From November 1942 until May 1943, the Italian navy fought a desperate struggle to resupply the Axis forces in their last stand on North African soil.

Beginning of the campaign

On the 8th of November 1942, the Allied landings in French North Africa and the arrival of consistent American forces in the area, changed once and for all the strategic outlook of the Mediterranean theatre. The Axis forces retreating across Libya, following the defeat at El Alamein, now faced the threat of being taken from the rear by the Allied armies advancing from Algeria. The Italian and German leadership quickly took the decision to occupy the French-controlled Tunisia, in an attempt of halting the enemy advance and maintain a strong presence in North Africa (delaying as much as possible an assault against continental Europe). The Axis reaction was rather quick, already one day after the Allied landings, German paratrooper units landed near Tunis, to establish a first foothold.

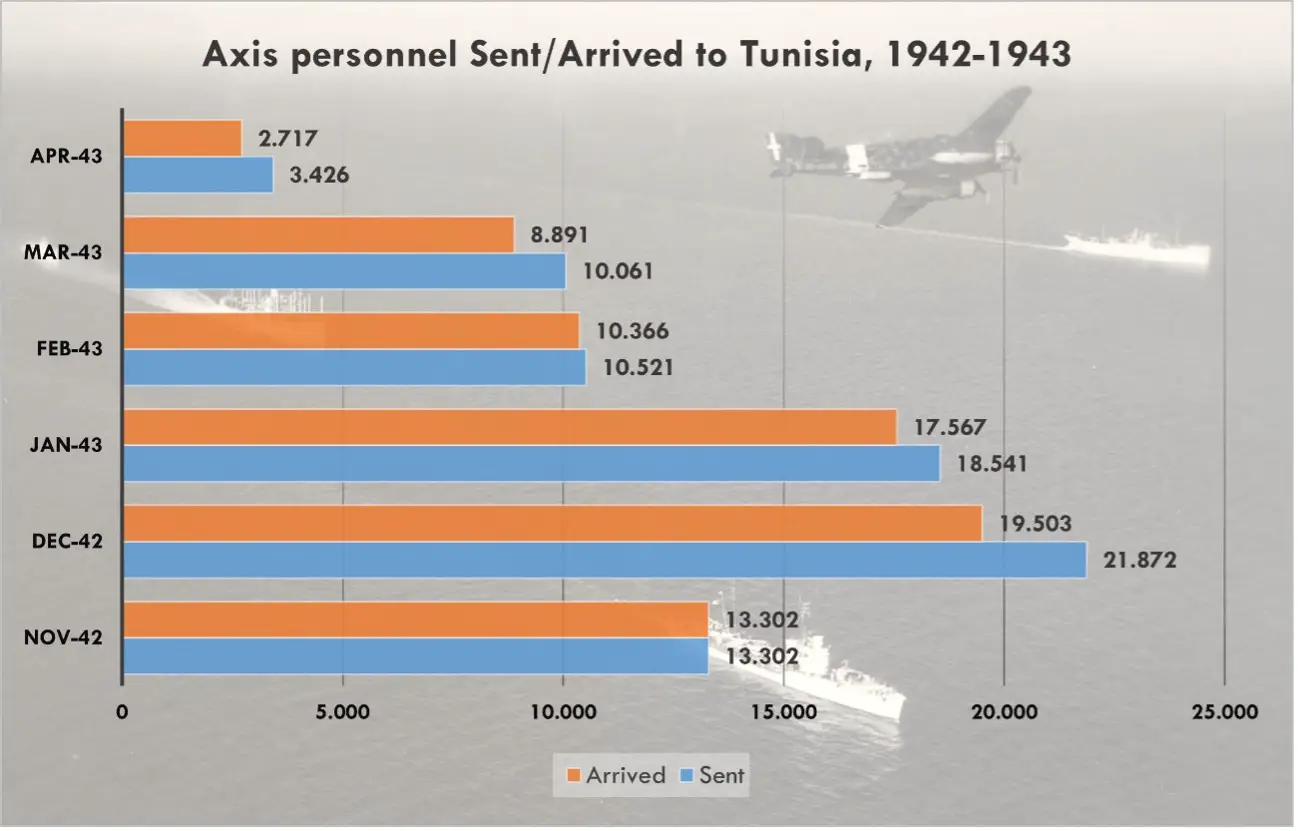

The first convoy, organized by the Italian navy (Regia Marina), arrived in Bizerte on the 12th of November. Between the 12th and 16th of November, a total of 3,682 men, 450 vehicles and 2827 tons of supplies were transferred by sea to the ports of Tunis and Bizerte. For the rest of that month, no losses were inflicted on the Italian convoys, and this put the Axis forces in the position to halt the Allied spearheads that advanced from Algeria.

In that period, the Italians also laid down a vast minefield west of Bizerte that extended for several miles to the northeast. This new minefield, coupled with an older one stretching from Marettimo Island to Cape Bon, created a corridor aimed at protecting the axis supply routes.

Since the best and fastest merchant ships had been lost during the previous years, Italian destroyers were very often used to ferry military personnel and supplies, granting a faster influx of the needed men and materials. This emergency measure was also taken due to the attrition caused by the merchant ships and the inability to repair the damaged ships at a sufficient pace.

A new phase

The Allies failed to secure Bizerte and Tunis before the Axis, but slowly stabilized their positions and logistics, establishing airfields and naval bases from where they could threaten the Axis convoys. The British Royal Navy formed the “Force Q” in the port of Bône (today known as Annaba), made up of the light cruisers HMS Aurora, Sirius and Argonaut and the destroyers HMAS Quiberon and HMS Quentin.

This force successfully engaged an Italian convoy and its escorting warships near the Skerki bank, on the 2nd of December 1942. Three Italian merchant ships and a German transport craft were heading to Bizerte, escorted by the destroyers Da Recco, Camicia Nera, Folgore and the torpedo boats Clio and Procione. In the darkness of the night, the allied warships located the convoy and opened fire, hitting the transports first. The Italian escorts attacked with torpedoes and gunfire but inflicted only minor damage while the destroyer Folgore was sunk. Subsequently, the destroyer Da Recco attempted another attack but was crippled by the cruisers’ gunfire. The Da Recco managed to escape with the rest of the escorts while the convoy was lost.

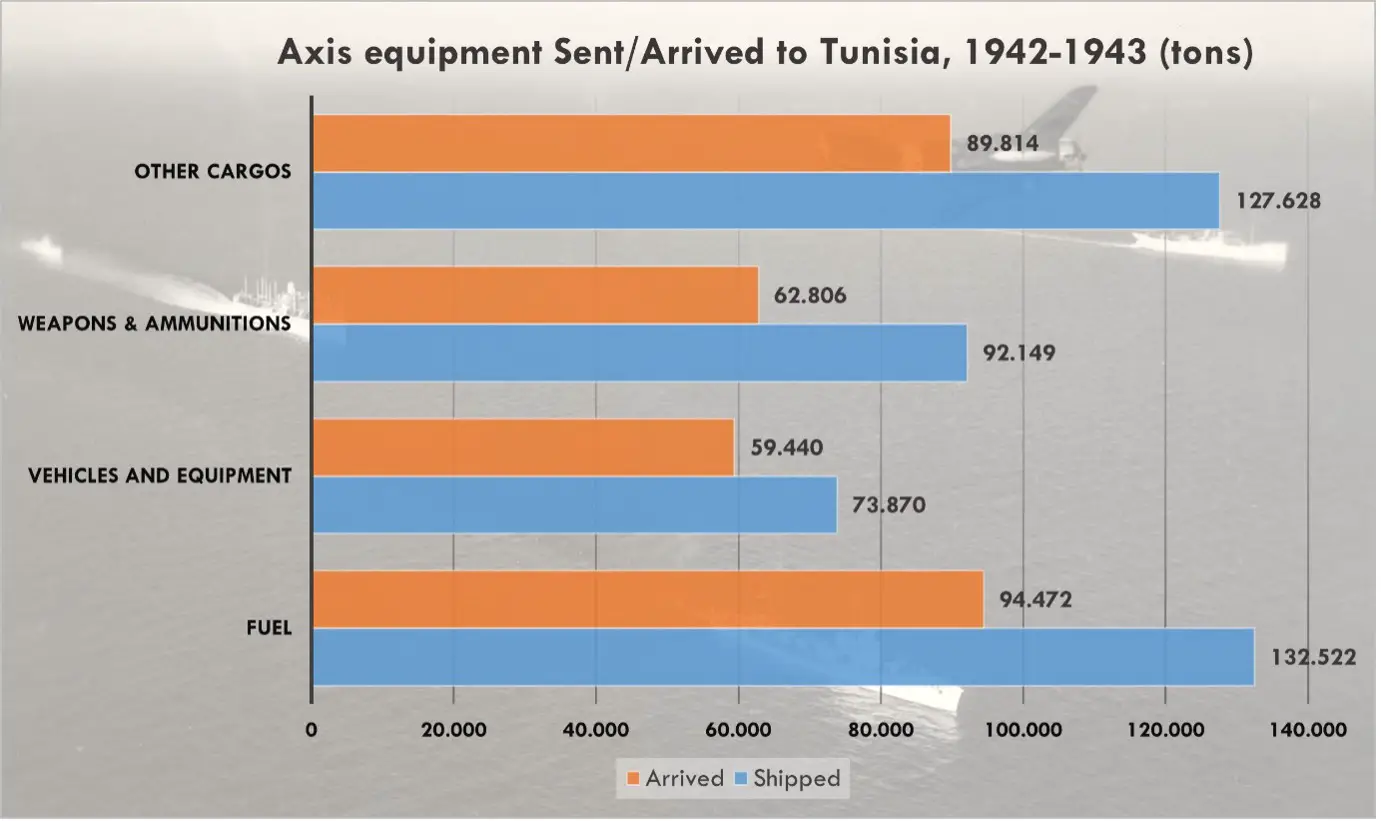

In that period, the British managed to lay another minefield, inside the corridor created by the Italians, and this will later provoke severe damages and losses among warships and merchant vessels. From the beginning of December, American and British aircraft operating from newly established North African airfields began their offensive against the Axis convoys and soon losses at sea started to increase. Besides that, Allied airpower also targeted the ports in Axis hands, where they sunk or damaged a consistent number of merchant ships, barges and other transport crafts. However, during December, the Italian navy push through the Sicilian channel with 71% of the supplies shipped and 89% of the men. Admiral Cunningham himself acknowledged that the Allies had not been able to cut off the Axis maritime routes.

The destroyer Ascari hit by a mine, prior to sinking (Bagnasco collection)

The fight grew in intensity with the new year and although delivery rates improved in January (94% for men and 79% of supplies) and February (98% of men and 77% of supplies), the losses at sea and the attrition on the surviving ships had exhausted the Regia Marina like never before. This was exemplified by the nickname given by sailors to the route towards Tunisia: “la Rotta della Morte” (the route of death).

Grim prospects

On the 11th of March 1943, the Regia Marina high command (Supermarina) assessed that only 15 warships (among destroyers, torpedo boats and corvettes) were available for convoy escort duties. March was indeed a black month for the Italian navy since it lost 28 merchants and 7 warships. By the end of the month, the Navy’s high command had concluded the navy could not afford to resupply Tunisia any further, without compromising its capabilities to mount any future naval operations.

The corvette Procellaria, hit by a mine, prior to sinking (Bagnasco collection)

Despite the grim predictions, the convoy runs continued in April and on the 16th of that month a curious surface action took place. The Italian torpedo boats Cigno and Cassiopea, were navigating ahead of a convoy when they sighted in the darkness two ship silhouettes, they closed the distance and opened fire. A 100mm shell landed on the HMS Pakenham causing severe damage while the Cassiopea engaged the HMS Paladin. Hearing the sound of battle, the convoy reversed course and reached safety. To the south, the Cigno was hit in return by the Pakenham and torpedo stroke amidship, breaking the Cigno in two. The stern section remained afloat for a while, in time for landing a final 100mm shell on the Pakenham that caused the flooding of the engine compartment. After exchanging fire with the Cassiopea, the Paladin disengaged, wrongly believing they were facing a light cruiser, thus the torpedo boat escaped safely. The Paladin towed the crippled Pakenham at slow speed, but eventually, the ship was scuttled in the morning, fearing an upcoming air attack after the formation was spotted by enemy aircraft.

Despite the action fought by Cigno and Cassiopea, the overall convoy situation was deteriorating. In April, of the 3,426 men who departed from Italy, only 2,617 arrived while only 58% of the shipped supplies landed in Tunisia.

Epilogue and figures

A little stream of supplies arrived up until early May, right before the surrender of the German (11th of May) and Italian forces (13th of May) in Tunisia. The campaign had proven costly for the Regia Marina, in terms of ship losses, with around 224,000 tons (1) of merchant ships sunk at sea, 7 destroyers, 5 torpedo boats and a few other corvettes and minor warships. Despite the losses, the Regia Marina managed to land 71% of the men shipped and 93% of the men. Of the 77.541 men transferred by sea to Tunisia, 72% (55,973) were ferried by Italian destroyers.

In the space of 7 months, the Italians recorded 11 attacks by surface ships, 75 by submarines and 167 by aircraft. Now the Mediterranean battle of the convoys was over.

After the Tunisian campaign, the Regia Marina was left with very tiny fuel reserves and lacked sufficient numbers of escort vessels for its battleships and cruisers.

(1) Data from “Dati Statistici”, quoted in the sources

Sources

Giorgerini, G. (2001). La Guerra Italiana sul mare, La marina tra vittoria e sconfitta 1940-1943.

Hammond, R. (2020). Strangling the Axis: The Fight for Control of the Mediterranean during the Second World War.

O’Hara, V. P. (2008). Struggle for the Middle Sea: The Great Navies at War in the Mediterranean Theater, 1940-1945.

Sadkovich, J. (1994). The Italian navy in World War II.

USMM. (1950). La Marina Italiana nella seconda guerra mondiale, Volume 7, Dati statistici.