After two years of advances and retreats, the Second Battle of El Alamein (23 October – 11 November 1942) marked a turning point in the North African front. The Axis defeat paved the way for an Allied invasion of Europe.

Military historians often divide the battle into five phases:

- Break-in (23-24 October

- The Crumbling (24-25 October), t

- The Counter (26-28 October)

- Operation Supercharge (1-2 November)

- Break-out (3-7 November)

Background on the Second Battle of El Alamein

The 1942 summer campaign of the Italo-German army in Africa, led by Erwin Rommel, resulted in a series of astonishing successes. In May-June, the victory at Ain-el-Gazzala led to the fall of Tobruk, which seemed to open the gates of Egypt. Rommel started chasing the British 8th Army across Egypt, to secure North Africa for the Axis.

The decision to pursue the enemy into Egypt was in sharp contrast with the original Axis plan. The original plan called for an air and amphibious assault on Malta following the capture of Tobruk. This plan would consequently halt the advance towards Alexandria. However, Rommel managed to convince Hitler that the Axis had a unique opportunity that should not go to waste. Persuaded by Rommel’s arguments, Hitler subsequently convinced Mussolini to forego the attack on Malta and continue the march into Egypt.

Later in the summer, the First Battle of El Alamein and the Battle of Alam el Haifa proved Rommel wrong. The 8th army was not defeated. On the contrary, they halted the axis advance, dramatically reducing Rommel’s fuel reserves. This failure did not sit well with the Desert Fox. He also unfairly accused the Italians of his failure. After Alam el Haifa, the Italo-German army dug in and prepared for the inevitable British counter-offensive.

Related: First Battle of El Alamein

A lone Italian soldier stands guard at the Qattara Depression.

While the Allied build-up progressed, Axis forces laid down a vast minefield on the front line. It ran from the coast down to the Qattara Depression in the south, passing in front of the small train station of El Alamein. This deadly region became known among soldiers as the Devil’s gardens.

El Alamein Train Station in 1942.

Prelude to Battle

Among Italian and German ranks, soldiers and officers were well aware that an attack was coming. They expected the attack in early October. However, the over-cautious Montogomery decided to wait for more reinforcements to deal a killing blow to the Italo-German Army, now led by Georg Stumme. Rommel had flown back to Germany on sick leave.

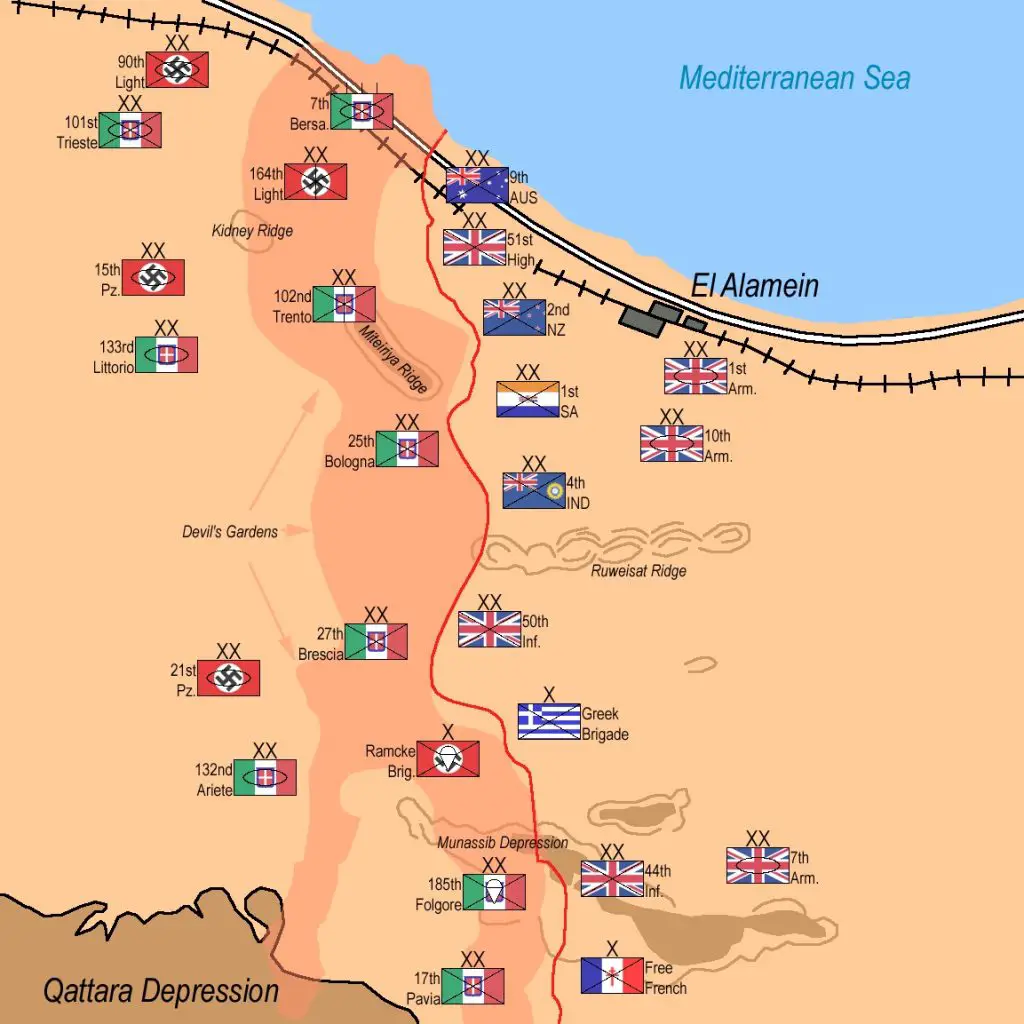

The Axis frontline was guarded in the northern sector by the German 164th light infantry Division, the Italian 102nd Trento Infantry Division, the 7th Bersaglieri regiment, and the 25th Bologna Infantry Division. In reserve were deployed the 133rd Littorio Armored Division, the 101st Trieste Motorized Division, the 15th Panzer Division, and the German 90th light Infantry Division. The 27th Brescia Infantry Division, the Ramcke Fallschirmjäger Brigade, the elite 185th Folgore Airborne Division, guarded the southern sector. Finally, the 17th Pavia Infantry Division positioned itself in the proximity of the Qattara Depression. The 132nd Ariete Armored Division and the 21st Panzer Division awaited in reserve.

Deployment of forces on the eve of the Battle of El Alamein.

Before the battle, the balance of force between the two sides was extremely uneven, 195,000 allied troops with 1,000 tanks and 2,000 guns of all types against 116,000 Axis troops with 547 tanks and 1,000 guns. The Allied arsenal was superior in all levels, from tanks to artillery, as well as the uncontested air superiority of the Western Desert Air Force.

Operation Lightfoot

On the evening of 23 October 1942, Operation “Lightfoot” began. About 1,000 artillery pieces of the 8th Army fired on the Axis positions, unleashing hell for 15 minutes. After this general bombardment, guns trained on designated targets and kept firing for several hours. In the meantime, The British infantry moved forward and began opening gaps in the minefields. Securing these gaps would create a safe passage for the armored units. The attack was launched on a broad front, involving the sectors guarded by the Trento, Bologna, and 164th Division in the north, Folgore, and Pavia in the south.

Allied progress slowed by the underestimated vastness of the minefields. The slow pace prevented their ability to exploit their numerical superiority fully.

Battle Begins

Fierce fighting erupted on the first night. The Folgore Division, attacked by elements of the 7th British armored Division and 44th infantry Division, stood its ground, repealing the initial assault and destroying 30 tanks with Molotov-cocktails. In the northern sector, three British divisions slowly advanced, creating a small bulge between the Trento and 164th infantry Division positions. They made their way near to Hill 28, a key position known to the British as Kidney ridge.

Italian tanks preparing to engage Allied forces in North Africa.

24 October 1942 saw the first Axis counterattack against Allied forces in the bulge east of Kidney ridge. The 15th Panzer and Littorio Division attacked the British 1st armored Division. The clash destroyed roughly 50 tanks, and the Axis failed to push back the enemy.

On the 25th, the Folgore Division saw new attacks carried by the 7th Armored Division. The paratroopers once again fought with bravery and determination. Near Deir El Mussaib, 250 men of the Folgore repealed 1,500 enemies advancing forward. Meanwhile, in the north, clashes between armored units continued to unfold near Kidney ridge. Fighting continued in the coastal area between Bersaglieri and Australians, and around the Bulge between the Trento, the 164th Division and Commonwealth units. Both sides suffered heavy casualties.

Rommel Returns

That same day Rommel returned and resumed command. The previous day General Stumme died of a heart attack in the early hours of the battle. Although the frontline held, he assessed the decreasing fuel reserves would limit the deployment of Axis tank. His combat units, especially armor, continued to weaken due to battle attrition.

On the 26th, the allied offensive effectively stalled. Montgomery decided to concentrate his attention on the northern sector since the south showed no progress. Rommel realized this and moved the 21st Panzer north to reinforce the Littorio and 15th Panzer Division, the latter having only 30 operational tanks. At this point, Rommel’s armor consisted of 187 M13 and M14 and 121 Panzer III and IV. The Trento Division lost all its artillery and operated at half strength. The Allies wiped also wiped out two battalions of the 164th Division.

On the morning of 27 October 1942, Sherman tanks of the 1st Armored Division repealed a Littorio Division attack. The little M13 and M14 were no match against the American-made new medium tanks. Attacks and counterattacks in the area of Kidney ridge continued without pause in the following days. Meanwhile, the 8th army began amassing its armor for a final assault. Assessing the dire situation, Rommel began considering a retreat to redeployed his forces back to Fuka.

Operation Supercharge

In the early hours of 2 November 1942, Montogomery launched his Supercharge, the final push to destroy the Italo-German army at El Alamein. The Australians advanced in the coastal area, pushing back the 90th light German Division. The 2nd New Zealanders Division and the British 1st Armored Division attacked the positions held by the Trieste and the 164th Infantry Divisions. The massive assault pushed back the Axis infantry.

An M13/40 in North Africa in 1942. Image: Public domain.

A counterattack of the 15th, 21th Panzer and Littorio in the area of Tel El Aqqaqir began at around 0900 hours. The battle included 120 axis tanks against 300 allied tanks. Upon its conclusion, only 24 Panzers and 17 M13/40 and M14/41 remained operational in the sector, and the Allies made headway.

Axis Retreat and Allied Breakout

In the afternoon, Rommel ordered the retreat of all Axis units and recalled the Ariete north to cover the retreat. At this point, the Ariete remained the only mostly intact armored unit at Rommel’s disposal, counting around 100-120 tanks. Between 2 – 3 November, Italian infantry managed to complete the retreat on foot to their new positions. On the way, they abandoned all heavy equipment. They were previously towing the 47mm light AT guns by hand.

The “fighting retreat,” as envisaged by Rommel, began, and a complete disengagement seemed possible. However, on 3 November, Rommel received the infamous order from Hitler to halt the retreat and fight until “victory or death.” Reluctantly, Rommel obeyed and ordered his unit to stop the retreat, already in motion, which added additional chaos to the volatile situation. However, not all axis units received this last order. So most of them continued the retreat. The definitive retreat order subsequently came on the 4th.

On the morning of 4 November, the final offensive of the 8th army started. Its objective was to destroy the remaining Axis armored units and capture the retreating infantry.

Last stand of the Ariete

The Ariete Division arrived in the northern sector on 3 November 1942. They received orders, together with the remnants of Littorio, and Trieste, to delay the enemy’s advance in the attempt to cover the retreat of the Axis army. The Division reached Bir el Abd, southwest of Kidney ridge, and assumed defensive positions. It subsequently deployed its IX, X and XIII tank battalions forward, followed by Bersaglieri, artillery and AT guns.

Churchill III tanks of the 1st Armored Division on 5 November 1942. Image: Public domain.

At 8:30 on 4 November, the Ariete sighted the approaching tanks of the British 7th Armored Division. The X battalion charged the enemy in a frontal assault, which was soon repealed by the enemy. The Italian tanks withdrew. However, the British did not immediately come forward, fearing an ambush from the AT guns of the Ariete. At 10:30, they completed their final refueling in preparation for the next British attack. Tanks, AT guns, SPGs and Bersaglieri fought relentlessly for the entire morning, at 15:30 Rommel received one last message from the Ariete which red:

“Enemy tanks broke through south of Ariete Division. Thus, Ariete surrounded, located 5 kilometers north-west of Bir-el-Abd. Ariete tanks are fighting.”

What happened afterward is not entirely clear. What is sure is that most of the Ariete Division became annihilated in the uneven fight. In the late afternoon came the news that some tanks of the XIII tank battalion with 200 Bersaglieri managed to escape and retreated to Fuka. However, there they would have been wiped out by the advancing 8th army.

Aftermath

The remnants of the 4 German divisions managed to disengage and retreat towards Libya. But not so for the Italian divisions, who did not possess vehicles or transports of any sort. They fought while retreating until exhaustion or running out of ammunition. During the retreat, the Bologna, Trento, Pavia, and Brescia Infantry Divisions ceased to exist as combat units. The Littorio and Ariete also were destroyed. Only elements of the Trieste managed to retreat and fight until the Axis surrender in Tunisia.

German prisoners under a sign for El Alamein.

Lagging behind, the Folgore Division continued fighting relentlessly during the withdrawal. They refused every offer of surrender advanced by the British. On 6 November 1942, after depleting their ammunition supply, General Frattini surrendered his last men to the 44th Highlander Division. They paid tribute to the Folgore with full military honors. Out of 5,000 paratroopers, only 304 survived.

The Battle of El Alamein ended on 11 November 1942. It cost the Allies 13,560 dead and wounded while 300-500 tanks destroyed. Variation exists due to sources and classifications. On the Axis side, numbers are more uncertain. A consensus lists 35,000 men captured, 15,000 wounded, and between 9,000-12,000 dead. The Second Battle of El Alamein destroyed about 500 Axis tanks.

Sources

Rebora, A., Carri Ariete Combattono, Prospettiva Editrice (2016)

Petacco, A., L’armata nel deserto, Mondadori (2001)

Campini, D., Ferrea Mole Ferreo Cuore, Solidershop (2015)

Jowett, P., L’esercito italiano nella Seconda guerra mondiale, LEG edizioni (2019)