As with the Italian Air Force and Navy, writers had put much emphasis on seemingly significant weaknesses in the Italian Army’s organization and equipment when Italy entered the war in 1940. However, as with the Navy and Air Force, when putting these weaknesses in a relative context, they are less noticeable. The Italian Army was immense, particularly when comparing it with what it first was to come up against, and as such, had great potential for adjustment and streamlining towards specific missions.

General Pietro Badoglio opposed Italy’s entry into the war.

Comando Supremo’s leadership in the spring of 1940 decided that in the case of war, Italy should take an active stance in the air and on the sea but act passively on the ground. Germany had not yet invaded the Low Countries and France with the resulting disastrous result for the Allies, so this was a rather prudent choice to make. The reality at the time was an undefeated France supported by the British Empire, both potential enemies having several common borders with Italy.

Italy’s North African colony, Libya, was hemmed in by a British-dominated Egypt on one side and the French colonies of Tunis and Algeria on the other. Its Eastern colonies, Somalia, Eritrea, and Ethiopia, were, in the case of war, threatened by British forces in British Eritrea, Somalia, and Kenya. Just as the First World War, British Dominion forces could mobilize in Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and India for this purpose.

Supply and Support Issues

With the British in complete control of the Suez Canal and dominating the seas outside the Mediterranean, Italy had a problem that needed quick resolution if it entered the war – the continued supply and support of their forces in Africa Orientale Italiana (AOI). Mainland forces could defend Italy’s shared border with France, and there was only a short, direct route from Italy to its Libyan colony. AOI, however, was surrounded by potential enemy forces and very hard to support as long as the British controlled the Suez Canal.

The Italian Air Force developed a long-range transport capacity. By flying across British-held territory (Egypt and Sudan), preferably during night-time, they could reach the Italian bases in the AOI. However, this capability did not meet the need to supply the garrisons, which numbered several hundred thousand men, and the vast quantities of equipment in need of constant resupply and maintenance. There was also an Italian naval contingent in the Red Sea. To make the supply of these colonies dependent on overseas transport would be nearly impossible with the Royal Navy controlling both Gibraltar, the Atlantic, and the Indian Oceans, with a multitude of naval and air bases along the long route around the Southern point of Africa.

Cruiser Bartolomeo Colleoni in the Suez Canal.

Italy’s priority, therefore, ought to be the conquest of Egypt by a concentrated assault with all available forces to open up the transport route through the Suez Canal and the Red Sea. However, it did not fit into a passive army strategy. Therefore, no real maritime transport plans had been agreed upon by the Navy and the Army for an eventual rapid build-up of the Army forces in Libya (Bragadin).

Albania and Dodecanese

In addition to these hotspots, there were Albania and the Dodecanese. As a follow-up to an Italian influx into Albanian economics through the twenties and thirties, Albania was invaded by Italian forces in April 1939. After a short struggle, Albania was forced to join the Italian Empire. King Vittorio Emanuele III was offered its throne on April 12th, 1939. With that, Italy had achieved a crucial strategic improvement in that it now controlled both sides of the approach to the Adriatic Sea, the Otranto Strait. They were denied this when they were ejected from Albania in 1920. But it was also to become a liability that sucked up more troops and resources.

Binary Divisional System

The three most referred to alleged inadequacies of the Italian Army in 1940 has been its small-sized divisions, lack of proper armor, and old-fashioned artillery. If the country’s policy followed the general directive of its Superior Commander, General Pietro Badoglio, the two first complaints could be rectified by simply concentrating the overly large Army where it was needed. A defensive attitude in Western Italy could yield several extra divisions to overwhelm the British defenses of Egypt and the Suez Canal.

As a whole, statements on the Italian small-size divisions are somewhat superficial. Benito Mussolini had introduced the binary infantry division system before the war, i.e., two regular regiments per division as opposed to the standard complement of three. If we compare with the German infantry divisions, they had this as a norm. In contrast, the mountain (gebirgsjäger) divisions had two regiments each. The British Army at the time was much less standardized with a hodge-podge of part-regiments – battalions from various regiments in brigades rather than regiments. The number of brigades in a division, if so organized, often numbered less than three.

Related: Italian Military of 1940: Facilitator or Victim of Mussolini’s Failed Strategy?

On the other hand, British brigades could consist of more battalions than the standard three of a normal regiment. As important as the actual number of regiments in a division would be the composition of the regiment itself, the number of battalions, and support elements therein. Some Italian regiments had more than the usual amount of three battalions. Added to this was the main support element, the artillery regiment, but also divisional units like independent artillery, mortar or machine gun companies, batteries, and engineer units.

In the end, the most crucial factor should be the total firepower of a given combination of battalions, regiments, or divisions. A three-divisional Italian army corps could, as an example, equalize a two-divisional normal army corps. While, all other factors being equal, the size of independent army corps units would be larger. This point is just to illustrate that the binary divisional system wasn’t necessarily a drawback, but more a question of using more of them or adding battalions or regiments as needed. More binary divisions also created an opening for faster expansion in that the divisional core was already in place.

Industrial Capacity

Armor and heavy artillery are costly and resource-demanding, and here was the most significant Italian drawback, its limited industrial capacity. The Army could not compensate for this within a short time-frame. They had to use what they had most effectively and hope for a quick end to an eventual war.

Armor

As for armor, again, we have to look at conditions in the summer of 1940. The French had a large tank force with a robust influx of heavier types. But this was not that important if the Italians selected a defensive stance on their Western border while a German threat against France in the North had to be considered in the French defense plans.

The British Desert Force, however, was not much better equipped than the Italians until they received the Matilda tank in any numbers. With the M11/39 and M13/40 tanks, the Italian Army was otherwise on par with the enemy. The M13/40 had the largest-caliber gun in the desert at the time but was few in numbers. Italian tanks also had a distinct advantage over the British ones as they were powered by a V-8 diesel engine. These engines were less flammable than the British petrol engines and less fragile under storage conditions.

In the summer of 1940, the Italian M13/40 was still the most powerful tank in the desert.

As a drawback, fuel could not be drawn from the main petrol stores. When we look correctly into the story, the British tanks were no more reliable, mechanically, than the Italian ones. There is plenty of evidence on this, and the harsh desert conditions were just as taxing for all parties.

A concentration of Italian tank and infantry resources could undoubtedly carry the day in a summer 1940 scenario if adequately led, considering the light British forces of Egypt.

Artillery

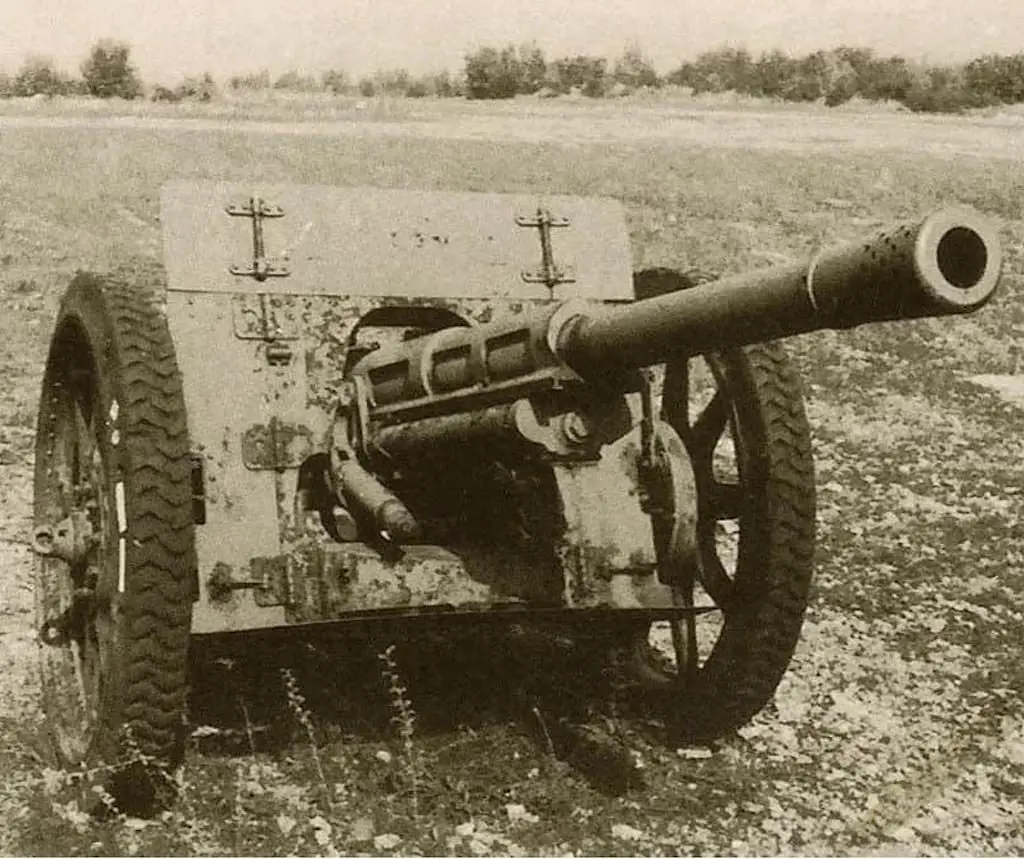

What is most criticized is undoubtedly the Italian artillery. It was supposedly for a large part horse-drawn, of pre-WW1 or WW1 vintage with only a small influx of more modern units.

A gun is a gun is a gun? Not exactly, but what was wrong with a WW1-vintage gun (cannon)? In principle very little, more or less all parties used them to a certain degree during the war. World record in this respect must be held by the French 75 mm Schneider gun that originated in 1898. Oh, yes, the modern ones would probably have rubber tires. That could be refurbished. Did they have a shorter range? Would it fire slower? Would it be less accurate? Would it get hot faster? Was its ammunition less effective? How had they been maintained? Much of Italy’s older artillery had been taken over from the former Austria-Hungarian Army after WW1, of Skoda manufacture, a highly respected cannon manufacturer. There also were new, indigenous Italian gun designs. However, the lacking industrial base before the war did not allow a complete change-over to these.

The Italians did not use horses for pulling guns in Africa, not in the desert, anyway, considering the inherent water problems. The Italians were pioneers in using motor transport in the desert. If not pulled by trucks, the guns were hoisted up on trucks for transport.

More important than the technical differences between a modern and an aged gun would be the training of the personnel. Could they handle and position their guns properly? Did crews cooperate efficiently? Did they know how to aim according to instructions? Were they led by professional officers who understood and could use the tables, their observation, and fire-control systems? Was the ammunition supply working? Were the batteries organized for close-in defense?

The Italian Army may have had a production and supply system problem. But the way Italian designers, engineers, officers, and soldiers are downgraded by the constant bickering on inferior products and mechanical break-downs does not necessarily reflect the quality of their products’ designs or the handling of them. The Italian private companies turned into war material manufacturers were winners of many sizeable international car and air races with domestically produced machines, but regular maintenance with a proper flow of spare parts was nevertheless required. What other nations could execute the multi-aircraft trans-Atlantic flights as did Italo Balbo and his men in the early thirties?

Cannone da 75/32 – a versatile, indigenous Italian design.

German Unilateral Actions

Hitler’s affection for Mussolini, after he approved of the Austrian Anschluss, cooled off somewhat when Mussolini decided to stay out of the war when Germany invaded Poland. He felt insulted by Hitler’s secrecy when subduing Czechoslovakia. His restrain in September 1939 was reinforced by the same attitude by Hitler not to inform in advance about his Polish adventure. To continue their budding love-hate relationship Hitler also had no intentions to tell the Italian dictator about his next moves, the invasion of Denmark and Norway, followed by the great assault in the West. Not uncalled for considering the need for secrecy involving any military operation.

Before Operation Gelb (yellow), the invasion of the Low Countries and France, Hitler played with the idea of asking Mussolini to contribute several divisions north of the Alps to give more punch to his final attack on France (Warlimont). The idea was dropped soon after May 20th, the same day the mouth of the River Somme was reached by the German panzer spearheads.

Events developed with such rapidity that there seemed to be no need for any external support. Hitler was the more perturbed when a note arriving from Mussolini on May 30th informed him that Italy was to enter the war on June 5th. Contrary to Mussolini’s expectations, Hitler thought it better to wait a few days. He was obviously of the opinion that the Italian entry into the war would only complicate matters (for him). In essence, it might hurt the final German push down mainland France, he said. How this could be was not explained, but Mussolini immediately asked for Italo-German staff talks, which Hitler responded to evasively.

In the meantime, there was an increasing concern within French government circles to approach Italy with offers of compensation to stay out of the war (Spears). The Dunkirk evacuation was in an early stage. While the British Expeditionary Force had orders to save itself, without being totally honest about it with their French allies (Weygand), there seemed to be little hope of saving the large French contingent that was more or less surrounded by the Germans North of the River Somme.

Italian entry into the war at this stage would undoubtedly be the death knell of France. To avoid this, some of the French leaders suggested offering Italy parts of the French North African colonies, partnership in the Suez Canal, as well as to “internationalize” Gibraltar and Malta. Paul Reynaud, the French Prime Minister, was also not totally against this. The discussions lingered for some days. Then the British, having tried to stop any such contacts with the Italians, categorically denied any offers concerning British territories of influence, primarily Gibraltar and Malta. The French could offer whatever they liked of their own property as long as it was understood that this involved no part of anything British. In time Churchill was able to bring Reynaud over on his side to the extent that no contact was taken with Italy in this respect. This was on May 31st.

Having no knowledge of these proceedings (Spears), Mussolini postponed the declarations of war to France and Great Britain for five days. When Italy finally entered the war, they based it on a parallel strategy with Germany that was to become much the pattern of the future. The Italian Army’s initial passive role, as instructed by General Badoglio, was quickly forgotten. The rest is history.