The main thrust of the Italian invasion of France occurred on 21 June 1940. The conflict would last until 25 June following the French armistice signed on the 24th. Many historians question the motive for Mussolini to attack France as Germany overran the country. One suggested theory is that Mussolini feared a German/French conspiracy in targeting Italy as its next victim. According to this theory, Mussolini’s goal was to create an impenetrable border between France and Italy to prevent an attack from the western Alps.

I only need a few thousand dead so that I can sit at the peace conference as a man who has fought.

According to many historians, this was Benito Mussolini‘s phrase that generated the Italian attack on France (13-24 June 1940). It was the first Italian military operation in World War Two, and one of the most criticized of the whole war.

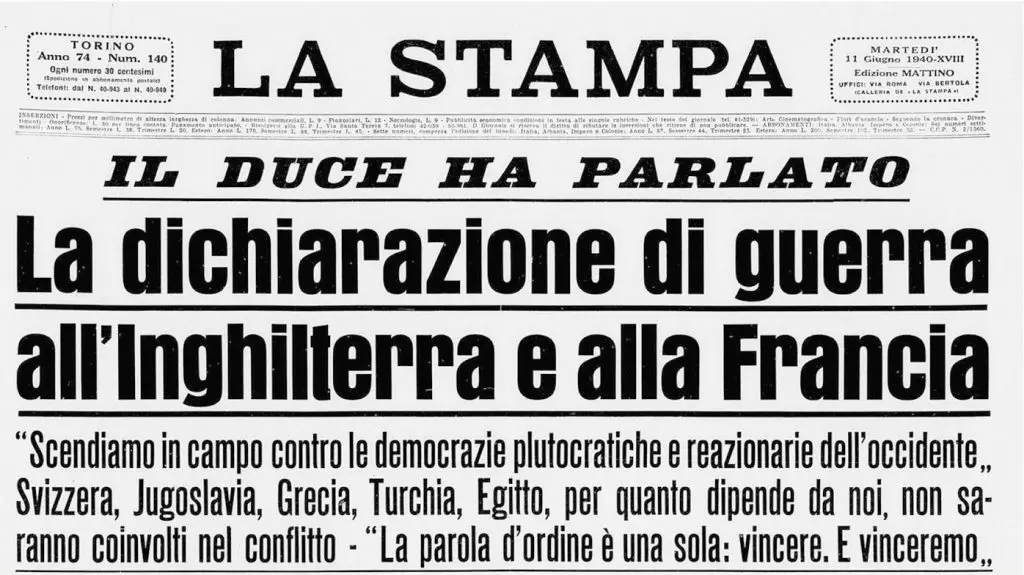

The 11 June 1940 headline of the newspaper “La Stampa” stating the declaration of war against England and France.

Indeed, Mussolini ordered the attack after seeing the brilliant results Germany obtained in the French campaign. Hoping to gain as many benefits as possible from the truce, Mussolini jumped on the German bandwagon as France’s defeat seemed imminent.

For this reason, the attack of France was considered by many observers as a very dishonorable action. Italy became defined as the nation that “stabbed the neighbor’s back” ( F.D. Roosevelt) or which “killed a dying man” (G. Salvemini).

This interpretation of the facts has a partial truth. However, accurate analysis of the military and political aspects of the operation reveals a scenery hidden from view. The Italian invasion of France requires a more extensive and complex explanation.

The Conflict Begins

The invasion of France started two days following the Italian declaration of war on 10 June 1940. During the night between the 12th and the 13th of June, Italian bomber squadrons attacked southern France. They hit two small towns, Hyeres and St. Raphael, and the Naval base in Toulon. Additionally, the Regia Aeronautica bombed Bastia and Calvi on Corsica and Bizerte in Tunisia.

The French responded with their Navy on the morning of 14 June. The 3rd Cruiser Squadron, under the command of Admiral Emile Duplat, bombed the fuel depot of Vado Ligure and the harbor of Genoa. The squadron was composed of 4 cruisers Algerie, Foch, Dupleix, Colbert, and 11 destroyers. The French achieved minimal success due to Italian coastal batteries and naval unit reprisals.

During the bombing of Genoa, one of the French destroyers, Albatros, was hit by a 152 mm coastal battery shell as well as a torpedo from the escort vessel “Calatafimi.” The damaged ship reported ten crewmen killed, and the squadron returned to base.

The Front

On 20 June, the land operation against France, aptly named the “Battle of the Alps,” commenced. The declared target of the Italian attack was Nice and Savoy. These ex-Italian territories were yielded to Napoleon III by Cavour after the Plombières Accords of 1858.

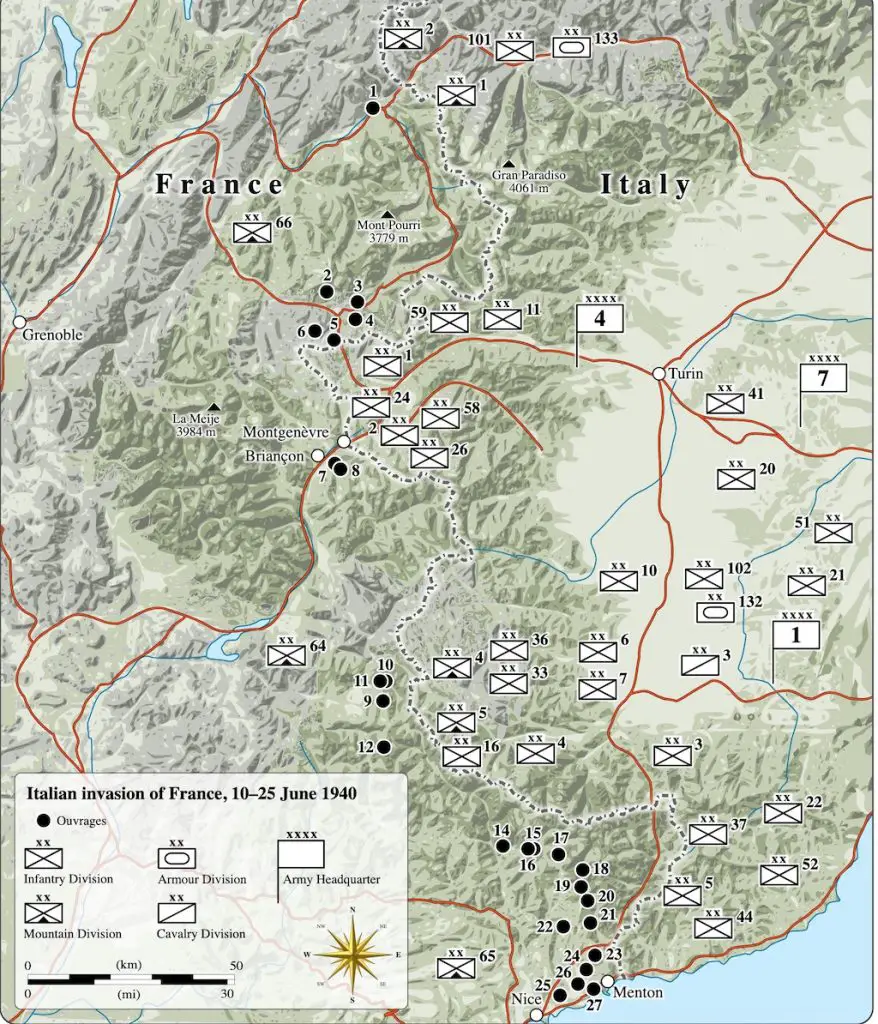

The French/Italian Front. Image: Goran tek-en / CC BY-SA 4.0

The front covered a 520 km long border between Italy and France that included the Western Alps mountain range from Monte Dolent near Switzerland to the sea. The front included an impervious mountain territory with an average altitude of 2500 meters and dotted with fortifications by both countries.

Historically, Italy planned for a French invasion. Italy never considered invading France because the area contained three parallel rows of mountains along its borderline with no targets of value immediately behind them. Alternatively, Italy possessed only one row of mountains and many viable targets in the vicinity. Carl von Clausewitz said: “Attacking France from the Alps is just like try to lift a rifle by grabbing it from the tip of its bayonet.”

Along its border with Italy, France had a system of modern fortifications called “The Alpine Maginot’s Line.” Italy also had its fortification system called “The Alpine Wall.”

To execute its attack, Italy deployed two armies. The first included the IV° Armata under the command of General Alfredo Guzzoni between Monte Dolent to Monte Granero. The second was the I° Armata under the command of General Pietro Pintor, from Monte Granero to the sea.

Italy had a total of 22 divisions equivalent to 300,000 men, and 2,900 cannons of various caliber and the “Alpine Wall” garrisons.

Related: Invasion of France Order of Battle 20 June 1940

Under the command of General Renè Orly, the French deployed the “Armeè des Alpes” which had yet to reposition itself to the German front. In fact, of the 550,000 soldiers deployed along the borderline in September 1939, only 150,000 were present in the same zone in June 1940. The French forces included 70 platoons of “èclaireurs-skieurs” (mountain scout-skier troops) plus the Alpine Maginot’s garrisons for a total amount of circa 180,000 men.

Invasion of France

The main offensive started on the morning of 21 June. Both Italian armies received the same order: The advanced troops, mostly “Alpini” brigades, must break through the French line and create as many passages as possible. They then must take possession of the strategic peaks. Other troops will descend into the French valleys to begin occupation. Some of these troops will attack the French line at the back.

Italian First Army in the invasion of France. Image credit: Goran tek-en [CC BY-SA 4.0]

The second day included another massive offensive all along the front, which seemed to be slightly more penetrating than the previous one. The Italian pressure against the French line increased. Near the Isere Valley, Italian troops bypassed the defenses and began the occupation of the valley. On the same day along the coastal front, armored trains continued bombing without a measurable result. Later, French shells practically destroyed one of the three trains. This attack also killed the train commander G. Ingrao and eight crewmen.

The Val Dora battalion of the 5th Alpini Regiment in action in the Colle della Pelouse during the Italian invasion of France in June 1940. Image: L’illustrazione Italiana (19 July 1942).

Although the battle seemed to turn in Italy’s favor, the French line resisted the attack. On the morning of 23 June, French forces began heavy artillery fire all along the front. It practically stopped Italian advances. Italian artillery responded, and the battle became static artillery engagements. However, Italian troops soon occupied the fort of Chenaillet. The French army retreated from the Trois Tetes fort, but the Italians made minimal progress. French troops resisted, and they did it well.

The fourth day of battle seemed to be a copy of the previous one with a violent exchange of artillery shells until that afternoon. French artillery appeared to gradually decrease fire. This change of momentum surprised many Italian officers. Italian units avoided an advance fearing an ambush. However, by the late evening, an Italian command received a dispatch order to cease operations because France capitulated to Italy.

In effect, at 1915 hours of 24 June, a French delegation signed the armistice with Italy at Villa Incisa, in Rome. The Italian delegation chief was Marshal Pietro Badoglio.

Results of the Battle of the Alps

The truce concluded the “Battle of the Alps,” a four-day battle that did not have a clear military winner. An objective analysis must reveal that the French army won. Indeed, at the end of the conflict, the Italian army penetrated only a few kilometers into the French territory. Additionally, Italian forces were unable to bypass the French defensive line. A line that appeared able to resist for many weeks or months to come.

The four-day war demonstrated that the attempted Italian invasion of France from the Alps was a prohibitive task. The Italian army reported 642 killed, 616 missing, 2,631 wounded, 2,151 frostbitten, and 1,141 prisoners (set free immediately after the armistice). The French Army reported 32 Killed, 121 wounded, and 259 prisoners.

Some historians believe the disproportionate numbers is due to the lack of training and equipment of the Italian troops. However, the rough terrain and strategic positioning of the French fortifications may have played a considerable role in the French victory.

Three hundred years of European military strategy show that invading France from the Alps as an impossible task. The Battle of the Alps was the practical confirmation of this theoretical rule.

Franco-Italian Armistice

Many historians agree that Italy declared war on France to gain easy war concessions. But according to the armistice’s clauses, this assertion doesn’t seem to be true.

Italy imposed these conditions on France:

- The creation of a 50 km wide demilitarized zone on the Italian/French border as well as between Libya/Tunisia.

- The demilitarization of French Somalia.

- The use of Djibouti’s harbor.

- The use of the Addis Ababa-Djibouti railway.

Even if the fascist propaganda talked about a brilliant victory and a huge booty, the actual Italian gains were minimal. In fact, the concessions are almost ridiculous. In essence, it consisted of 832 km² of territory. It contained no industries, no significant infrastructure or rails, and no productive lands. The only significant city was Menton, a charming tourist town on the French coast. Considering that the Italian army employed 10 Divisions in this conflict, we can easily see the costs outweighed the benefits.

Italian troops occupying the French town of Menton. Image: Public Domain.

Mussolini personally decided on the list of concessions. The Duce’s staff had previously prepared the first draft with more substantial clauses. But in the end, Mussolini opted for a personal list.

It is generally believed the mild concessions requested stemmed from Mussolini’s “sportsmanship.” That is, he understood Italy did not achieve a significant victory which entitled large acquisitions. American History writer Samuel W. Mitcham believes Hitler did not feel Italy should be rewarded for its poor performance in the invasion. He, therefore, convinced Mussolini to request much less than what Italy originally wanted. However, this does not explain Hitler’s later suggestion for Italy should occupy the additional border area between France and Switzerland. According to MacGregor Knox in his book The Sources of Italy’s Defeat in 1940: Bluff or Institutionalized Incompetence, Fascist diplomat Dino Alfieri, believed Mussolini attempted to maintain some semblance of a balance of power in Europe.

Since Italy clearly did not request large territories, another theory has been suggested regarding Italy’s invasion of France.

Preventing a German – French Attack Theory

A plausible theory is that Italy attacked France for a matter of preventive defense. During that period, Mussolini strongly feared that after France’s defeat, Germany’s next victim would be Italy. Mussolini and his fascist establishment saw the rapid German advance into France as suspicious.

They most likely suspected France and Germany reached a secret accord for a quick capitulation as the prelude of a new phase of the Axis. This new phase included a collaborationist France as Germany’s favorite ally. France was the natural enemy of fascist Italy. Mussolini feared a renewed Axis in which an allied France and Germany annihilate Italy.

Mussolini’s suspicion of a French-German plot most likely increased when Marshall Philippe Petain became designated as the new French Premier in the first days of June 1940. Witnessing this event, Mussolini and some of his collaborators decided not to delay a military action aimed to increase the defensive power of Italy.

The Italian aims on the western Alps can be understood using this logic. Italian possession of the whole mountain range would make Italy practically impenetrable through France. Germany would avoid the risk of reliving the hard times they experienced on the eastern front in WW1 by attacking the western Alps.

As a further confirmation of this theory, as Italy attacked France, Mussolini ordered a reinforcement of the eastern Alps fortifications along the borderline between Italy and the annexed German Austria.

The theory of a “preventative defense war” also explains why the 24 June armistice included so little for Italy. Indeed, by a strategic point of view, a more significant request of territory would require a larger number of army divisions to defend. If an attack occurred, the divisions deployed far from the border would be easily cut off and captured by the enemy.

For the same reason, a couple of months after the Villa Incisa’s armistice, Mussolini refused Hitler’s proposal to extend the Italian zone all along the border between France and Switzerland.

Even if a definitive confirmation of this theory remains elusive, Italian confidential reports and lesser-known documents seem to reference the suspected French-German plot. For example, a short passage of Mussolini’s speech at the Italian Ministers Council dated 5 July 1940 reveals many of the suspicions he had with France and Germany.

We must be careful with France, which now is preparing a trick to ask the Axis membership card. We shouldn’t be surprised. I have alerted our German friends who were almost moved by the losers. Losers, but how were they beaten? When the crust broke, the Germans marched like a blade into the butter. Take a look at their war movies. The Germans had no casualties.

Conclusion

The Italian invasion of France reveals how the Axis was far from being what it represents with its propaganda of a “Pact of Steel.” Nobody should be surprised that these things happened at the same time in which Mussolini’s public speeches were in favor of Germany.

Indeed, the dualism and the double strategy were constant in the political career of the Italian dictator. Despite his representation, Mussolini was a mercurial man, reflective but often unsure and suspicious. He always had the habit of changing course at the last moment, sometimes greatly surprising his staff as it happened.

If, by a political point of view, these attitudes made Mussolini’s fortune in times of peace, surely they had a decisive effect on his luck in wartime. A time where facts are more important than the words, and there is no time for late afterthoughts.

History shows that after the attack on France, the Axis evolved in a different way than Mussolini expected. And the real risk of an invasion of Italy in June 1940 is yet to be known.

What is certain is the sacrifice of hundreds of men who gave their lives in a small, but also dark, operation of the Italian war—and a prelude to many more significant tragedies.