The life of Rodolfo Graziani began near Rome in Filettino, on 11 August 1882. The beginnings of his military career implied a bright future. The six-foot-tall Graziani rose through the ranks quickly, becoming Italy’s youngest Colonel. After his First World War service, his star in the Regio Esercito continued to rise, so to speak. An ardent fascist, Mussolini’s ascension to power played strongly to his benefit, delivering him to his first major command. In 1930, he won renown and notoriety for his command of the Italian forces in Libya. By the employment of tanks, aircraft, and brutal repressive measures, Graziani brought a decade-long war in Libya to a close.

Graziani in 1942.

By the declaration of the Second World War, the Regio Esercito held Graziani in high regard. This acclaim would quickly fall after Graziani’s failure in the invasion of Egypt. In the end, Graziani’s loyalty returned him to high command, and he offered the final Italian surrender on 01 May 1945.

“Pacifier” and “Butcher”

Rodolfo Graziani’s early military career first took him to Libya in the Italo-Turkish War. Later, he arrived at the largely-static Alpine Front of the First World War. He suffered two wounds in battle with Austrian forces during his time as a brigade commander. While he did not attain divisional command during the war, he achieved corps command during his tenure in Libya (1921-1934). As Vice-Governor of Libya from 1930 to 1934, he crushed the Senussi Rebellion. Utilizing auxiliary troops from the colonies augmented by Italian air and mechanized forces, he achieved significant battlefield success. In Italy, he grew famous as the Pacificatore Della Libia – Pacifier of Libya. However, his actions against the civilian population of Cyrenaica earned him another title among Arabs; The Butcher of Fezzan.

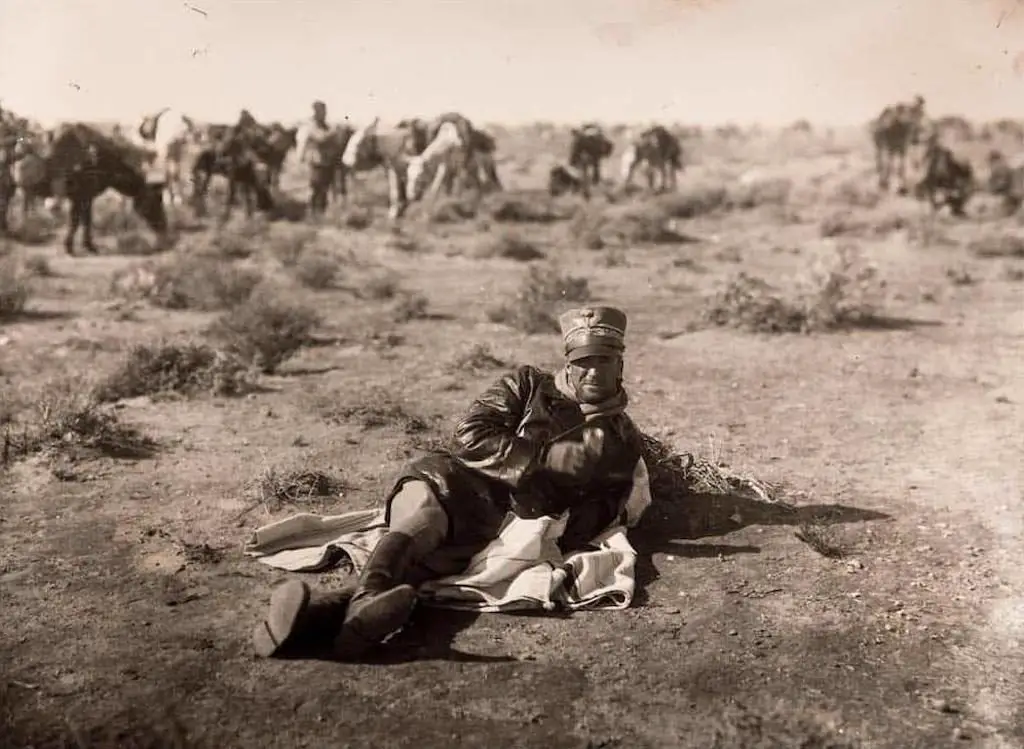

General Rodolfo Graziani, “The Butcher of Fezzan” drinking a beverage (possibly coffee) while relaxing on the desert floor of Italian Cyrenaica, Libya. Photograph taken circa 1931.

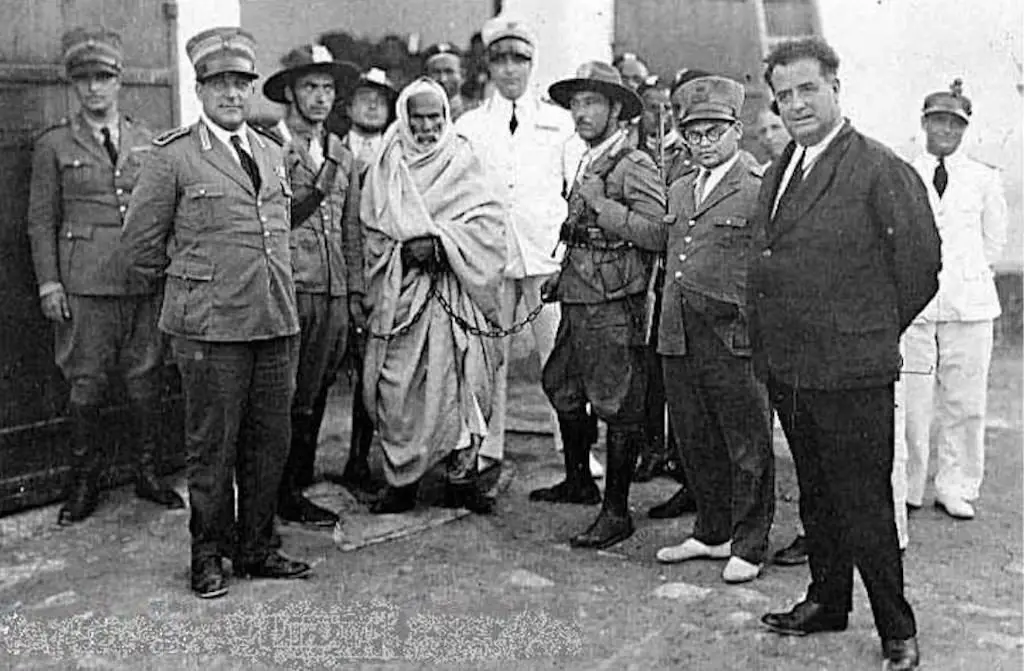

Under his orders, many civilians found themselves interned in camps, separated from the rebel population. The camps lacked proper sanitation and sufficient food, resulting in many deaths among the civilian population. Additionally, he displaced as many as 100,000 Bedouin from their settlements to free them for Italian settlers. By the end of Graziani’s time in North Africa, most of the population had died or been displaced. Rome declared the pacification complete after the capture of Omar Mukhtar, the principal leader of the rebellion. The resistance against Italian colonization ended with the execution of Mukhtar on 16 September 1931 in front of 20,000 Libyans.

Omar Mokhtar arrested and in chains prior to his execution.

Promotion and Transfer

In 1934, Rodolfo Graziani returned to Italy. Mussolini awarded him with the coveted command of the Udine Army Corps. And, shortly afterward, Graziani was promoted to a Generale Designato d’Armata, the highest rank in peacetime.

With the end of Graziani’s assignment there, he was soon transferred to command the Southern wing of the 1935-1936 invasion of Ethiopia.

Reign in East Africa

As Ethiopia divided the Italian colonies of Somaliland and Eritrea from each other, it had long been a target of Italian foreign policy. Additionally, the desire to avenge the humiliation of the 1895 Battle of Adwa was near universal in Italy. Eventually, the situation came to a head in 1935, and preparations were made for a two-pronged invasion in 1936. The main effort occurred in the north, under Marshal Pietro Badoglio. Graziani’s forces as the Governor of Italian Somaliland were only to provide a diversionary, defensive effort. Given the wide frontline and their small numbers, they were seemingly not capable of more.

Graziani in Addis Ababa.

However, this role did not satisfy Graziani. He took the initiative in buying civilian trucks and vehicles from abroad and greatly increased the mobility of his forces. In doing so, his 60,000 men were able to undertake effective offensive action across the vast Ogden Desert. Despite the lesser importance of his command, the success of the campaign saw a further promotion for Graziani. First, to Marshal of Italy, and then Viceroy of Italian East Africa. His experience in perhaps the first instance of modern mobile, combined arms warfare helped to craft the Italian maneuver doctrine.

His viceroyship of Ethiopia is aptly described by an infamous quote:

The Duce will have Ethiopia, with or without the Ethiopians.

His style of leadership carried over from time spent in Libya. However, his hostility and suspicion towards the natives intensified as rebels made several attempts on his life.

Yekatit 12 (Addis Ababa Massacre)

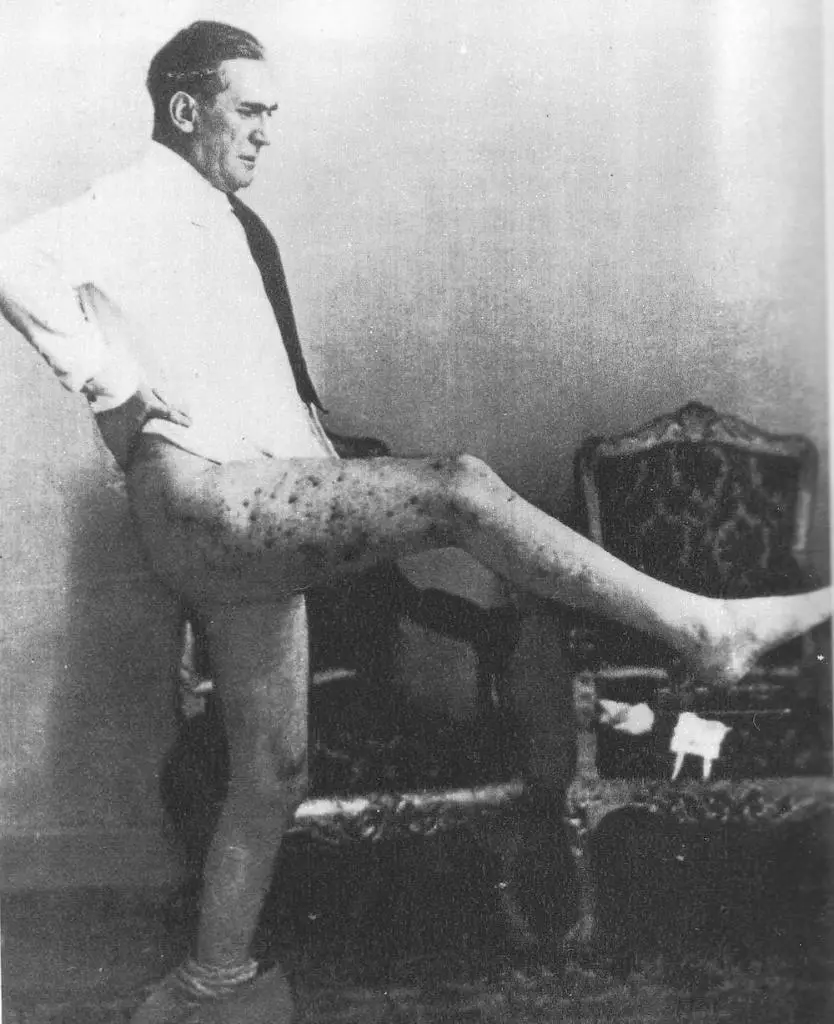

His harshest reprisal, known as Yekatit 12, or the Addis Ababa Massacre. It involved the indiscriminate killing of thousands of Ethiopians. On 19 February 1937, Rodolfo Graziani attended a ceremony inside the Genete Leul Palace (known also as the Little Gebbi). Two Eritreans, Abraham Debotch and Mogus Asghedom, threw 10 grenades at the attendees. Seven people died and 50 were injured, including Viceroy Graziani. Approximately 350 grenade fragments punctured his body. From the hospital, Graziani ordered a quick and violent retaliation. In three days, Italian forces murdered over 30,000 Ethiopians in reprisal.

Viceroy Rodolfo Graziani showing his leg injuries caused by grenade fragments.

His methods in Ethiopia were not as effective as they were in Libya. Consequently, he left Ethiopia on 10 January 1938 and returned to Italy.

In 1939, on the cusp of the Second World War, he ascended to the post of Commander in Chief of the Regio Esercito. It was here that Rodolfo Graziani made his most famous mark on the history books.

A Preview of Failure in the Invasion of France

As Italy joined the conflict, Graziani held strategic command of an army that was ill-prepared for war. The ill-planned, ill-executed invasion of France was the first example of this unpreparedness. Sorely under-equipped troops marched into the harsh Alpine terrain and strong fortifications, with predictable results. They suffered relatively heavy losses and gained little ground, despite apparently light French resistance. However, French surrender precluded any strategic consequences for this failure.

During Graziani’s command in Libya, however, disaster would occur.

Operation Compass and Graziani’s Fall From Grace

Graziani held a deep, somewhat well-founded pessimism in regards to Italy’s odds in a war with Britain. He accused Badoglio of having sent him to the front without the necessary reinforcements, especially trucks, tanks, and modern artillery, for the invasion and conquest of Egypt.

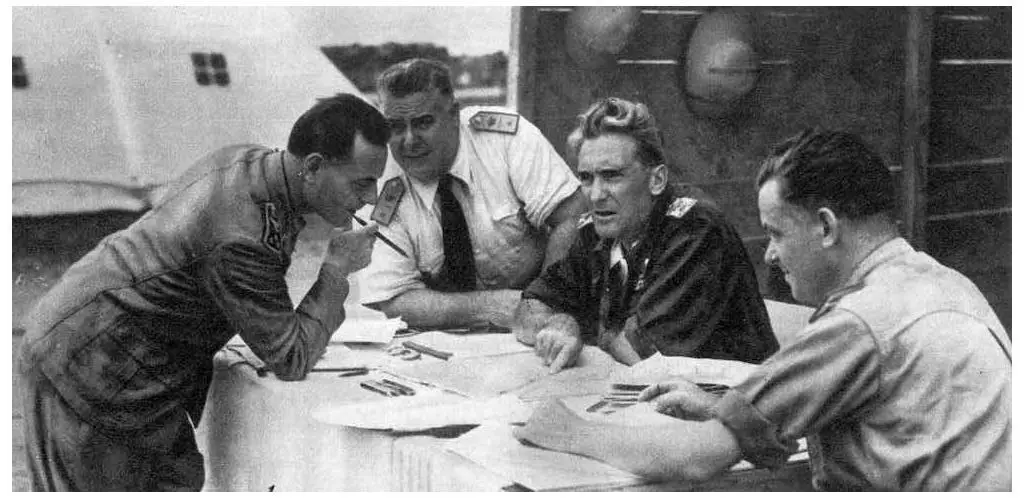

Graziani holds a staff meeting in North Africa.

At every turn, he delayed the invasion, until Mussolini’s insistence forced him into action. The initial 80,000 men of the 10th Army possessed an advantage in manpower, as compared to the 36,000 men of the British Western Desert Force. Despite the apparent disparity, many of these units consisted of ill-trained, ill-equipped colonial troops and Blackshirt fascist militia. While the 10th Army did possess more heavy weaponry than the WDF, it lay thinly dispersed. Logistical issues and motor transport were severely inadequate, handicapping their ability to fight and maneuver. The lofty goal of reaching the Suez Canal quickly fell to a modest, 65km penetration over the border.

With the initiative ceded, the British were free to reinforce their troops in Egypt. By now equipped lavishly with motor transport and with superior tanks, they conducted Operation Compass. The plan initially called for a raid on the overstretched Italian forces, with the potential to escalate if successful. However, after discovering the weakness of the 10th Army, it grew into a full-blown offensive. The Italian forces suffered a rout, and a catastrophic defeat ensued; 138,000 men killed or captured, and all of Cyrenaica lost. Graziani’s resignation as quickly accepted, and he briefly faced the threat of court-martial.

It took the arrival of General Erwin Rommel with a Panzer and Motorized Infantry Division as well as the Italian Ariete and Trento Divisions to reverse the losses.

Fault for the Disaster?

A prevailing narrative places blame for the defeat on the Italian troops themselves; either incompetence, poor morale, or another critical tactical deficiency. However, a strong argument can be made that Graziani still bears responsibility for the defeat. His decisions violated the experience of the Spanish Civil War and the Italian doctrine of War of Rapid Decision.

Rodolfo Graziani in 1943.

The Battle of Guadalajara demonstrated the danger of utilizing militia and light troops in a conventional battle. The later Battle of Santander demonstrated that fewer, better equipped and trained troops would achieve much better results. The War of Rapid Decision dictated, in theory, that one should employ mechanized forces and artillery offensively to gain decisive results. If Graziani’s pessimism led him to seek safety in mass or if he simply forgot these lessons, no one can know.

Minister of National Defense for the Italian Social Republic

Despite the disaster, Graziani’s loyalty to fascism returned him to Il Duce’s good graces. Many of his marshals sided with the King, after the deposition of Mussolini and armistice with the Allies. Graziani, however, remained alongside Mussolini and Germany.

A woman salutes Graziani.

From 1943 to 1945, Graziani served as the Minister of National Defense of the Repubblica Sociale Italiana (RSI), the German puppet state in northern Italy. He helped plan the Battle of Garfagnana, a divisional level attack meant to throw Allied forces off balance. It was a victorious battle for the Italo-German forces but offered more propaganda significance than military.

Graziani with Junio Valerio Borghese on his left in Milano, Italy.

Shortly afterward on 01 May 1945, Rodolfo Graziani offered the final surrender of Axis forces in Italy.

Post War and Death

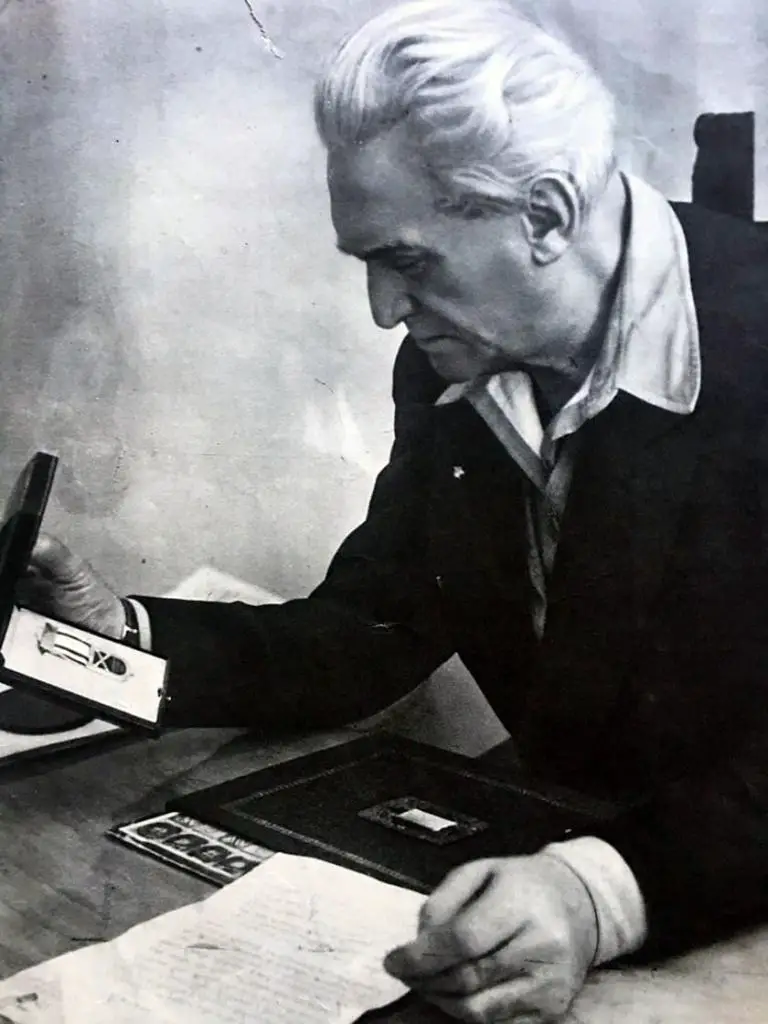

Graziani is seen here in his later years as he looks at a war medal.

After the war, Ethiopia pushed to have Graziani charged with war crimes for his actions in their country. However, this was largely blocked by British officials and came to nothing. His opposition to the Italian Republic and service to Mussolini’s Repubblica Sociale Italiana did result in charges of treason. Despite a conviction, he only served a small portion of his 19-year sentence. Ultimately, Rodolfo Graziani remained a vocal, unrepentant fascist until his death on 11 January 1955 in Rome, Italy at the age of 72.

Link of interest: Graziani’s Service Record.