Refuting the lingering legacy of Allied propaganda in the Second World War

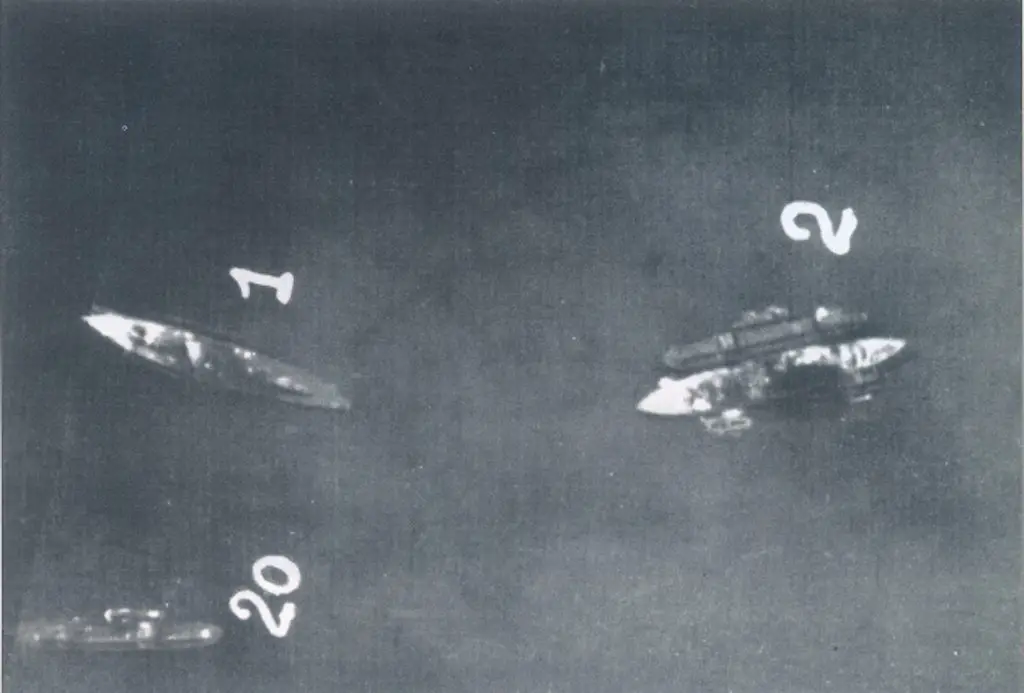

After hearing that teams of Italian frogmen had sunk the only two British battleships left in the Mediterranean in December of 1941, British Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham stated, “We are having shock after shock out here. The damage to the battleships at this time is a disaster. One cannot but admire the cold-blooded bravery and enterprise of these Italians.”

The sinking of those battleships altered the strategic scenario in the Mediterranean theater for the next year of the war, but you will read about this example of Italian courage and ingenuity or others like it in precious few American history books on the Second World War. Instead, in these books, you will no doubt see the inevitable photo of Italian soldiers surrendering en masse.

Big Lie

It is somewhat ironic that the “Big Lie” technique first elaborated by Adolf Hitler in Mein Kampf was used so effectively by Hitler’s adversaries to brand his Italian allies as hapless cowards in World War II. More than 70 years after the fact, the Italian military’s reputation has still not recovered from the successful implementation of the “Big Lie” in Allied propaganda.

In Mein Kampf, Hitler states that people “more readily fall victims to the big lie than the small lie, since they themselves often tell small lies in little matters but would be ashamed to resort to large-scale falsehoods. It would never come into their heads to fabricate colossal untruths and they would not believe that others could have the impudence to distort the truth so infamously.”

The big lies about the Italian military in the Second World War are that they would not fight and were inept; they lacked courage and were terrible soldiers. The lies have their origins in the British wartime propaganda of the early 1940s.

For the purpose of raising domestic morale, the Italian enemy was ridiculed and denigrated, especially after an initial British victory over the Italians in the deserts of North Africa. The fact that the British would employ such a technique in wartime to assuage their population is understandable. However, the fact that three subsequent generations of American military historians have bought into these big lies and continue to promulgate them in print is regrettable.

It does a great disservice to actual history and manifests certain scholarly laziness. For anyone who does even a small modicum of real research on the Italian military in the Second World War, you will discover that the truth of their performance is far different than the prevailing stereotypes suggest.

Folgore

Proof is often found in the words of the adversaries who fought against the Italians and the allies that fought with them. For example, after the heroic Folgore division of paratroopers destroyed over 120 British tanks, and saw their numbers decimated from 5,000 to 306 as they covered the Axis retreat in the desert battle of El Alamein, British General Hughes, who led the opposing British 44th infantry division stated, “I wish to say that in all my life, I have never encountered soldiers like those of the Folgore.”

No less an adversary than Winston Churchill himself praised the Folgore when, before Parliament on November 21, 1942, he said, “We really must bow in front of the rest of those who have been the “lions” of the Folgore Division.”

Bersaglieri

Meanwhile, Erwin Rommel, the famous “Desert Fox” whose forces in North Africa always included a preponderance of Italians, said of the Bersaglieri, elite Italian light infantry formations, “The German soldier has impressed the world. However, the Italian Bersaglieri has impressed the German soldier.”

It is an indisputable fact that many Axis victories in North Africa attributed simply to the “genius of Rommel” were won with the blood and valor of the Italians, not the least of which was the battle of Tobruk in Libya when on June 21, 1942, the British surrendered the famous garrison along with 33,000 prisoners to General Navarrini commanding a numerically inferior Italian force of only 30,000.

In Knights Cross: A Life of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, author David Fraser puts all this in perspective when he states by late 1941 “several enemy (British) reports credited Italian infantry with fighting exceptionally hard-on occasion-harder than their German comrades.”

East Africa Campaign

Italian heroism was hardly confined to the North African theater. In East Africa, despite having their supplies cut off with the closing of the Suez Canal, the Italians fought tenaciously in battles such as Agordat and Keren in Eritrea. Italian cavalry officer Amadeo Guillet, nicknamed the “Devil Commander” by the British, tried to slow the inevitable British advance in East Africa by hurling his cavalry against a British armored unit in what was to be the last cavalry charge ever faced by the British military.

According to a contemporary account of the event in the British newspaper The Observer, “Yelling, flashing scimitars, firing carbines and tossing grenades, the 1,500 Italian horsemen swept through the camp, attacking tank crews and brigade HQ staff in a whirlwind of dust and gunfire.”

When Guillet’s biography was published in 2003, Martin Boot of the London Sunday Times opined, “This book lays to rest the Italian reputation for military incompetence and lack of valor. Instead we can only marvel at the bravery of Amadeo.”

Savoia Cavalry

A year after Amadeo Guillet’s cavalry charged successfully through British armor, his friend and fellow cavalry officer, Colonel Alessandro Bettoni, was preparing to launch another daring cavalry charge against a superior Russian force on the banks of the Don River.

This would be the last cavalry charge in recorded history, and it resulted in another resounding Italian victory. On the morning of August 24, 1942, the 600 men of the Savoia Cavalry regiment, who were part of the Italian Expeditionary Corps fighting alongside the Germans on the Russian front, mounted their horses and upon the traditional cry of Avanti Savoia! (Forward Savoy!) they unsheathed their sabers and charged a Russian position comprised of 2,000 men equipped with artillery and mortar support.

Within a couple of hours, the battle was over. The Italians had wiped out two Russian battalions and sent a third packing across the Don, leaving behind 500 prisoners.

Despite these remarkable facts, and others too numerous to mention, the vast majority of American written histories of World War II have bought into the Big Lie of the poor fighting quality of the Italian military.

It Begins With Operation Compass

This initially sprang from “Operation Compass” when in 1940, a numerically superior Italian army that had advanced from Libya into Egypt, under direct orders from Mussolini but against the will of the army’s commander General Rudolfo Graziani, was routed by a much smaller British force, yet one that was vastly superior in vehicles and armor, which are the keys to success in a desert war.

As General Graziani later famously stated, “In this theater of operations a single armored division is more important than an entire (infantry) army.” As a result of Mussolini’s reckless decision, 115,000 Italians were taken prisoner in “Operation Compass,” and the stigma of Italian cowardice in World War II had begun.

The British took full propaganda advantage of this victory, and soon Hollywood followed suit, churning out wartime movies like Five Graves to Cairo, Sahara and Casablanca which made the Italians look like buffoons and bunglers-a trend which continues in American World War II themed movies to this day.

Why the Italians were the only ones stigmatized in such a manner, when the British themselves suffered a number of similar military catastrophes, including the Fall of Singapore in which they surrendered a numerically superior and better provisioned force of nearly 80,000 to the Japanese, has a lot to say about the validity of the old adage that history is written by the victors.

In 2004, during one of his last interviews, the late professor Gunther Rothenberg, who was one of the world authorities in military history and also a veteran of the British 8th army who fought against the Italians in World War II, stated that the Italian troops had been “as good as any other on both sides” and acknowledged their subsequent reputation was based on “just propaganda.”

An Objective Analysis

The simple fact is that Italy was never properly prepared to fight in World War II. Its armories had been depleted by the Ethiopian War and the Spanish Civil War, and it lacked the natural resources and industrial capacity to compete with its adversaries.

But as the famous British historian, Hugh Seton-Watson observed, “Italy had two choices before it: either to throw in with Germany in order to become a large, powerful empire at the expense of Britain and France, or to join the two Western Powers against Germany and eke out a middling existence as a weak insignificant country.”

In June 1940, when Italy declared war on England and France, it looked as though a German victory was assured. Mussolini thought he could gain his share of the spoils for Italy without committing it to a long war that it could ill-afford. It was a fatal miscalculation. Hundreds of thousands of Italian soldiers trudged off to battle, many of them on foot, with inadequate supplies and antiquated or ill-suited weapons that were little match against Allied troops.

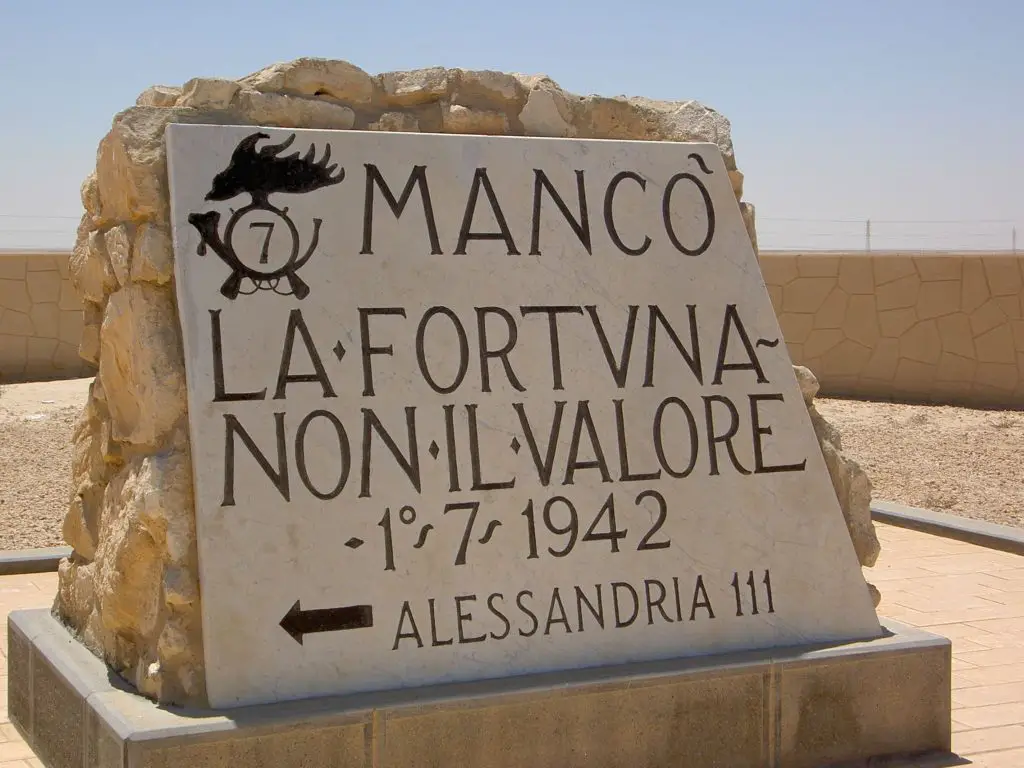

Despite these shortcomings, as has been demonstrated, the Italians were capable of fighting hard for the honor of their country despite the reservations that many of them had for the rationale of the war. Perhaps the most fitting tribute to the Italian military is written on a humble marker that lies three miles west of El Alamein in Egypt, where so many of them gave their lives. The marker, erected by Italian soldiers, represents the furthest point east that the Italian army advanced in the desert campaign. It reads simply, “Manco la fortuna non il valore“-Fortune was lacking, not valor.