On the eve of the fall of the Italian empire in East Africa, the small trimotor Caproni Ca.148 I-ETIO attempted the impossible: to reach Italy. The mission was a long shot and required a strong dose of courage and good fortune. Defying all odds, the mission concluded successfully. The odyssey lasted four months.

Evacuation Order for Italian East Africa

Between June 1940 to October 1941, the Regia Aeronautica utilized a few transport aircraft to keep links open between the mainland and Italian East Africa. The large three-engined Savoia Marchetti SM.82 and long-range three-engined Savoia Marchetti SM.75 and SM.83 usually handled the supply runs. On the eve of the surrender of the last Italian strongholds at Amba Alagi, Jimma and Gondar, the Duke of Aosta authorized the return of all aircraft still capable of making the journey. There were few that could make the journey, less than half a dozen. Some of the planes had been worn down due to months and months of continuous activity.

The Caproni Ca.148 I-ETIO

In any case, It was not difficult to find volunteer pilots and specialists, who would rather accept this difficult and almost impossible challenge rather than fall into the hands of the enemy. Earlier, a brilliant escape from Addis Ababa in late winter of 1941 saw three tri-engined Savoia Marchetti SM.73’s carry more than 40 pilots and specialists to Jeddah in Saudi Arabia and eventually to Benghazi, Libya. But now in Ethiopia, there remained only one aircraft that can handle the return. It was an old three-engine Caproni Ca.148, the I-ETIO, which, shortly before the fall of Jimma, had managed to flee from the last garrison of Italian East Africa: that of Gondar, defended by 40,000 men under the command of General Nasi.

You May Also Like:

Italy’s Secret Flight from Rome to Tokyo.

Italian Bombing of Manama, Bahrain

An Improved Version of the Caproni Ca.133

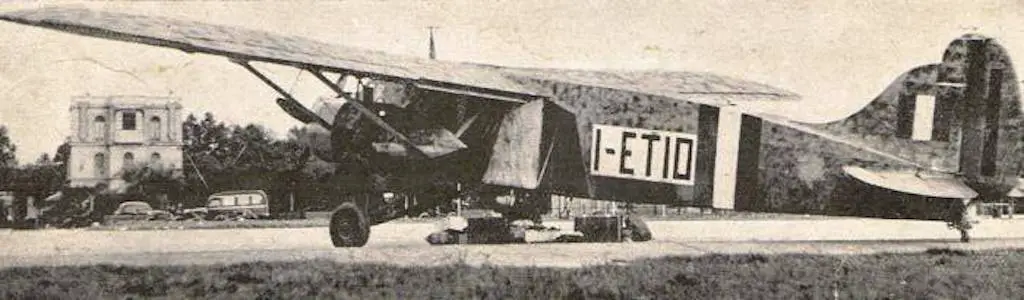

The I-ETIO was the last survivor of a group of six sets of the same type of Ca.148 variant. It was a similar, but a structurally improved version, of the famous Ca.133. A small but sturdy three-engined all-purpose Italian aircraft of the late 1930s. The first prototype of Caproni Ca.133 test flew in December 1934. It was a successful airplane, designed to transport troops or equipment and also used as a light bomber. The Ca.133 came equipped with three Piaggio P. VII C.16 engines with 430 horsepower. It obtained a top speed of 230 kilometers per hour and a range of about 1,000 miles.

Its normal load was 1,600 kilograms and a maximum weight of 6,700 kilograms. The Caproni Ca.133 could reach a maximum ceiling of 5,500 meters while equipped with an armament of (2/4) 7.7 mm Lewis light machine guns. The aircraft carried 470 rounds per weapon. Normally, the crew consisted of two or three men. Mass production of the aircraft began in late September 1935 and the Ca.133 obtained its baptism of fire during the outbreak of hostilities between Italy and Ethiopia. The aircraft proved fully capable to do its mission. However, in June 1940, it was already considered obsolete by more recent models.

Another view of the Caproni Ca.148 I-ETIO.

Restocking Uolchefit

Worn out from weeks of continuous flights and damaged several times by enemy hits, the “old Caproni”, as she was affectionately called by Italian pilots, obtained permission from General Pietro Gazzera to fly to Gondar. On 7 June 1941, the last Ca.148, filled with spare parts and seats, left Jimma in the company of the last two Fiat CR42. After several hours of flight, it landed at the airport of Gondar in the midst of an English bombardment.

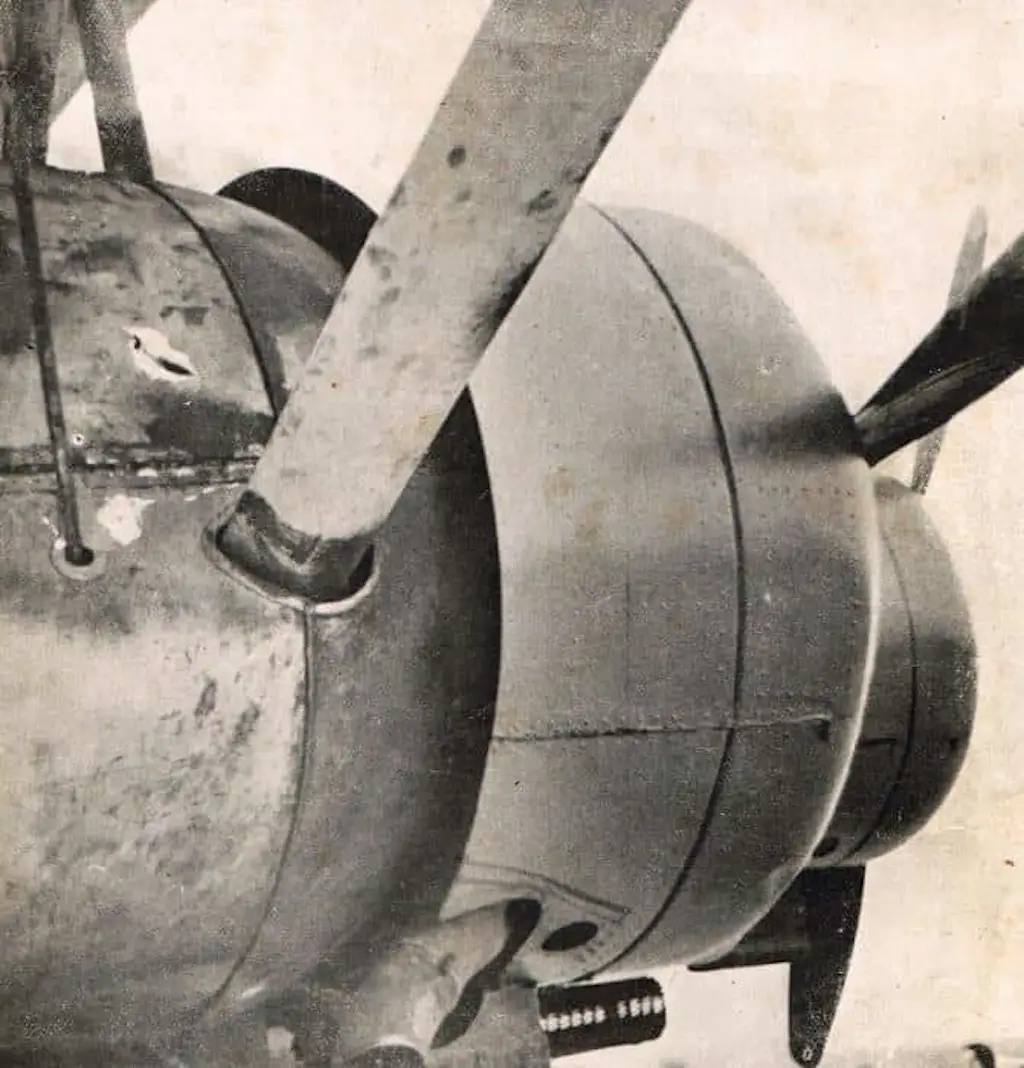

During their one week stay at the Presidio, pilots Lieutenant Nicola Caputo and Second Lieutenant Domenico Lusardi did not sit idly with folded hands. They performed three reckless runs in restocking the Uolchefit stronghold, now surrounded by British, South African, French and Ethiopian troops. These three missions resulted in about 200 enemy machine-gun bullet holes on the fuselage and wings of the Caproni. The damage reflected the courage involved in restocking this stronghold.

Visible damage from British anti-aircraft fire on the Ca.148 I-ETIO.

On 12 June 1941, Lusardi and Caputo were received by General Guglielmo Nasi. The General thanked them for their contribution to the defense of the fortress but insisted they abandon the area. The Gondar stronghold could not hold much longer and dangerously close to declaring a surrender. Lusardi and Caputo spent two days repairing and preparing the old “Caproni” for the long flight back to the motherland. Amazingly, the stronghold actually continued to resist until 27 November 1941.

Escape from Gondar

At 0130 on 15 June 1941, the I-ETIO took off from Gondar entrusting itself to fortune. The plane, restored to a civilian Ala Littoria, left in very bad weather conditions and with a broken radio. All onboard included pilots Lusardi and Caputo, radio operator Sargeant Emilio Di Biagio, Sargeant Major engineer Renzo Barilli, Clodomiro De Caro, three passengers, 700 liters of additional gasoline in barrels with pumps for manual transfer and several kilograms of urgent mail and top-secret documents.

The Caproni Ca148 with supplies laying on the tarmac.

Landing at Jeddah

According to the flight plan studied by Lusardi, the plane would fly to Jeddah, a Saudi port on the Red Sea, as a first stop. The aircraft would then continue towards Beirut and Rhodes. But this plan eventually became modified.

After seven hours of flight, characterized by strong squalls and high altitude turbulence, the I-ETIO flew over the Red Sea and reached the Arabian coast. The crew informed Saudi officials at Jeddah that a fire in the left side engine required them to land. They received permission. In reality, this fire already occurred at the Gondar airfield before they even started their trek to Jeddah. The plane landed in Jeddah at 0815 hours on 15 June.

Surrounded by an Arab militia, the Italian crew emerged wearing civilian clothes and promptly presented their falsified documents. These documents helped them avoid imprisonment. But the crew would remain restricted to a room at the airfield for four months.

During this time frame, the Italian embassy worked behind the scenes to get the aircraft released and refueled. During this endeavor, British officials kept pressuring the Saudi government to seize the aircraft and crew.

The crew of the Caproni Ca.148 I-ETIO needed to identify their next leg in the journey home to Italy and decide on it quickly.

No Fuel and Stranded

Elsewhere in the world, Syria and Lebanon became involved in an armed confrontation between Vichy French and British forces stemming from the failed coup in Iraq. Not wanting to bet on Beirut, the crew decided to fly towards Sollum, an Egyptian coastal town about 2500 kilometers away from Jeddah.

The priority now became to repair the engines and obtain the necessary fuel.

Encrusted with sand and salt after sitting idle for four months, mechanics Barilli and De Caro completely disassembled, repaired and cleaned all three engines of the Caproni. Barilli and De Caro then traveled from the airport of Jeddah to obtain a previously promised 1,000 gallons of fuel. The trip proved to be a disappointment. Arab officials, fearing retaliation by the British Consulate, granted only 400 gallons of fuel instead of the 1,000 promised.

A Miracle of Alchemy

Necessity is the mother of invention. Without losing his cool, the young engineer Barilli proposed a way to overcome the fuel problem. Barilli suggested a mixture of handcrafted aviation gasoline from car gasoline, benzol, and alcohol. These are substances the Arabs could sell without problems. Thanks to this miracle of alchemy, in just a couple of weeks, the Italian crew were able to produce 4,100 liters of a highly explosive but also highly toxic propellant. The crew installed six petrol drums welded in pairs onboard the plane to store this extra fuel. The aircraft now had enough fuel to reach friendly Italian controlled skies.

Nevertheless, Arab authorities, increasingly pressed by the British, would not allow the Italians to take off.

Eventually, thanks to the intervention of the Italian Consulate, and apparently a considerable fee, airport authorities finally granted permission.

At 1710 hours on 9 October 1941, the I-ETIO took off. The overloaded engines successfully burned the new fuel. It was a miracle the motors didn’t seize.

British Anti-Aircraft Fire Over Asyut, Egypt

The very slow Caproni Ca.148 I-ETIO took two hours before reaching the height of 2,000 meters and another five more before crossing the Red Sea. Eventually, the great silver river called the Nile came into view. But the adventure was not over. Somewhere above Asyut, British spotlights identified the plane and attacked it with anti-aircraft fire. The Ca.148 received a good deal of shrapnel, which by pure luck did not directly strike the internal tanks. However, windows had to be smashed on the aircraft with hammers to alleviate the unbearable smell of fuel oil in the air caused by the cracked fuel tanks.

Incredibly, the Caproni engines tolerated the petrol mixture, which for us humans was a real poison.

Emergency Landing and Trek Across Desert

Finally, at 0445 on 10 October, the I-ETIO-Ca.148 I reached Tobruk. It received a violent anti-aircraft fire from Commonwealth forces below. The Ca.148 I-ETIO escaped the attack by diverting its course to an interior route. With fuel tanks almost empty and its central engine seized, the Caproni Ca.148 managed to fly another 70 kilometers toward the direction of Ain el Gazala. It finally landed on a sandy clearing at 0625 hours. The crew emerged unscathed from the emergency landing only to endure a 36-hour hike under the scorching sun to reach the nearest Italian observation post in Derna.

Having recovered from the incredible trek across the desert, the Italian crew did not forget the Caproni I-ETIO. In fact, Lieutenant Lusardi remained behind to guard the tri-motor with a Beretta and a few bullets. Luckily, a mobile group of Bersaglieri recovered the aircraft and its keeper the following day.

The crew of the I-ETIO upon final landing at the Urbe airport.

Caproni Ca.148 I-ETIO Arrives Safely in Italy

After resupply and some maintenance work, the I-ETIO landed at the Derna airport on 12 October. At Derna they repaired the radio and central engine. However, the journey was not over. The next day, the Caproni finally took off for Italy and reached Rome-Urbe at 1415 hours on 19 October 1941. It was an odyssey of over 5,000 kilometers. Despite this exceptional journey, the skillful and stubborn Lieutenant Lusardi and his courageous crew never received an award. Indeed, nothing is known about the fate of these boys. Yet they helped write one of the most curious chapters of the history of Regia Aeronautica.

The indestructible Caproni Ca.148 I-ETIO continued to conduct transport service from the Airport Command Romano for quite some time after returning to Italy. There, the I-ETIO became affectionately called by its new nickname, the “Arab Phoenix”.

Translation assistant: Jeff Leser