The Battle of Cape Spartivento (Italian: Battaglia di Capo Teulada), on 27 November 1940, was the first significant naval action in the Mediterranean after the Raid on Taranto. This engagement proved to be an inconclusive clash between the two “Royal Navies” of the theatre. It was, however, seen as a missed opportunity by Italian leadership.

HMS Manchester receiving fire from Italian vessels during the Battle of Capo Teulada. Image take from HMS Sheffield.

Context

Following the Taranto raid, the British launched Operation White on 17 November 1940. The goal was to reinforce Malta with 12 Hurricane fighters launched from HMS Argus. The presence of the Italian battlefleet led the British to launch their aircraft too early. This resulted in only a few aircraft landing on Malta. Because of the early launch, one Skua and eight Hurricanes were lost at sea after running out of fuel.

With Malta in urgent need of supplies and weapons, the Royal Navy mounted a resupply operation with multiple objectives:

- Resupply Malta.

- Ensure the transfer of warships required to fight in the Atlantic.

- Move ships from Malta to Alexandria.

The quest to resupply Malta resulted in two distinct operations, one naval formation departing from Gibraltar (Operation Collar) under Admiral James Somerville and the second leaving from Alexandria (Operation M.B.9) under Admiral Cunningham.

Early Allied Movements

M.B.9 took place between the 23 and 27 November 1940. The operation went almost unopposed by the Italians, except for scattered torpedo bomber attacks from the Aegean islands. On the 27th, Cunningham dispatched the convoy to Malta. At the same time, the battleships Ramilles, the cruiser Berwick, Coventry, Newcastle, and five destroyers (Force D) headed for the Sicilian channel and the rendezvous point with Somerville south of Sardinia.

Admiral James Somerville

Meanwhile, on 25 November 1940, Somerville departed from Gibraltar. Italian agents based in Algeciras immediately reported the ship’s movements to the Navy high command. Somerville’s battle force consisted of the battlecruiser Renown, the aircraft carrier Ark Royal, the cruisers Sheffield, Despatch, and nine destroyers.

Recognizance and intelligence reports coming to Rome confirmed enemy movements both in Western and Eastern Mediterranean. These reports suggested another complex operation aimed at resupplying Malta. The alerted Italian battlefleet received orders to depart by midday of the 26 November.

Italian Movements

Admiral Inigo Campioni received orders to engage the enemy only under favorable circumstances. These orders provided him little room for maneuver and dependent on the final decision coming from the high command (Supermarina). It is important to remember that in late November 1940, the Regia Marina had only two operational battleships available (Vittorio Veneto and Giulio Cesare), thus making these assets extremely precious.

Squadron Vice Admiral Inigo Campioni. Image: Public Domain.

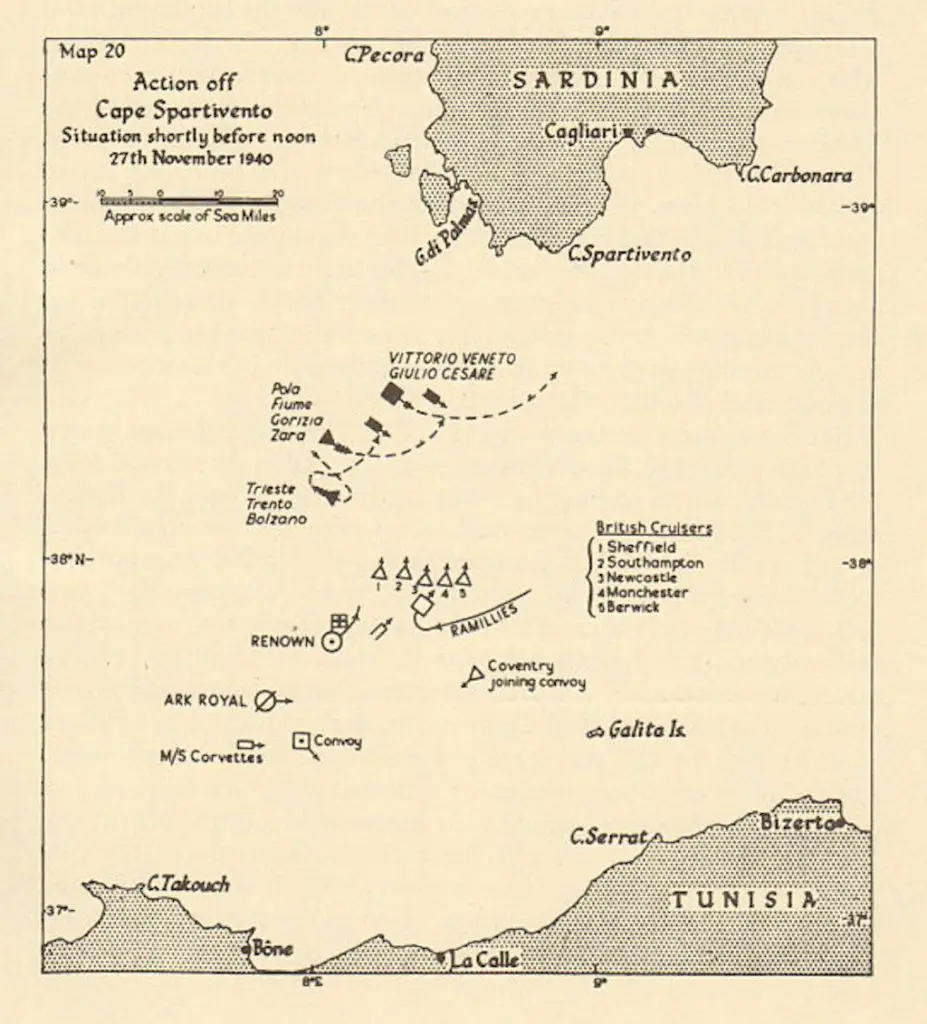

Campioni departed Naples with a force consisting of the only two battleships available, the cruisers Pola, Fiume, Gorizia, and 11 destroyers. Meanwhile, the cruisers Trieste, Trento, Bolzano, and three destroyers departed Messina. The two fleets gathered and sailed south-west for most of the day. During the night, the torpedo boat Sirio, patrolling the Sicilian channel, reported its attack on a formation of enemy ships cruising North-West.

Cruiser Bolzano, during the battle of Capo Teulada.

Campioni wrongly believed until the morning of the 27th that the enemy forces attacked during the night by Sirio was Admiral Somerville’s force from Gibraltar. At 9:45, Bolzano’s seaplane sighted Somerville’s force, heading eastwards. One hour later, without any further contact, Campioni changed course, aiming to intercept the warships that crossed the Sicilian channel. Soon after, a seaplane from the Gorizia also sighted Somerville’s naval formation. The sighting provided Campioni confirmation that the two forces were attempting a rendezvous. This element, together with the presence of an enemy aircraft carrier, probably convinced Campioni the balance of power was not in his favor. Thus risking his battleships was not an option.

At 11:50, he signaled Supermarina his intentions to withdraw. He asked for a confirmation which only arrived at 12:56 in vague terms.

Battle of Cape Spartivento

Between 12:00 and 12:15, Campioni ordered the fleet to change course and direct for the bases. Meanwhile, Admiral Angelo Iachino, commanding the cruiser divisions, sighted enemy ships and ordered to open fire. Gunfire exchanged between British and Italian cruisers. the HMS Berwick obtained two hits by Italian 8 inch shells while the Italian destroyer Lanciere became immobilized by a British shell.

HMS Berwick received damage in the Battle of Cape Spartivento.

During the ensuing action, Iachino received Campioni’s order to withdraw. So he reluctantly changed course attempting to reunite with the Battleships. Campioni decided to provide aid to the cruisers by bringing the Vittorio Veneto within the firing range. At 12:38, torpedo bombers from the Ark Royal attacked the Italian battleships, scoring no hits. At 13:00, once the Italian fleet regrouped, the Vittorio Veneto opened fired on the British at distances between 28,000 and 32,000 meters. It scored no hits. The two fleets continued distancing themselves. When Somerville fully regrouped with Force D, he turned back, setting a course to Gibraltar.

The destroyer Lanciere, hit in the engine compartment during the battle, was towed back to Messina. It is interesting to note that Admiral Iachino ordered Admiral Sansonetti to provide aid to the Lanciere using his entire division. This order is similar to the much more fatal one given during the night of the Battle of Cape Matapan.

Battle of Cape Spartivento Map.

Aftermath of the Battle of Capo Teulada.

The battle (perhaps more a brief clash) of Cape Spartivento was an inconclusive action in the battle for the Mediterranean. The Italians did not stop British operations. And the Italian military leadership prevailed the feeling that they missed a significant opportunity. Senior leadership deemed Campioni’s course of action to be excessively cautious. Campioni avoided a fight that could have stopped the Royal Navy.

In Campioni’s defense, he was responsible for the only two remaining operational battleships. Additionally, in following Supermarina’s directives, the engagement did not appear to be under favorable terms. Also, scattered air-recognizance and communication transmission delays severely hindered Campioni’s ability to evaluate the situation.

The main consequence of Cape Spartivento was ultimately the replacement of Campioni with Iachino as commander of the battlefleet. Additionally, the substitution of Admiral Cavagnari with Admiral Riccardi as head of the Regia Marina.

Sources

Giorgio Giorgerini, La Guerra Italiana sul mare: la marina tra vittoria e sconfitta 1940–1943, Edizione Mondadori (2001).

Riccado Nassigh “Le Battaglie Navali Italiane”, Delta Editrice (2011).