A Plan to Ensure Secure Communications

The Italian High Command, Comando Supremo, suspected that the Allies had broken their international radio codes, and as radio was the most vital means to communicate with their Axis partner of the Pacific, the Italians needed to deliver new diplomatic codebooks to Japan to secure communications again. This was the motivation behind a tremendous wartime long-range flight from Rome to Tokyo, which is largely unheard of in post-war histories.

A Rome to Tokyo Air Route

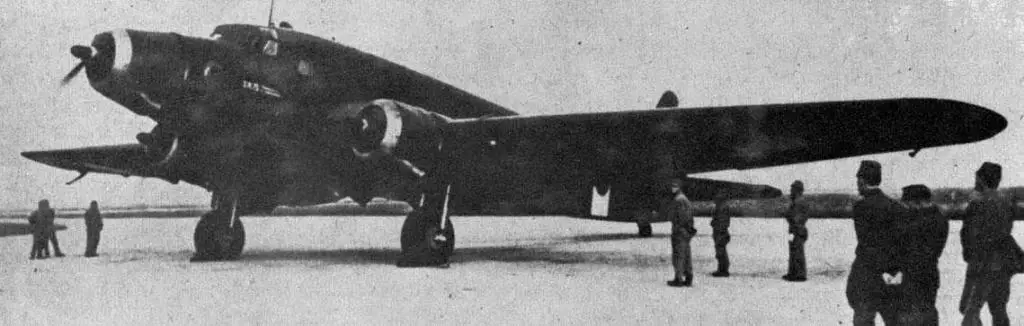

The possibility to effect a stable air-link from Rome to Tokyo had been envisaged by the Regia Aeronautica since late 1941 and by 29 January 1942, a written report was presented to the Air staff to determine the feasibility of this using three different routes with the new Fiat G.12 GAs (Grande Autonomia or Long Range). However, for the first experimental flight, a Savoia Marchetti SM.75 GA with Alfa Romeo 128 RC.18 engines was chose.

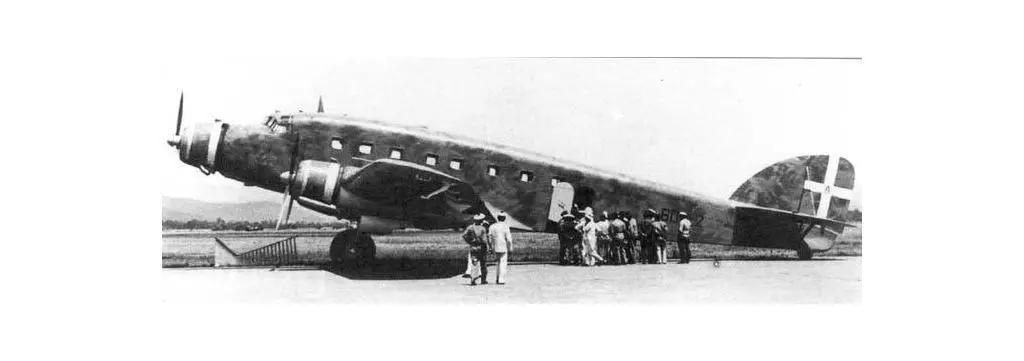

The Savoia Marchetti SM.75 Marsupiale.

The first SM.75 GA (serial-numbered RT MM.60537) was delivered on 17 March 1942, but it was decided to use it for a “symbolic” mission which consisted of dropping leaflets over Asmara, in the former Italian East African colonies.

This mission took place on 7 May 1942 starting from Guidonia (Rome). After a refueling stop at Benghazi, the aircraft took off on 8 May 1942 at 1730 hrs to drop its leaflets over Asmara at 0300 on 9 May 1942 and then landing safely back at Roma-Ciampino on 2130 hrs on the 9 May 1942.

The flight lasted 28 hours without any problem, confirming the feasibility of flying from Rome to Tokyo. Dr. Publio Magini was the navigator and co-pilot of that flight. At the time, Dr. Magini was considered one of Italy’s best pilots and was an expert in instrument flying. He had developed a celestial navigation system he called the ‘Star Altitude Curves’.

Setbacks

Unfortunately, the MM.60537 was badly damaged in an emergency landing only two days later. After their return to Guidonia, the crew of MM. 60537 were ordered to fly to Ciampino airfield, a mere 12 miles away. Shortly after takeoff, all three engines quit and the aircraft crash-landed. The pilot Captain Paradisi, and Dr. Magini escaped from the wreck before the fuel ignited and blowing up the aircraft. Paradisi lost a leg in the mishap and Dr. Magini suffered a serious leg injury that grounded him for a month.

You May Also Like:

Italian Bombing of Manama, Bahrain.

Incredible Journey of the Caproni Ca.148 I-ETIO

On 12 May 1942, Savoia Marchetti was ordered to speed up the production of the second Savoia-Marchetti SM.75 GA (MM.60539), as it was unofficially named like the former; “SM.75 RT” (Roma-Tokyo), and on 24 May a third SM.75 RT (MM.60543) was ordered to be built.

Due to several political and military problems, the flight was delayed and the load originally foreseen was steadily reduced until the aircraft had to leave with no load on board. The sheer challenge and propaganda value drove the continuation of the project.

The Day an Sm.75 Flew to Japan

At last, on 0526 hrs on 29 June 1942, the S.75 RT MM.60539 took off from Guidonia with the following crew: Ten.Col. Antonio Moscatelli, Cap. Mario Curto, Cap. Dr. Publio Magini, S.Ten. Ernesto Mazzotti (radio-navigator), and M.llo Ernesto Leone (Engineer). At 1410 hrs the SM.75 landed at Saporoshje, where the Italian Expeditionary Corps in Russia (CSIR) had established a refueling and radio base. It was an uneventful trip to Saporoshje, where Dr. Magini and his fellow crewmembers decided not to risk starting the second leg that afternoon to avoid interception. As a result, they spent the night at the airfield and took off the following evening at 2006 hrs on 30 June.

An image of the SM.75 GA in China.

Because of the fuel load, the aircraft could not get above 2500 feet and their airspeed was dangerously slow, making them a very vulnerable target. Pushing the aircraft threatened to overheat the engines and the crew watched anxiously as the temperature crept higher on the gauges.

It should be noted that Saporoshje was very near Rostov, where fierce fighting for control of the city was taking place. Soviet searchlights were everywhere, illuminating the night sky as the aircraft crossed the front. Almost immediately, they were spotted and beams of light tracked the aircraft. Streams of broken fire from Soviet anti-aircraft shells rose up to greet their aircraft which must have appeared as a slow easy target. Luckily for the crew, the Soviets scored no hits on the slow and low-flying aircraft. Dr. Magini and his crewmates endured the enemy’s AA fire for the next 100 miles. Dr. Magini understates this event in his journal:

It was not at all pleasant.

Escape from Soviet Air Space

Eventually, the shooting stopped and the aircraft was all alone in the dark night. Their route took them north of the Caspian Sea, then the Aral Sea, and Lake Balkhash. As morning approached, they had reached the Altai mountain range which separates the USSR from China. Flying low in a long valley, they finally found themselves over the Gobi desert. For hours, they flew over the vast uninhabited sand and wasteland that is the Gobi. This is where Dr. Magini’s ‘Star Altitude Curves’ celestial navigation was vital, as they had no aviation-coded maps of the Gobi desert.

Dr. Magini was of the opinion that they could have made it all the way to Japan but as they neared Japanese held territory, the Japanese insisted that they land at Pao-Tow-Chen, located west of Peking, near the Yellow River. This was necessitated by the Japanese security measures imposed over Japanese airspace after the Doolittle Raid two months earlier. Fighters patrolled the home islands day and night, ready to shoot down any planes without the Japanese insignia on the wings.

The Italians actually flew past Pao-Tow-Chen and were forced to turn back. As they did this, they found themselves in a torrential rainstorm and had difficulty finding their own position and the town. The storm let up long enough for Dr. Magini to determine their position and they found Pao-Tow-Chen under the cloud cover.

Arrival at Pao-Tow-Chen

At 1720 hrs on 1 July 1942, after a flight of 6,000 Km in 21 hours and 14 minutes, the Savoia-Marchetti SM.75 RT landed safely at Pao-Tow-Chen airfield in China. Japanese soldiers immediately took up stations around the aircraft as the crew got out. Japanese authorities and two Italian officials were waiting for them. The Italians were Captain Roberto de Leonardis, the Naval Attaché and Enrico Rossi, an interpreter.

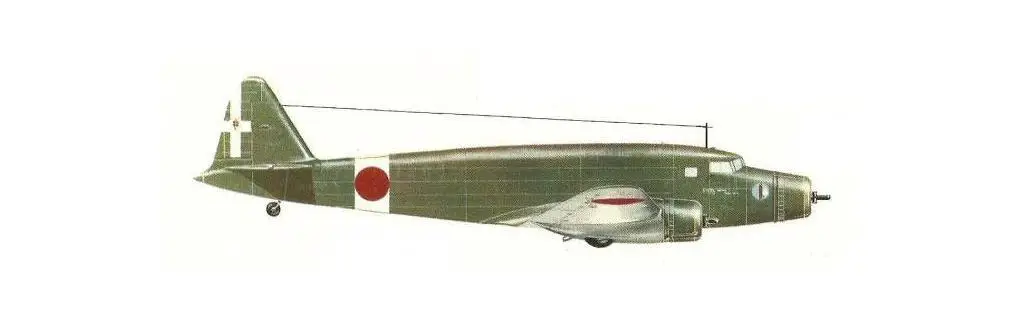

A diagram of the Sm.75 GA with Japanese markings.

They were ushered to the local hotel, which ironically, was a replica of the Pompeii houses outside of Naples. Each crewman was “given” at least two Geisha girls who bathed them and washed their dirty garments. While they waited for their clothes, the Italians wore kimonos, which only added to the surrealism they felt in this environment.

Dr. Magini and his fellows were obliged to layover for a day, waiting for a Japanese Air Force guide to arrive from Tokyo. The flight paths to and from the home islands changed daily and any aircraft at the wrong location or altitude or on the wrong course ran the risk of being shot out of the sky. While they waited, Japanese ground crews painted the rising sun insignia on the wings and fuselage of their aircraft.

A Stop in Tokyo and Successful Return

They finally took off for Tokyo around 7:00 AM on July 3. The Japanese flight guide, a captain, accompanied them and instructed them on exactly what course they should take. Their route took them over Peking, Dairen, Seoul, Yonago, and Tokyo; a trip of 2,700 km. They landed at the Tachikawa air force base near Tokyo at 1704 hrs.

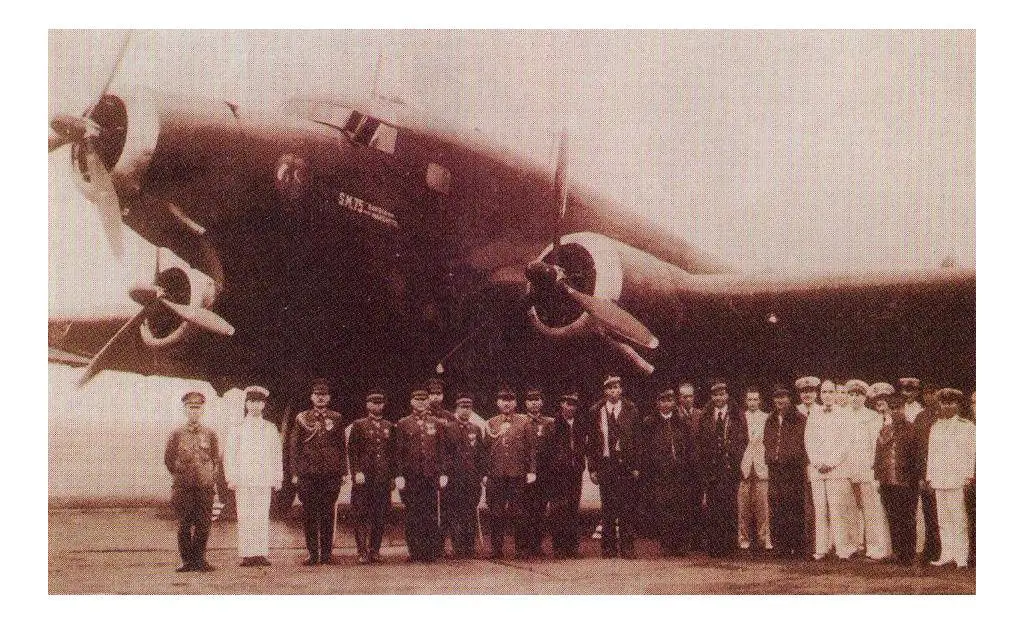

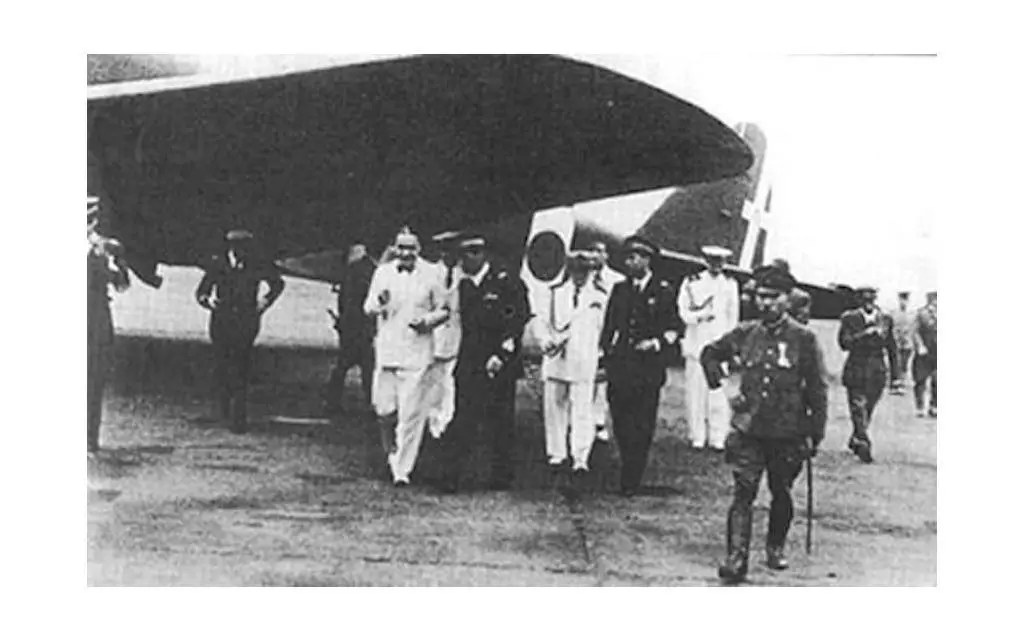

The crew of the Savoia Marchetti SM75 GA RT and Japanese officials after their landing in east Asia.

After several days between ceremonies and planning of the return flight, the aircraft left Tokyo, still without any load onboard, at 0520 hrs on 16 July 1942, reaching Pao-Tow-Chen at 1540hrs. There the Japanese provisional markings were removed and the aircraft took off with a maximum fuel load. The takeoff was conducted with some difficulty, due to the short runway at 2145 hrs GMT on 18 July. The aircraft landed at Odessa at 0210 hrs GMT on 20 July. At 11.00 hrs on the same day, the S.75 RT took off again, reaching Guidonia at 17.50 hrs. Mussolini himself was waiting for the arrival of the plane.

The SM.75 GA lands in Tokyo. Note the Japanese markings on the aircraft.

A Second Route That Never Materialized

Upon the request of the Japanese, the whole flight had to be kept secret. But news came out five days later in Italian newspapers and the Japanese immediately decided to stop any further flights on the original route. The Japanese were interested in studying a more southerly route. The route studied would include Rome, Rhodes, southern Bulgaria, northern Turkey, Caspian Sea, north-eastern Iran, Afghanistan, south of the Himalaya Mountains, over the Gulf of Bengal, and finally reaching Rangoon. This study delayed any further progress and the next flight scheduled for August 1942 using the second SM.75 RT MM.60543 was canceled.

The crew after their return to Rome: L-R Marshal Ernesto Leone, Captain Publio Magini, Lt Col Antonio Moscatelli, Major Mario Curto and Second Lieutenant Ernesto Mazzotti in front of the SM. 75 GA used for the flight. Ciampino, July 1942 (Photo by Mondadori Portfolio via Getty Images)

Further flights would have employed the new Fiat G.12 RT, but the difficulties created by the Japanese concerning the Southern route and with securing adequate radio and navigational aids, especially in Rangoon, delayed things until on 17 November 1942. It was then that the Italian government, and the Regia Aeronautica, decided to put an end to the whole project.

References:

E-mail in “12 O’Clock High!” web forum and further correspondence with Ferdinando D’Amico Summer 1993 issue of Military History Quarterly: Narrative by Dr. Publio Magini

Dr. Kenneth Werrell in “World War II German Distance Flights: Fraud or Record?” in Aerospace Historian, XXXV, No. 2 (Summer/June 1988), pp. 111-16 debunks the myth of Ju 290 flights to Japan/Manchuria. A Ju-290 could in theory fly one way to Manchuria, and such flights were at one time envisioned. The story got started through disinformation provided by a captured German serviceman, Unteroffizer Wolf Baumgart, which was duly recorded in Ninth Air Force A.P.W.I.U. Report 44/1945. As well, research by Gunther Ott, the leading authority on the type, has established the careers and fates of all these long-range modified aircraft and ascertained that no such flights were actually carried out.