THE PREMISES

When the war started, Italy could just get bombed by RAF aircrafts coming directly from Britain, but those targeted only the factories in the Milan Area and didn’t do any major damage.

The first bombardment occurred just 5 days after the declaration of war against Britain, on the night of the 15-16th of June, and targeted the Caproni plant, causing little to no damage.

Several other raids were carried out in August by the RAF, dropping bombs along with propaganda leaflets; these bombs were intended, again, for the Caproni plant, but ended up in some houses and buildings along the streets, killing 15 and wounding 44 people.

All throughout august the RAF continued with those bombardments, always targeting the Caproni factory or the Innocenti ones near Linate Airport. The last bombardment of 1940 was carried out in December, when 3 planes tried to reach the Pirelli plant, failing and instead causing damage to a few houses, killing 8 people.

2 YEARS OF PEACE, OR SO IT SEEMED

The Italian peninsula was not subjected to aerial attacks for another 2 years, when the industrial cities were targeted again. RAF bomber command, now under the command of Sir Arthur Harris, intended to use the Area bombing tactic, which proved to be successful against the Germans, on the most important industrial cities of Italy: Milan, Turin and Genoa.

These 3 cities were the neuralgic center of industrial power, and so were very important to the fascist regime. The englishmen knew that by targeting those cities, the approval rating of the fascist regime would have collapsed since they knew they couldn’t defend them. And so those bombardments started.

The most targeted was Turin, with 7 raids, Genoa comes close with 6, and Milan, strangely, was the one hit less by the raids, at least in this phase. On October 24 1942, the RAF arrived over Milan with 73 Lancasters, dropping 135 tons of bombs (of which 30,000 incendiaries) over the city. In this attack, over 400 buildings where hit, most notably the San Vittore jail, the headquarters of Hoepli (italian publishing store), 2 train stations and the Cimitero Monumentale (Monumental Graveyard). 171 people were killed and 300 wounded. In contrast, just 4 Lancasters were lost, of which only one from AA fire.

(note: Italy at that point didn’t have a functioning radar system, it was still using the aerophones, a kind of instrument capable of intercepting the sound of incoming aircrafts, determining the direction from which they were coming from.)

In the aftermath, bomber command determined that the incendiaries were to no use in Italy, since the cities had wider streets and the buildings used less wood compared to the German ones.

The following day, another 71 planes were dispatched over the city, but just 39 reached Milan, with 6 lost and the other dropping their bombs randomly over the near villages. Again, little to no damage was done to the buildings and the factories. What was hurt the most was the morale, with thousands of civilians fleeing the city for the countryside.

To better aim, Harris decided to use the Duomo as the aiming point, and this caused criticism among the ranks and the members of Parliament.

In the following months, German Flak was added along the Italian AA, hoping to improve air defense, but, after some time, it was determined that it didn’t change significantly.

A series of new bombardments started on the night of 14/15 February 1943, when 110 tons of explosive bombs and 166 tons of incendiaries were dropped by 142 Lancasters. This time the damage done was serious, with several factories, like Alfa Romeo, Caproni and Isotta-Fraschini targeted and hit by the bombs. Also hit were the Milano Centrale railway station and some train deposits. Some residential areas were damaged, with 200+ houses destroyed, almost 600 heavily damaged and 3000+ slightly damaged.

Even the Corriere della Sera journal headquarters suffered damage. The bombardment also hit some historical buildings, like the Royal Palace, the Basilica of San Lorenzo and the Teatro Lirico. To extinguish the fire, firefighters from all over the region had to be called. In total 133 people were killed, 400+ wounded and over 10.000 were now homeless. The only loss for the RAF was a Lancaster.

AFTER MUSSOLINI’S FALL

After this attack, Milan skies were free for another 6 months, then, in August 1943 with the fall of Mussolini, the Allied command decided to resume the bombardments as to persuade Badoglio’s Government to surrender: on the night of the 7th of August, 197 bombers took off from England to fly and bomb Milan, Turin and Genoa.

Milan was attacked by 72 aircrafts, with only 2 shot down by AA, and they dropped 201 tons of bombs, mostly incendiaries. These bombs set the center ablaze, destroying lots of buildings and killing nearly 200 people. In this attack, only the Pirelli factory was damaged. The historical buildings had the worst, with the Sforza Castle suffering heavy damage along with the Natural History Museum and the Pinacoteca di Brera. However, the heaviest raid had yet to come.

THE HEAVIEST OF RAIDS

On the night of the 12th of August, the RAF launched it’s heaviest bombardment against an Italian city. The raid, composing of 504 aircrafts, mostly Lancasters and Halifaxes, took off from England inbound to Milan, where 478 of them dropped 1252 tons of bombs, including almost 250 blockbusters.

This raid caused massive fires but, thankfully, there was no firestorm. As for the previous raids, the Sforza Castle was damaged, the city hall and the Church of Santa Maria delle Grazie were partially destroyed, while the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II suffered heavy damage. Various sources state that the death toll for this raid goes up to 700, but nothing is certain. In this raid, the RAF lost only 3 bombers.

2 days go by and another raid is carried out by Bomber command: 134 Lancasters dropped 415 tons of bombs. Several factories were again hit, the Sforza Castle and the Royal Palace were damaged again. The few remaining citizens helped the firefighters but their efforts were vane due to the destruction of the aqueduct pipes.

The Galleria Vittorio Emanuele after the Bombardment of the 13th of August

THE LAST ONE AND THE GORLA TRAGEDY

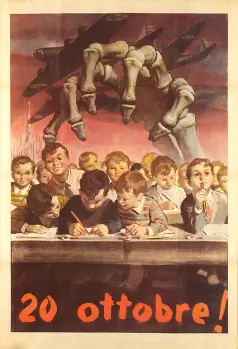

After this raid, the city saw clear skies until 1944, when the USAAF started bombing again. It was in this instance that the “Gorla tragedy” happened: on the 20th of October 1944, 36 B-24 of the USAAF went off-course due to a navigation error, and ended up releasing their bombs over the suburbs of Gorla and Precotto. The death toll rose to 614 civilians, of which 200+ where children, teachers and personnel of the “Francesco Crispi” elementary school, that received a direct hit while the students and personnel were trying to reach the air raid shelters; there were only 2 survivors. After this, no more bombing raids were ordered over Milan by the Allies.

A poster about the Gorla Tragedy

ROME GETS BOMBED

Another city hit by allied bombardments, although not as much, was Rome. The Italian capital didn’t suffer as much as Milan thanks to the Pope who, after the first bombardment on the 16th of may 1943, wrote directly to Roosevelt asking him that “Rome be spared as far as possible further pain and devastation, and their many treasured shrines… from irreparable ruin”.

Roosevelt answer soon followed on June 16th: “Attacks against Italy are limited, to the extent humanly possible, to military objectives. We have not and will not make warfare on civilians or against non military objectives. In the event it should be found necessary for Allied planes to operate over Rome, our aviators are thoroughly informed as to the location of the Vatican and have been specifically instructed to prevent bombs from falling within Vatican City”.

This way, the Pope hoped to at least spare Rome from the destruction caused by the bombardments, but he was wrong.

Not even a month passed by that Rome was bombarded again during operation Crosspoint: 521 planes attacked the city and caused between 1600 and 3200 victims. It was after this raid that the Pope decided to travel outside the Vatican walls to the “Basilica of San Lorenzo fuori le mura” and distributed over 2 million Lire to the crowds. Another raid followed at 11am, when 150 B-17 attacked the freight yard at San Lorenzo, then the “Scalo del Littorio” and lastly Ciampino Airport.

Raids over Rome continued until March 18 1944, when the 12th USAAF caused 100 casualties.

The Church of San Lorenzo after the bombing

Cover of the “Tribuna illustrata” depicting the episode

CONCLUSION

Why were Italian cities not so well defended during world war 2? The night fighters weren’t that powerful, given that the Italians didn’t have any radar with which detect the enemy. Italian fighter pilots also weren’t used to flying in the night using only the instruments, in fact they flew only with the moon light, when they were sure that they could spot the enemy.

Another factor was that the absence of radar alarms meant that they had to scramble only when the enemy was already over their field or the objective and those who could arrive in time weren’t that successful either, because enemy aircrafts were flying at high altitudes, meaning that, for the performances of that time, Italian aircrafts couldn’t attack them in time.

As for AA guns, the Italians had a large variety of assets, but those were not as effective as those of the other nations, nor were they produced in enough numbers to be effective. Indro Montanelli, a famous Italian writer, about this matter said: “there were more AA guns in London alone than in all of Italy”. This sentence alone describes how disorganized was the Italian Army regarding it’s weapons.