuing the survivors and launched its torpedoes against the targets. At around 6:40 AM, one hit the destroyer Libeccio and the explosion almost wiped out the entire stern section. The destroyer Euro tried to tow the damaged Libeccio, but it was all in vain. The ship was too badly hit and sunk around 11:18 AM.

The Libeccio sinking

Considerations

The loss of the Duisburg convoy was a terrible hit for the Regia Marina, which occurred in a delicate period for the war in the Mediterranean theatre. The inability to effectively fight at night hindered the Italian response to the attack and the whole month of November registered high losses and major interruptions in the traffic towards Libya. Admiral Brivonesi was accused of misconduct and removed from command, later even subject to a military trial that eventually declared him “not guilty”. The British scored a major success, being able to intercept an enemy formation at night thanks to precious intelligence gathered by Ultra and to dominate the engagement thanks to radar, night optics and the element of surprise.

Sources

Giorgernini, G. (2001). La Guerra Italiana sul mare, La marina tra vittoria e sconfitta 1940-1943.

Mattesini, F. (2015). Il disastro del convoglio “Duisburg”.

O’Hara, V. (2000). La distruzione del convoglio “Duisburg”. Tratto da Regiamarina.net: http://www.regiamarina.net/detail_text.asp?nid=67&lid=2