Background of the Spica Torpedo Boats

The background of the Spica Class Torpedo Boat provides a look into how political affairs affected naval affairs. After the immense cost of the naval arms race at the turn of the century, no one wanted a repeat. Therefore, numerous naval treaties were put into effect to limit the navies of the great powers. The most famous of these is the Washington Naval Treaty, but there were others. The creation of the Spica Class Torpedo Boat saw the influence of a combination of factors. Political concerns, economic concerns, and the unique strategic position of Italy combined to make their construction a prudent decision.

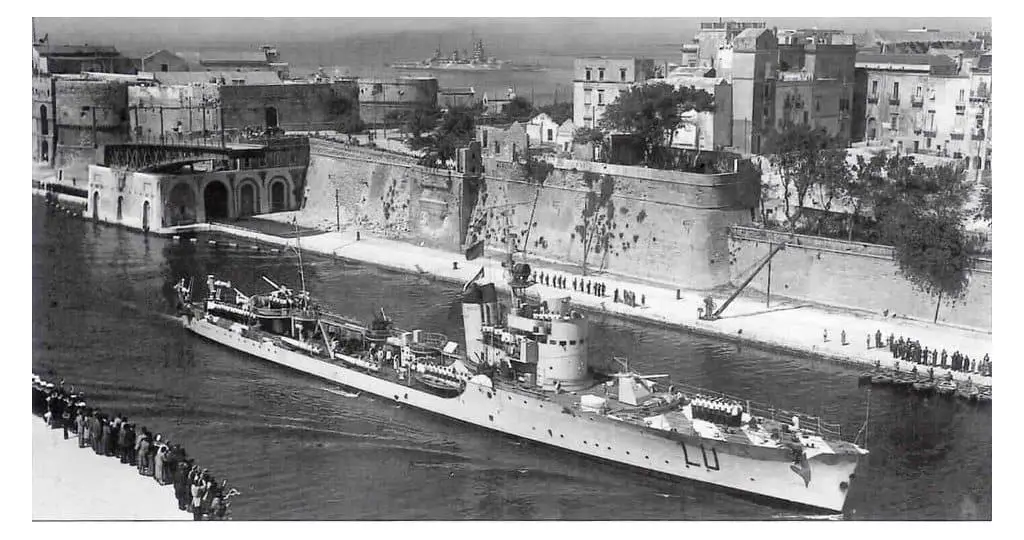

Spica class Torpedo Boat Climene.

The London Naval Treaty of 1931 had allowed for unconditional, limitless construction of vessels under 600 tons. In oceanic waters, such ships would have limited utility, and the tonnage limitation imposed several practical challenges. The weight quota places severe limitations on between speed, armor, armament, and range. However, Italy only had the need to operate within the confined waters of the Mediterranean.

Construction on the Spica Class

Their unique geographic position and strategic situation gave short-ranged, fast, light vessels unusual utility. These circumstances produced the thirty-two torpedo boats of the Spica Class, constructed between 1934 and 1937. Small, fast, and quite well-armed, they’d make for effective convoy escorts, and free up destroyers for fleet actions. While some charge that the Regia Marina lacked aggression and energy, the record of the Spica Class stands to the contrary. They and their crews went on to demonstrate this in many actions throughout the Mediterranean. When they ended up in surface combat, they often hit above the limits implied by their 600-ton weight limit.

Displacement

In all fairness, the design of the Spica Class didn’t actually observe the 600-ton weight limit. A completely empty hull weighed 720 long tons, and on a standard load, this figure increased to 795. A full load for combat could weigh as much as 1,040 long tons. In all, they were still quite light, and their 19,000shp engine enabled a combat speed of 34 knots.

Their frame measured 83.5m long, with a draught extending 2.55m below the waterline and a beam of 8.1m. The idea that ‘speed is armor’ is a silly one when applied to tanks or battleships. However, the small size and speed of these ships made them quite a hard target to hit.

Armament

Their primary armament consisted, at first, of four 450 mm torpedo tubes in single mounts, and three 100mm dual-purpose guns. For anti-submarine purposes, they carried depth charges and 2-4 depth charge throwers. Additionally, they could carry 20 mines if the mission called for them. For dedicated anti-air defense, their armament wasn’t entirely standardized. They carried up to twelve anti-air guns, a mix of 20 mm cannon and 13.2 mm machine guns in dual and single mounts. In short, it differed by the subclass, of which there were five.

Libra Torpedo Boat in 1939.

For instance, the study of David Greentree (2016) provides some insight into the matter. The subclass was derived from the location and time of production, with variance in anti-air and torpedo tube layout between them. The Alcione Group arrayed their torpedoes facing forwards, for instance, rather than to the sides. Additionally, the Alcione Group differed within itself as to the use of double or single mounts. Eventually, the single tubes were done away with and machine guns were replaced. This resulted in greater uniformity among the wider class by 1941, which all possessed double torpedo tubes and 20mm cannons. The same year saw the first outfitting of sonar on the ships, greatly increasing their effectiveness against British submarines.

Service History In WWII

One might say that the Regia Marina has gotten the short shrift in popular history, as a whole. If this is true of the excellent Littorio battleships or the Zara cruisers, it’s doubly true of this humble workhorse. The Spica Class torpedo boats were unsuitable for large fleet actions, which can only exacerbate their obscurity among casual observers. However, they were instrumental in the war for the supply lines. They played a part in many small engagements, and a Spica was the first ship to spot the British prior to the Battle of Cape Spartivento (Battle of Cape Teulada).

The torpedo boats suffered their defeats, particularly earlier in the war. At the Battle of Cape Passero in October 1940, faulty tactics saw several torpedo boats lose an opportunity to sink a British cruiser. While each ship fought aggressively, HMS Ajax suffering numerous hits from their main guns, they failed to combine their efforts. Particularly when it came to the use of torpedoes: failing to effectively employ their torpedoes as a unit led to all torpedoes being evaded. As a result, they suffered a nasty defeat, losing two boats and a destroyer.

Small-Unit Successes

However, they’d fight more effectively in the coming year. In the Battle for Crete (20 May-01 June 1941), Spica torpedo boats interdicted British convoys and escorted German reinforcements to the island. The disaster at the Battle of Cape Matapan (Battle of Gaudo) made Supermarina hesitant to send capital units, for good reason. But, they were willing to send small ships, with excellent results. The Spica class torpedo boat Lupo fought valiantly in the battles for Castellorizo, a small island off the Turkish coast. In opposition to Operation Abstention, it alone engaged a force of eight heavier British ships from behind a smokescreen. Impressively, Lupo held them at bay long enough to save several ships of a convoy, ultimately contributing to the British defeat.

A photo of Lupo following the clash with HMS Ajax, Orion, and Dido. Note the damages to the hull.

As late as 1943, the Spica class torpedo boats fought with distinction at the Battle of the Cigno Convoy. In the twilight hours of Panzerarmee Afrika, two torpedo boats encountered a pair of British destroyers while escorting a tanker. British fire quickly crippled Cigno, one of the torpedo boats, but Cigno continued firing her main guns until a torpedo finished her off. Cassiopeia fought with great zeal against both destroyers, launching torpedoes at HMS Paladin and raking Pakenham with her main guns. In spite of fires onboard, Cassiopea continued fighting until both sides withdrew. In short, she delivered such severe damage that Pakenham was beyond saving, prompting the British to scuttle her.

Spica Sub Classes

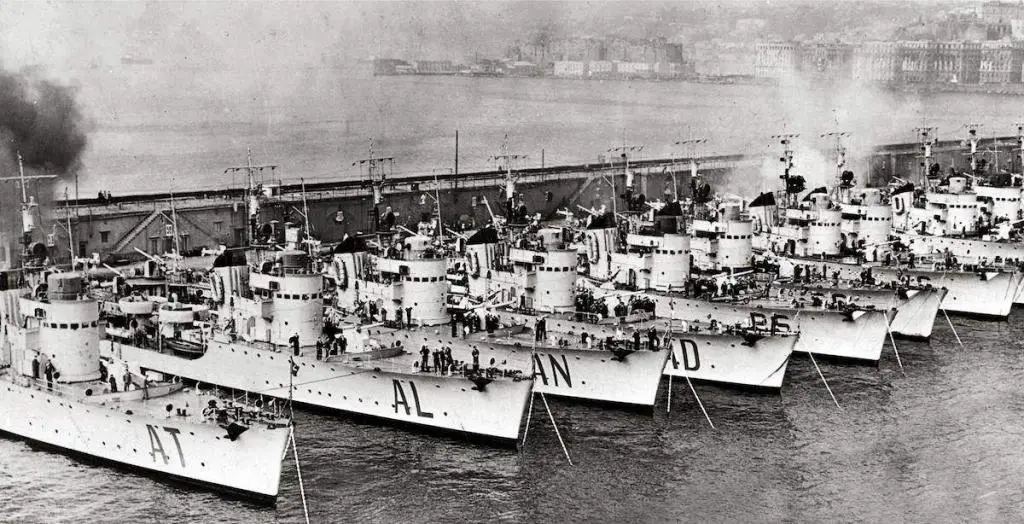

Spica Class Torpedo Boats moored in port. From (L) to (R) left to right we clearly see Altair, Aldebaran, Antares, Andromeda, and Perseo.

Alcione: Arione, Alcione, Aretusa, Ariel, Calliope, Circe, Clio, Libra, Lince, Lira, Lupo, Pallade, Partenope, Pleiadi, and Polluce.

Perseo: Aldebaron, Altair, Andromeda, Antares, Perseo., Sagittario, Sirio, and Vega.

Climene: Canopo, Cassiopea, Castore, Centauro, Cigno, and Climene.

Fate of the Spica Class

Throughout the war, various causes and engagements saw the loss of 23 of the original run of 32. However, the remainder stayed in service in the cold war era. The final Spica Class torpedo boats decommissioned as late as 1964.

Specifications

| Class | Spica |

|---|---|

| Type | Torpedo Boat |

| Built | 1934-1937 |

| Displacement | 795-1040 tons |

| Length | 273 ft 11 in (83.5 m) |

| Beam | 26 ft 7 in (8.1 m) |

| Propulsion | 19,000 shp (4,200 kW) 2 boilers |

| Speed | 34 knots |

| Crew | 116 |

| Armament | (3) 100 mm (4 in)/47 caliber dual-purpose guns (12) 20 mm cannon and 13.2 mm machine guns (4) 450 mm (18 in) torpedo tubes 20 mines |